Did

you know that Queen Anne’s Lace, that pretty little white flower, growing innocently

in the field, has some dangerous cousins?

Well, it does!

Queen

Anne's Lace, daucus carota, is a biennial

plant that is native to Europe and southwest Asia, and which can grow to 3feet

(1 m) in height. It is a member of the

carrot family, Apiaceae, also known as Umbelliferae, that was

brought to North America by European settlers.

But it can cause allergic reactions in those with sensitive skin, and it

shares a family membership with the Wild Parnsip, pastinaca

sativa, and with Poison Hemlock,

conium maculatum L.

Dangerous

cousins...

Poison hemlock and wild

parsnip both belong to the carrot family, and both are very dangerous to humans,

but in very different ways.

Poison hemlock, Socrates?

Poison hemlock is often called the “deadliest plant in America”, and all parts of the plant are poisonous. According to the USDA, theplant contains highly toxic piperidine alkaloid compounds, including coniine and gamma-coniceine, which cause respiratory paralysis4 and death in mammals. Poison hemlock, conium maculatum, is the plant that was used to kill the Greek statesmen Theramenes, Polemarchus, Phocion and Socrates, and the Greek genus name Conium means to spin or whirl, referring to the symptoms of hemlock poisoning.

Poison hemlock toxins to cause poisoning must either be ingested or enter the body by some other means. Poison hemlock sap on your sap skin can allow toxins to enter your body through your eyes, or from the improper handling of food. Poison hemlock sap on your skin does not cause skin blistering.

Accidental inhalation through nasal passages, if burning the plants, is also a concern. Unlike other members of its family, poison hemlock sap does not cause skin blistering and photodermatitis.

Poison

hemlock plants have hairless stems, which are

covered with an epicuticular wax that gives the stems a blueish-green color and

are covered in purplish blotches. They

have parsley or carrot-like leaves and an umbrella like spray of white flowers. Mature poison hemlock plants can measure between

6 and 10 feet (1.8 to 3 meters) tall.

Wild parsnip ... don’t eat!

Wild parsnip contains furanocoumarins, just

like other members of the Apiaceae family like giant hogweed, cow parsnip, (for

more go HERE

and HERE)

parsley, celery, carrots, and these furanocoumarins react using their parent

compound, psoralen, when activated by sunlight’s UV rays.

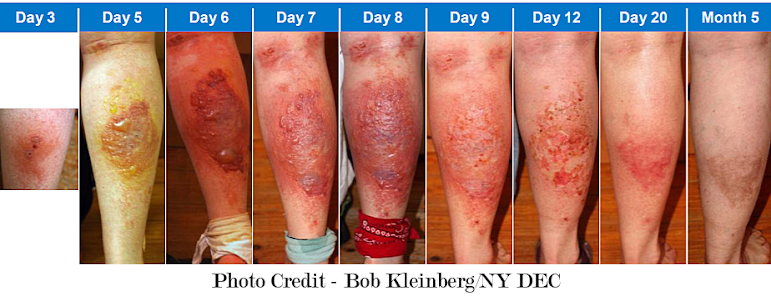

Wild

parsnip sap causes severe phytophotodermatitis or skin blistering, when your

skin is exposed to sunlight and UV radiation,

Phytophotodermatitis is not an immunologic response, and the symptoms typically

begins within 24 hours of exposure and peak 48 to 72 hours after exposure. At the

outset, your skin turns red and starts to itch and burn. Large blisters will form within 48 hours. The blisters sometimes leave black, brown, or

purplish scars that can last for several years. This hyperpigmentation of the scars is caused

by the production of melanin caused by the furanocoumarins. The disconnect between the first onset of

symptoms can result in blaming other plants for the blisters.

For

more information about wild parsnip burns go HERE

and HERE.

Both

wild parnsip and poison hemlock are often found along roadsides, frequently

mixed together.

So,

watch out while you are out and about and stay away from that not so innocent

flower, queen anne’s lace, dangerous cousins!

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and look for me

on YouTube at BandanaMan Productions for other related videos, HERE. Don’t forget to follow me on both The

Woodsman’s Journal Online, HERE,

and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube. If you have questions, as always, feel free

to leave a comment on either site. I

announce new articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds, on Instagram at

bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch for me.

That

is all for now, and as always, until next time, Happy Trails!

Sources

Boggs,

Joe; “Poison Hemlock and Wild Parsnip: TOO LATE!”, May 23, 2024, [© 2016, The

Ohio State University], https://bygl.osu.edu/node/2356,

accessed July 27, 2024

Calvert, Ryan; “Native Plants of Arizona 2004: Conium

maculatum L.”, https://web.archive.org/web/20120623113546/http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/plants-c/bio414/species%20pages/conium%20maculatum.htm,

accessed July 27, 2024

McMahon,

Meghan; “Know the nasties”, July 2, 2019, [© 2024

The Forest Preserve District of Will County], https://www.reconnectwithnature.org/news-events/big-features/know-the-nasties/,

accessed July 27, 2024

New

York Invasive Species Information; “Giant Hogweed”, [© New

York Invasive Species Information 2024],

https://nyis.info/invasive_species/giant-hogweed/,

accessed June 15, 2024

Polly, “Steer Clear of

Dangerous Plant That Causes Painful Burns & Permanent Scars”, [© 2024 Big

Frog 104, Townsquare Media, Inc], https://bigfrog104.com/steer-clear-of-dangerous-plant-that-causes-painful-burns-permanent-scars/?utm_source=tsmclip&utm_medium=referral,

accessed June 14, 2024

USDA, “Conium maculatum

L., poison hemlock”, https://plants.usda.gov/home/plantProfile?symbol=COMA2,

accessed July 25, 2024

USDA,

“Daucus carota L. var. carota, Queen Anne's lace”, https://plants.usda.gov/home/plantProfile?symbol=DACA6,

accessed July 25, 2024

USDA,

“Pastinaca sativa L., wild parsnip”, https://plants.usda.gov/home/plantProfile?symbol=PASA2,

accessed July 25, 2024

USDA,

“Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum)”, June 26, 2018, https://www.ars.usda.gov/pacific-west-area/logan-ut/poisonous-plant-research/docs/poison-hemlock-conium-maculatum,

accessed July 27, 2024

Wikimedia; The Death

of Socrates, Jacques-Louis David

(1748–1825), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:David_-_The_Death_of_Socrates.jpg,

accessed July 27, 2024

%20trimmed.jpg)

%20trimmed.jpg)