Forest

fires, wildfires, brushfires, conflagrations, infernos, global cataclysms! It doesn’t matter what you called them, but it

seems like everyone was talking about them on June 7th, as the smoke

from the Canadian wildfires drifted down the East Coast of the United States,

negatively effecting air quality on a continental scale.

This

week we will talk about what causes a wildfire to become an inferno, and next

week we will talk about how to survive a wildfire in the

wilderness, if you get caught up in one!

Wildfire!

What turns an ordinary small and controllable flame into an uncontrollable inferno?

Wildfires,

just like small campfires, need three ingredients to sustain combustion; fuel,

oxygen, and heat source to ignite the fuel.

The heat from a wildfire is radiated, conducted, or transferred by

convention to other nearby fuels and the fire grows and grows.

Besides

fuel, there are two other conditions, weather, and topography, which when

combined change a controllable fire into a monster conflagration, out of

control.

Fuel

Wildfire

fuels are typically the remains of plants, however the quality of the fuel, its

ability to easily combust, depends on its surface area and the amount of

moisture that it has absorbed from the environment around it.

The smaller and finer the fuel, the easier it catches fire and the faster it burns, because of its greater surface, than larger, thicker fuel.

moisture from the environment. When the moisture content of the fuel is high, it is difficult to ignite, and it will burn poorly, if at all. When moisture in the fuel is low, it will ignite quickly, and will burn well.

Topography

Topography,

the shape of the land’s surface, has a major effect on how fast a fire moves and where it moves to. Fires run

uphill surprisingly fast, particularly on steep slopes, and in gullies, which

funnel the wind.

Don’t forget to come back next week and read “Surviving a Wildfire!

Part One©”, where we will talk about how

to survive a wildfire in the wilderness if you get caught up in one!

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and look for me

on YouTube at BandanaMan Productions for other related videos, HERE. Don’t forget to follow me on both The

Woodsman’s Journal Online, HERE,

and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube. If you have questions, as always, feel free

to leave a comment on either site. I

announce new articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds, on Instagram at

bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch for me.

That

is all for now, and as always, until next time, Happy Trails!

Sources

Countryman, Clive M.; Heat-Its

Role in Wildland Fire- Part 1, [U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest

Service, Pacific Northwest, 1975], https://books.google.com/books?id=9-4TAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Fuels+for+Radiation+and+Wildland+Fire&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiH_eO1vsH_AhVSFVkFHXwmAuQQ6AF6BAgDEAI#v=onepage&q=Fuels%20for%20Radiation%20and%20Wildland%20Fire&f=false,

accessed June 13, 2023

Schroeder, Mark J., and

Buck, Charles C.; Fire Weather: Agricultural Handbook 360, [U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Broomall, PA, May 1970], https://books.google.com/books?id=j4f_lBHsSKEC&pg=PA88-IA2&dq=%22smoke+columns%22+wind+direction&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjI6r_dzsH_AhX4EWIAHYqwCwgQ6AF6BAgHEAI#v=onepage&q=%22smoke%20columns%22%20wind%20direction&f=false,

accessed June 13, 2023

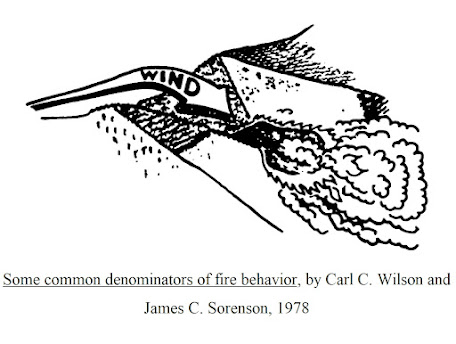

Wilson, Carl C., and

Sorenson, James C.; Some common denominators of fire behavior, [U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Broomall,

PA, December 1978], https://books.google.com/books?id=w_tq7y2v8I4C&printsec=frontcover&dq=smoke+wind+direction+wildfire&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi78oTswcH_AhUxMVkFHSE_Dd04ChDoAXoECAkQAg#v=onepage&q&f=false, accessed June 13, 2023

No comments:

Post a Comment