This is the fifth in a series of eleven articles on

the top ten wilderness survival skills, things you should know before you go

into the wilderness. To read the

previous article go HERE

– Author’s Note

The Number

Five, Top Ten Wilderness Survival Skill: Shelter

knowing how and when to take shelter from the elements and why it is vitally important to do so.

The “Rule of Threes”, graphic by the Author.

After

caring for any injuries, finding a shelter is your next priority when there is

a wilderness emergency. You can only

survive for about three hours without fire, or a shelter from the environment. Shelter comes before a fire, because a windbreak

and a shelter make it much, much easier to build a fire. It is hard to light a fire when you are

shivering or the wind blows out your matches, and wet tinder doesn’t burn well!

The Why...

There

are five ways that your body loses heat to the environment, and the “Big Three”

are wind (convection), wet (evaporation) and conduction.

The ways your body loses heat, from the Search and Rescue Society of British Columbia, HERE.

When

it is cold and damp you will need shelter to prevent hypothermia, which is a

dangerous dropping of your body’s core temperature1. And the wind and the

evaporation it causes will have a chilling effect and hasten hypothermia.

Your

first line of defense for temperature regulation and shelter against the wind,

the wet, and the cold are your clothes.

Always dress in layers for the worst weather you might encounter. Maintaining your body temperature in the

normal range of 98.6oF (37oC) is your priority!

In

addition to your clothes, whenever you go into the woods, you should always

bring the means to make an emergency shelter to protect yourself from the cold

and the wet. It might be as simple as a

poncho or a couple of large of heavy-duty trash bags, or even maybe, a tent.

The simplest shelter is a poncho, here the Author is wearing his Swiss Military Alpenflage Rain Cape, photograph by the Author.

One

or two, depending on your size, of three or four mil, 42 to 60-gallon,

heavy-duty contractor trash bags will make a good short-term emergency shelter

from the wind, the rain, and the cold.

The Author in a trash bag shelter, photograph by the Author.

If

you can’t find orange trash bags, clear ones are better than black ones, as far

as being seen by searchers is concerned.

Black colored or clear trash bags will work, but brightly colored trash

bags, like the orange colored ones, are the best because they make it easier to

see a misplaced person.2

...Seeking

Shelter from the Ground

When you sit or lay down on

the ground, you will lose body heat to it by conduction. So, always build a bough bed3

under you to insulate you from the heat stealing snow or cold ground. Evergreen branches are the best, but you can

use anything to make a bough bed. Whenever

you see the word “bough”, remember that you can use other things if they

are fine at the tips and no thicker than your thumb at the stem, such as branches

with or without leaves, cattails, goldenrod stems, ferns, clover, or

grasses. Whatever you use should be dry,

so shake off any moisture or snow on it, before using it for your bough bed.

Building a bough bed, based on Bushcraft by Mors Kochanski, step one, building the base. Graphic by the Author.

In

a survival situation, use the Mors Kochanski method of building a bough bed and

put bare branches or saplings bigger than your thumb on the ground first, as a

base (the straight lines in the picture above).

Building a bough bed, based on Bushcraft by Mors Kochanski, step two, building an insulating mattress of boughs. Graphic by the Author.

If

you are using evergreen boughs, cut off the branches from the base of the tree

to the crown, and lay the bottom branches down first, then lay the middle

branches down next and finally place the top branches down last. Put the branches, or whatever you are using

to build your bough bed, in a chevron pattern with the boughs making an angle

close to 90o on top of the base.

No

matter what you use to build your bough bed it is going to compress under your

weight, and according to Mors Kochanski, you need to have a compressed

thickness of at least 4 fingers, or about 3-1/2 inches (about 9 cm) of dead air

space between you and the ground or snow as insulation. Some experts recommend 2 to 3 feet, or 61 to

91 cm, of uncompressed branches to achieve the necessary compressed

thickness. However, when I conducted an

experiment and built a 28 inch, or 71 cm, high pile of balsam fir boughs, it compressed

to 18 inches, about46 cm, high under my weight.

So, to get 4 fingers, or 3-1/2 inches (or 9 cm) of compressed mattress,

you will have to start with a bough bed that is just over 6 inches, or about 15

cm, thick.

...Seeking

Shelter Against the Wind

Photograph by the Author.

There

are a lot of several types of winds that you must take shelter from, storm

winds, prevailing winds and offshore, onshore and valley winds. Understanding how and from what direction

they blow is important, especially if you are trying to shelter from them.

Offshore,

onshore and valley winds are some of the most common winds and the easiest to predict

since they are generated by the daily warming and cooling cycle. What you must remember about these winds is

that at night the land cools faster than the water, the rising warm air over

the water pulls the cooler air over the land away from the shore as an offshore

or land breeze. And the air above mountain

slopes and hills cools faster at night than the valley air and the warmer

valley air rises and pulls the cooler hilltop air downslope and down-valley. During the day, this cycle reverses.4

Since

you lose heat to the wind by convection, always try to find a windbreak and

stay out of the wind. This reduces the

effects of wind chill and at the same time protects you from wind-blown rain,

sleet, and snow. The lee side of the

windbreak, the side downwind, or behind the windbreak, will offer you

protection from the wind. Oh, and

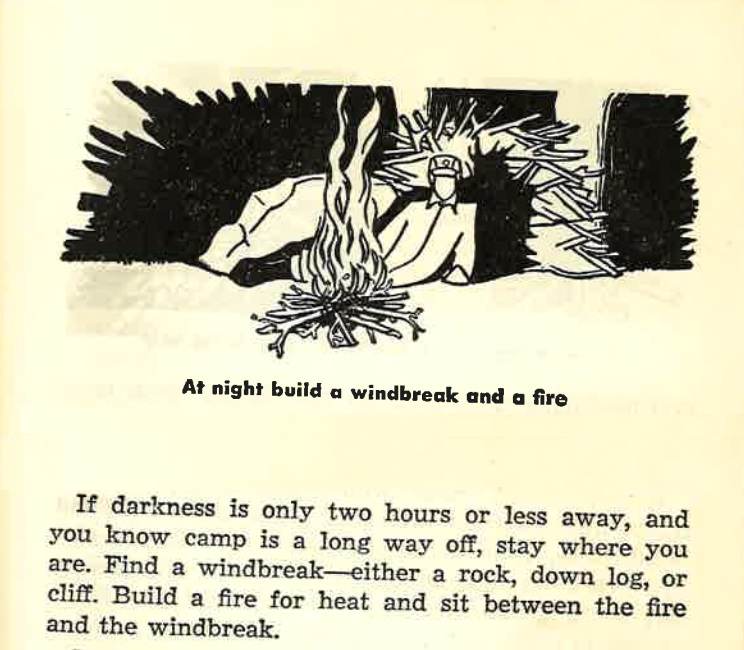

remember you must sit between the fire and the windbreak5.

An excerpt from Handbook For Boys, by the Boy Scouts of America, June 1953, page 157.

You

can either find windbreaks, like large rocks, fallen trees, or thickets and

groves of trees, or you can build them yourself from the materials at hand in

the wilderness. There are two types of

windbreaks, solid ones like rocks, walls and logs, and permeable ones like

groves of trees and thickets, which are also called shelterbelts.

An illustration from “But If You Do Get Lost”, Outdoors USA: 1967, by Kenneth M. Cole, page 91.

The

area of wind protection downwind from a solid windbreak is about fifteen times

the height of the windbreak. So, if you

build a wall or find a fallen log or big boulder that is three feet or almost 1

meter high, it will block or reduce the wind for about fifteen times the height

of the windbreak, which at 3 feet, or almost 1 meter, will be 45 feet or just

over 14 meters.

In

the winter, a solid windbreak that is three feet or almost 1 meter high, will

create a snow-drift zone downwind of the windbreak, equal to the height of the

windbreak times five, which in this example is 15 feet or almost 5 meters, long. However, the area behind, or in the lee of, the

windbreak out to about 6 feet or 2 meters, which is a distance equal to two times

the height of the windbreak, should be mostly drift free.

A

grove or stand of trees also acts as a shelterbelt or permeable windbreak and when

the wind blows through a grove of trees, with a vegetation density of 50 to

60%, the wind is both forced over and through the trees. The trees will block and slow the wind for at

least fifteen times the height of the grove6, which if it is 30

feet, or almost 10 meters tall, will extend downwind

from the edge of the grove for 450 feet, or almost 135 meters. This wind reduction can be as much as 70%

within the first 100 feet, or roughly 30 meters, dropping to 50% out to 200

feet, or 60 meters, from the downwind edge of a grove of trees.

During

the winter, if you are downwind of an approximately 30 foot or almost 10 meters

tall grove of spruce trees, the wind and snow will create a drift zone downwind

of the trees that can extend as far as 150 feet to 300 feet, or about 45 to 90

meters. This distance is the height of

the grove of trees, times a factor of five to ten.

So,

during the spring, summer or fall, the best type of windbreak is a thicket or

grove of trees, and the best spot for protection from the wind, would be

somewhere within five to ten times the trees height, downwind from the edge of

the grove. However, during the winter,

the best spot to avoid snow drifts would be downwind about ten times the trees

height away from the downwind edge of the grove. This spot will give you the best protection

from the wind and it will also put you beyond the snow drift zone. You can also build your own windbreak,

downwind from a grove of trees and combine the best of both windbreaks

So,

in a wilderness emergency take shelter from the wind, the wet and stay off the

cold, cold ground!

Don’t forget to come back next week and read “Pumpkins...Boil

‘em, Mash ‘em, Eat ‘em in a Stew!©”, where we will talk about the history of

pumpkins and what you do with your left over Halloween decorations.

Photograph by the Author

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and look for me

on YouTube at Bandanaman Productions for other related videos, HERE. Don’t forget to follow me on both The

Woodsman’s Journal Online, HERE,

and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube. If you have questions, as always, feel free

to leave a comment on either site. I

announce new articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds, on Instagram at

bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch for me.

That

is all for now, and as always, until next time, Happy Trails!

Notes

1

Don’t forget that when it is hot, you will also need a shelter from the Sun,

because hyperthermia, an elevated body temperature, the opposite of hypothermia,

can be just as deadly. And the wind, and

the evaporation it causes, are also an enemy, because when it is hot it will dehydrate

you. So, if you are going to be in a hot

and dry area always bring a tarp or some way of building a Sun shield, and

don’t forget that at night deserts can get very cold. For more on desert survival read “Desert

Survival: Information For Anyone Traveling In The Desert Southwest, 1962 ©”, HERE.

2 For

more on how to use a poncho or trash bag as a shelter read, “Using your poncho

or a trash bag as an Emergency Shelter ©”, HERE.

3

Bough beds are also called ground beds, bush beds or browse beds and have been

used by travelers in the wilderness for centuries to insulate themselves from

the heat robbing ground. For more read “Making

an Emergency Bough Bed©”, HERE.

An excerpt from Weather,

by the Boy Scouts of America, page 9

|

|

For

more on the wind and the other four W’s that you have to watch out for when in the

wilderness, read “Woodcraft 101: Putting Up A Tent ©”, HERE.

An excerpt from “But If You Do Get Lost”, Outdoors USA: 1967, by Kenneth M. Cole, page 91.

6 The

actual area of wind protection, downwind from a grove of trees, is between

fifteen to twenty times the height of the trees.

Sources

Boy Scouts of America, Handbook For Boys,

[Boy Scouts of America, New York, New York, June 1953], page 157

Boy

Scouts of America; Weather, [Boy Scouts Of America, Irving, TX; 1992],

page 9

Search

and Rescue Society of British Columbia, https://www.sarbc.org/hypothermia,

accessed November 2, 2021

United States Department of Agriculture, Outdoors

USA: 1967 Yearbook of Agriculture, [United States Government Printing

Office, Washington, DC, 1967], p 87-89, https://archive.org/details/yoa1967/page/n3,

accessed November 2, 2019

No comments:

Post a Comment