Fires

and aircraft crashes go together.

Statistics vary, as to how often aircraft burn upon crashing, from 87%

catching fire upon impact with the ground, to 5% to 18% of all crashes burning

upon crashing1.

Also,

surveys show “that most people think they actually have about 30 minutes to

get out of a burning plane”, however, according to theFAA, the reality is

that between 90 and 150 seconds after the cabin catches fire and fills with

flames and smoke, a violent explosion of superheated gases will occur, called a

“flashover”, and after that escape is impossible.2

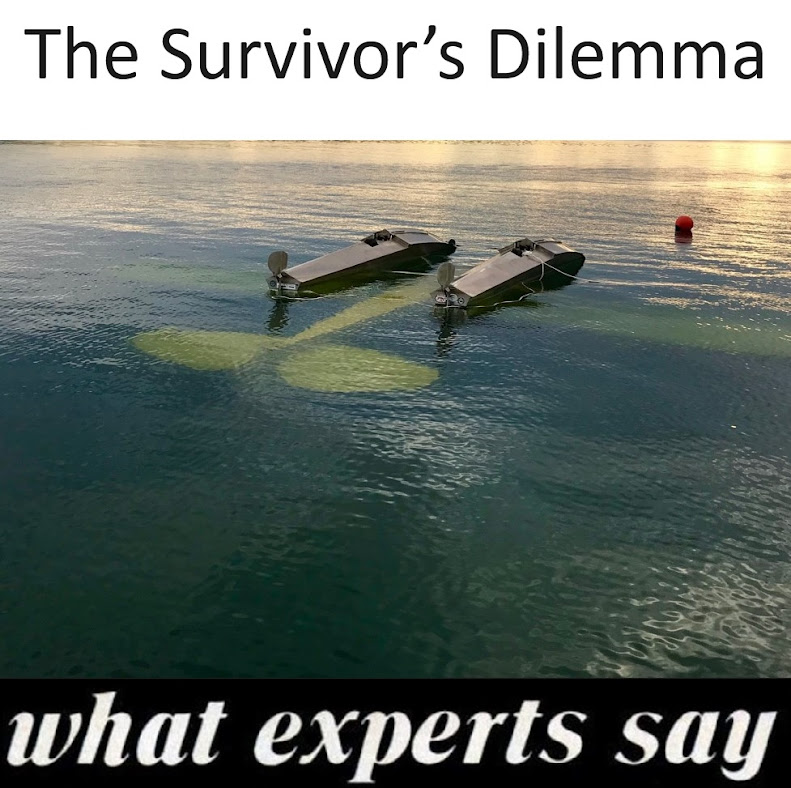

But

what if your plane crash lands on a lake or river, do you have more time to

escape, since it isn’t likely to catch fire in that case?

No,

because NOW you must worry about drowning!

The Transportation Safety Board (TSB) of Canada completed a study in 1994,

that found that of the 48% “(103) of the 216 fatal accidents known to terminate

in the water”. Further they found

that of the 168 fatalities in the 103 crashes which terminated in the water,

52% died from drowning.3 They

also wrote that often the aircraft end up floating upside down, suspended by its

floats. And to top it all off, The

Second World Congress on Wilderness Medicine, 1995, noted in the presentation

on “Escape Considerations for Fixed Wing Aircraft”,

that there is a tendency for fixed wing aircraft to sink nose first, because of

the weight of the engine. This forces

survivors into the tail section, where there is no way to exit the plane as it

sinks, so they drown.

This

is why in Part One, HERE,

I asked, if you had only 60 seconds to choose just four things to help you

survive in the arctic wilderness after a plane crash, what would you

choose? And more importantly, why would

you choose them?

So,

which four items did you think would help you the most to survive the snow and

cold, until rescuers realize you are overdue and come looking for you in 15

days or so? Hopefully, you used the rule

of threes to help you decide which of the 15 items were most important to your

survival.

In 1974, the experts that

ELM questioned for the correct answers for the “Subarctic Survival Situation”

were the Canadian Para Rescue Specialists of the 413 Transport and Rescue

Squadron. This squadron, which was

stationed at Summerside, Prince Edward Island, was responsible for air and sea operations

in Quebec, Newfoundland, Labrador, and the arctic regions. These specialists had received rescue and

survival training in both the subarctic and arctic, and what follows are their rankings

and their reasons (in italics).

1-- 13 Wood Matches (in a metal screw top,

waterproof container)

The experts consider this

to be the single most critical item.

Protection from the cold and a source of fire are absolutenecessities. While other means to start

a fire exist, they are unreliable in the hands of amateurs. At night, the fire could also serve as a signal. Since the terrain in this area is high,

aircraft in and out of Schefferville might spot it.

2-- Hand Ax

A continuous supply of

wood is necessary to maintain the fire.

Therefore, a hand ax may be the most frequently used item in camp. It is also useful for clearing a sheltered

campsite, cutting boughs for ground insulation, constructing a frame for the

shelter, and butchering in the event that the group locates and kills caribou,

bear, or moose.

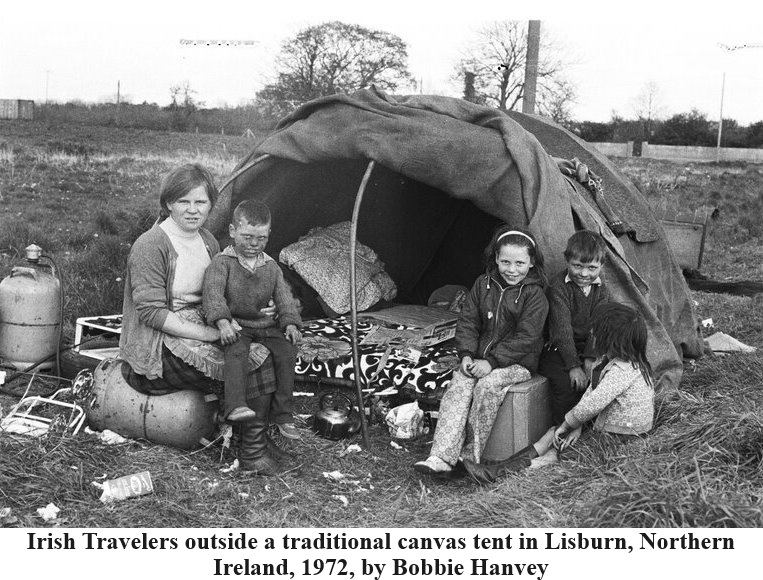

3-- 20'x 20' (7m x 7m) Piece of Heavy Duty

Canvas

Prevailing winds of 13-15

knots (15-17 MPH or 24-28 KPH) will make some protection

necessary. The canvas can adequately

serveas protection from the elements-rain, snow, and sleet. Spread on a frame and secured by rope, it

makes a good tent or could be used as ground cover. Rigged as a wind screen, it acts as

insulation and holds heat. Its width,

contrasting with the terrain, makes it easily spotted in an air search.

4-- 1 Sleeping Bag (arctic type,

down-filled with liner)

A possible 14 nights in

the subarctic would render this type of sleeping bag (good to -20° F or -29° C)

a key factor in survival. To maximize its

effectiveness, survivors must try to keep the bags dry at all times.

5-- Gallon (4 &) Can of Maple Syrup

This item has two

possible survival uses. The maple syrup

is a source of quick energy and some nourishment. The can itself, ifused for cooking and water

collecting, is helpful. Since food will

eventually be a problem, survivors must value any source. Since most plants in the subarctic region are

edible, especially after boiling, the can is important. Various green plants such as arctic willow

and dandelion, as well as evergreen inner bark, may be boiled and eaten. Snow should not be eaten. It will cause dehydration rather than relieve

thirst. If possible, survivors should

melt ice instead of snow. It takes 50

percent more fuel to obtain a given amount of water from snow than from ice.

6-- 250 ft. (75 m) of 1/4-lnch (0.5 cm)

Braided Nylon Rope, 50 lb. (25 kg) test

The nylon rope can tie

poles of wood together as supports for the shelter, or it can be used to string

the canvas between two trees. Threads of

the rope could be used for a fishing line.

Additionally, survivors could use the rope to hang fresh meat away from

predators (bears or arctic wolves). It

could also be used to construct a willow net for fishing, to construct various

traps (including snares and deadfalls), or to string a hunting bow.

7-- A Pair of Snowshoes

The ability to travel in

the subarctic is related to over-the-snow traveling equipment, since unfrozen rivers

and lakes constitute aserious barrier. Snowshoes would be useful for traveling around

camp while constructing a shelter and hunting.

Makeshift snowshoes could be constructed later out of rawhide or rope

with branches, for travel after the freeze (about December 1 ). Rivers are the highways of the north in summer

and winter, but not in spring or fall. Snow

must have a crust over it to expedite travel.

Soft snow is exhausting to walk through.

8-- 1 Aircraft Inner Tube (for a 14-inch

[35 cm] tire-punctured)

You could construct a

slingshot from the inner tube. Birds are

plentiful during the long winter; even owls, ravens, and ptarmigans are

visible. Rock ptarmigans are easily

approached and killed with rocks or a slingshot. Black smoke could easily be produced from

burning strips of rubber, for immediate and more effective signaling. Using the rubber, survivors could make

bindings and spring mechanisms for animal traps.

9-- Safety Razor Shaving Kit with Mirror

The mirror is the most

powerful tool you have for communicating your presence if the sun is out. In the sunlight, a simple mirror cangenerate

five to seven million candlepower of light.

However, heavy clouds cover the sky three quarters of the time, with

only one day in ten being fairly clear. The razor blades (along with the pocketknife)

could be used as cutting edges.

10 -- 1 Operating 4-Battery Flashlight

Because of the length of

time survivors may have to wait before help arrives, the flashlight will be needed

as an emergency source of light in addition to the campfire. Otherwise, it can be held in reserve as a

nighttime signaling device. However, the

battery efficiency will drop with the temperature.

11-- Fifth (750 ml) of Bacardi Rum (151

proof)

The rum could be used for

medicinal purposes, as an anesthetic or disinfectant. The bottle might be useful as a water

container.Although liquor is commonly

thought of as providing body warmth, it actually causes a loss of body

heat. Drinking large quantities of

alcohol will speed up hypothermia, a gradual lowering of the body's

temperature, which can be fatal.

Author’s Note – As a disinfectant,

alcohol below 50% ABV are not good at killing bacteria, fungi, and

viruses. However, alcohol between 60% to

90% ABV is the best to use as a disinfectant. Since 151 proof Bacardi rum is 75.5% alcohol by

volume (ABV), it would make an excellent disinfectant and could also be used

with a cotton wick as a spirit lamp, something the Canadian Para Rescue

Specialists hadn’t thought of. Any alcohol

above 50% ABV, or 100 proof, will burn well and not extinguish easily. As a side note, alcohol between 40% to 50%

ABV will also burn, but only fitfully and is liable to go out easily.

12--Wind-Up Alarm Clock

If used as a time piece,

the clock makes it possible for survivors to locate North. (At 2:50 p.m., line up the small hand with

the sun and a stick. North is centered

between the 7 and 8 o'clock positions in the North Temperate Zone.) The intact

glass surface can be used as a reflective signal. Use the clock itself to establish a routine in

camp, and to determine signaling and fire watch times. If dismantled, internal workings can be used

for fishing hooks and lures.

13-- Magnetic Compass

A compass in this area is

unreliable. Proximity to the magnetic

pole produces serious inaccuracies. The iron

ore deposits will producewide variations in readings. One expert, who is very familiar with the

territory, indicated that it is impossible to walk 100 yards (91 m) and return

accurately using a compass in this area.

14-- Book Entitled, North Star Navigation

The book might be helpful

for starting a fire or as entertainment. But since the book's directions could only be

used at night, it would be dangerous as a navigation aid. North star navigation in the subarctic is not

reliable because the North Star is so high in the sky. Therefore, direction is difficult to determine.

Author’s Note -- If you

go as far north as the North Pole, the North Star, also known as Polaris, will

appear directly overhead, which makes it very hard to determine the correct

path north. As you travel south,

the North Star drops closer to the northern horizon and identification of the

direction north becomes easier.

15--

Bottle of Water Purification Tablets

The water in the area is

as fresh and pure as any in the world.

The bottle, however, could be used for something. Pond water is slightlysafer to drink than

river water.

What’s

your score?

· First.

Calculate your Individual Score by subtracting

your Individual Rank for each of the 15 items from the Experts' Rank for each

of the 15 items. Disregard negative

signs and record the differences in the column labeled "Step 3-Difference

Between Steps 1 & 2”.

· Second. After recording your scores for all 15 items

in column "Step 3”, first total the scores of the first four items and

write it above the “/” at the bottom of column "Step 3”. Next total the scores for ALL 15 items and

record it below the “/”at the bottom of column "Step 3”.

· Third. To find out if you survive or not, compare

your “Individual Score” for the first four items and then your “Individual

Score” for all the items against the charts below.

Did you survive the first night?

To find out if you

survive the first night compare your “Individual Score” for the first four

items against the chart below:

· 0 –

14 points: You survive the night without

freezing to death!

·

15 -

16 points: When morning arrives, you are

alive, but shivering and you can’t feel your fingers. Surviving until noon will be a challenge!

·

17 -

18 points: When morning arrives, you are

hypothermic and barely alive, you die before noon!

·

19 +

points: When the rescuers arrive, they find your

stiff and frozen corpse buried in the drifted snow!

Did you survive the first night?

To find out if you

survive until the rescuers arrive, compare your “Individual Score” for ALL 15

items to the chart below:

· 0 –

50 points: When

the rescuers arrive, they find you alive and hungry, but with no injuries!

·

51 - 60

points: When the

rescuers arrive, you are alive, but shivering and you might lose some of

your fingers and toes to frostbite!

·

61 - 70

points: When the rescuers arrive, you

are hypothermic and barely alive, you might die before the rescuers can get you

to the hospital!

· 71 + points: When the rescuers arrive, they find your

stiff and frozen corpse buried in the drifted snow!

Don’t forget to come back next week and read “A Bender©”, where we

will talk about making a shelter out of next to nothing!

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and look for me

on YouTube at BandanaMan Productions for other related videos, HERE. Don’t forget to follow me on both The

Woodsman’s Journal Online, HERE,

and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube. If you have questions, as always, feel free

to leave a comment on either site. I

announce new articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds, on Instagram at

bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch for me.

That

is all for now, and as always, until next time, Happy Trails!

Notes

1 Major

Ray Gordon; “Cabin Fires” Flying Safety, January 1986, and David M. Eiband and A. Martin Eiband; “On Crashing and

Burning”, Flying Safety, July 1981

2 “Is

it rare to survive a plane crash?”, September 3, 2023

3 TSB

of Canada; “A Safety Study of Survivability in Seaplane Accidents”

Sources

Delly,

John Gustav; “How to Make/Modify and Use an Alcohol Lamp”, [©2023 The McCrone

Group], https://www.mccrone.com/mm/how-to-makemodify-and-use-an-alcohol-lamp/,

accessed October 21, 2023

Eiband,

David M. and Eiband, A. Martin; “On Crashing and Burning”, Flying Safety,

July, 1981, page 8 to 9, https://books.google.com/books?id=fP6Dz9R5H9cC&pg=RA6-PA8&dq=%E2%80%9COn+Crashing+and+Burning%E2%80%9D,+Flying+Safety,&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjj2__r0IeCAxXarokEHZ9HCiAQ6AF6BAgHEAI#v=onepage&q=%E2%80%9COn%20Crashing%20and%20Burning%E2%80%9D%2C%20Flying%20Safety%2C&f=false,

accessed October 21, 2023

Gordon,

Major Ray; “Cabin Fires” Flying Safety, January 1986, page 6 to 7, https://books.google.com/books?id=MJuxMs0WZgIC&pg=PA6&dq=%E2%80%9CCabin+Fires%E2%80%9D+Flying+Safety&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi78ee20IeCAxUlmYkEHXjCAc4Q6AF6BAgNEAI#v=onepage&q=%E2%80%9CCabin%20Fires%E2%80%9D%20Flying%20Safety&f=false,

accessed October 21, 2023

Lafferty,

J. C., and Eady, P. M.; “Subarctic Survival Problem”, Experiential Learning

Methods, [Grosse Pointe, MI 1973]

Love The Maldives; “Is it

rare to survive a plane crash?”, Love The Maldives, September 3, 2023, [©

2020 - LoveTheMaldives.com by Flamingo Media SL], https://lovethemaldives.com/faq/is-it-rare-to-survive-a-plane-crash#:~:text=Surveys%20show%20that%20most%20people,everything%20and%20everyone%20in%20it,

accessed October 21, 2023

LTR

Training Systems, “Escape Considerations for Fixed Wing Aircraft”, The

Second World Congress on Wilderness Medicine, [August 8-12, 1995, Aspen,

Colorado], page 239, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA300465.pdf,

accessed October 21, 2023

TSB

of Canada; “A Safety Study of Survivability in Seaplane Accidents”, Report No.

SA9401, [Minister of Supply and Services Canada, 1994], https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2010/bst-tsb/TU3-2-9401-eng.pdf,

accessed October 21, 2023

United States Department of the Army, Soldier's Handbook for Individual Operations

& Survival in Cold Weather Areas, DA PAM 350-44, [Headquarters,

Department of the Army, 1972]

page 64,

https://books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5QadLeFBQz1f65540a5Aja-c1Ru6FneeOZXKBmGpVSbh0numuZLFwkHax_Ht8ZdJFTOfprhvA8kU7lvtg43R3UbtX1Fm3mjx6O3BQ_eGQ8vDcfnOFRgFVgSrfissBGddiE7gieE0BCdttU0OZsz9W9pJ_riV-TewwuAP222lJJu4LnzX_BFLkmR8YIC5rewBxZde2XqKCJjLq0HVJ7Iqj5RMWg9r3Lp49OW0DcNa-HLNKcp8bGZhf-YFF9edBU79ZaWQ2h_FnNbV34lvP0n5BQUs5BvQ8aOVNAJiVVRTOtgBfoyq_jWs,

accessed October 21, 2023

_-_Single_color%20ed%2010%20percent.jpg)