Woodcraft and Camping Skills from the 18th to the 21st Centuries, Survival Skills, Lost Prevention, Gear Reviews and Much More...

Sunday, September 29, 2019

But If You Do Get Lost – Emergency Shelters ©

You are “misplaced” in the woods and

this is your bed tonight, picture by the author.

So,

it happened! It had to happen to you

eventually, you know; it happens to everyone eventually. Maybe you got turned around and now you are

“misplaced”, and you have no idea on how to get back to where you were. Maybe, you slipped and fell, and now you are

too injured to get out of the woods by yourself. Or, maybe the Sun is going down behind the

trees and you have less than two of daylight left. What do you do now?

You

need to find shelter, of course! But

what should you look for?

Graphic by the author.

Summer

or winter, it doesn’t matter, the elements are your worst enemy; humans can’t

survive heat or cold, wet or wind for long without a shelter. Because protecting yourself from the elements

means different things in different climates and at different times of the

year, the type of shelter that you build will depend on where and when you are

building it. It is true, that a lot

could, and has, been written about how to build a shelter, however today, I am

writing about things that you should think about before, and as, you build your

shelter.

Location,

location, location…and the 5 W’s

Whenever

you set up a campsite in the wilderness, you should always consider the 5 W’s,

wind, water, widow-makers, wood and wildlife, before you choose a location.

Wind

You

must treat wind with respect and plan for it when you choose the location of

your shelter, because in a survival situation wind can be your enemy and kill

you fast if you let it. Wind and wind-chill

it can lower the “real-feel temperature” and bring on hypothermia; it can suck

the moisture out of you and bring on dehydration, or it can blow down branches

and trees on you and squash you flat. On

the other hand, wind can blow mosquitos and other bugs away from you and your

campsite. So, what type of winds are

there?

Prevailing winds worldwide, from Moon

Joon Kim

Prevailing

winds are, according to the Oxford dictionary, “a wind from the direction

that is predominant at a particular place or season”. It is always important when you travel or

camp in the wilderness to know the usual wind direction, when canoeing it can

help you stay in the calm water on the sheltered lee side of the shore or if

you put your camp on the windward shore, it can help blow the bugs away from

your camp. It is important to remember

that prevailing winds are not constant all day long, as Alan Innes-Taylor noted

on page 53, when he wrote of prevailing winds in the Arctic Survival Guide:

“Fair weather winds usually decrease at night”. In Algonquin Provincial Park and much of

northeast Canada and the United States, fair weather winds usually blow from

the northwest to the southeast during the day.

Windward and leeward sides of hills

or mountains, modified from Eliane Truccolo

Offshore, onshore and valley winds,

modified from Eliane Truccolo

Onshore winds, from Fig. 2-10, Aviation

Weather Student Guide

|

Offshore winds, from Fig. 2-11, Aviation

Weather Student Guide

Offshore, onshore and valley winds are all very similar and are both generated by the daily warming and cooling of the

land. The differences in the specific

heat of land and water causes the land to warm and cool more quickly than water,

during the day this causes warming and rising air over the land and descending

or cooling air over the water resulting in an onshore or sea breeze. At night the process reverses with the land

cooling quicker faster than the water, which cause descending cool air over the

land and rising warm air over the water and creates an offshore of land

breeze. Onshore breezes seldom penetrate

far inland, but they are usually stronger than offshore breezes.

Mountain and valley winds, from Fig.

2-12, Aviation Weather Student Guide

In

the daytime mountain slopes and hillsides are heated more quickly by the Sun

than valley bottoms, and these slopes warm the surrounding air through

conduction. This warmed air rises and then

later cools and sinks back down towards the valley floor, forcing the air from

the valley floor up the mountain or hillside, completing the cycle of

circulation and creating an upslope and up valley wind. At night the air in contact with the mountain

slope or hillside cools faster than the valley bottom because of outgoing

terrestrial radiation and this denser cool air flows down slope and down valley

and forces warmer valley bottom air upwards, creating a circulation pattern and

downslope and down valley winds.

| Excerpts from the Arctic Survival Guide, p. 53, by Alan Innes-Taylor |

All

of this is important, because you want to face your shelter so that the front

is perpendicular to the general flow of the wind.

Water

and Widow-makers

The second and third of the 5 W’s are water and

widow-makers. While you want to be near

drinking water, setting up your shelter near that babbling brook is often a bad

idea, as a storm far upstream can quickly turn that tame stream into a raging

torrent and wash you away. Also, you

should look for a level area half-way between the summit of the hill and the valley

bottom, as the cold night air collects in low spots and valleys and the summits

of hills are always cold. It is

often significantly warmer half-way up a hillside, between the crest of the

hill and the valley bottom and far safer from flooding. Always look up and around your planned campsite

and make sure there a no dead trees, snags or widow-makers stuck in the

branches above you, just waiting for the right wind to come crashing down on

you. And lastly, don’t shelter under the

tallest tree in the forest, it is a lightening rod! If possible, shelter in a grove of equal

sized trees. Also avoid hill-tops and

exposed cliff faces can also attract lightening, so don’t shelter at the base

of the tallest cliff in the area or on the top of the hill.

Wood

An excerpt from “How Not To Get

Lost”, by Charles Elliott

The

fourth of the 5 W’s is wood, the area that you choose for your campsite should

have plenty of firewood and building materials, such as leaves, boughs, bark,

branches, etc.

Wildlife

The

last of the 5 W’s is wildlife, be careful of setting up your shelter on game

trails, near swampy areas that breed mosquitos or in a rock shelter that is

already called home by one of the locals.

And

now that you have some ideas on where to build your shelter, the first and most

basic shelter you need, is the one that will insulate you from the cold, cold

ground. If you have ever slept directly on

the ground, when the night-time temperatures drop close to freezing, as I have

once upon a time, you will know how painful it is as the ground sucks the heat

out of your kidneys! I can tell you from

personal experience that, insulation between you and the ground is your

friend. You should always build a

shelter bed before you build any other shelter. Mors Kochanski, a well-known survival expert,

wrote that shelter beds or emergency bough beds should have a compressed

thickness of at least 4 fingers or about 3-1/2 inches of dead air space between

you and the ground or snow as insulation.

Earlier in 2019, I experimented with making a bough bed and discovered

that a 28 inch (72 cm) high pile of boughs compressed down to 18 inches (46 cm)

of insulation when I sat down on it.

Shelter beds insulate your sleeping body from the cold ground and make

you more comfortable and allow you to sleep better. For more on shelter beds, read “Making an

Emergency Bough Bed”, HERE and watch “Building An Emergency Bough Bed”, HERE.

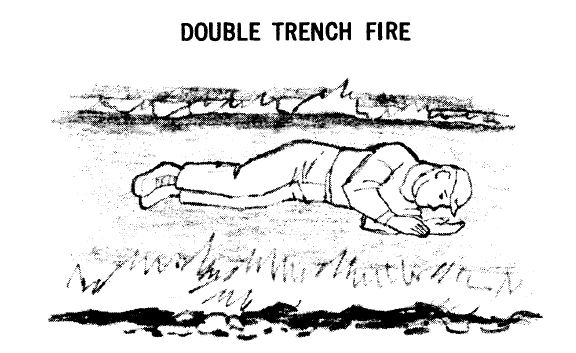

There

are two types of shelters, found shelters and built shelters, and of most are

reflector shelters. Found shelters are

exactly as they sound, shelters that you find in the wilderness and they can be

a rock shelter, cliffside or big boulder, a blown down log or an uprooted tree;

or simply a large tree that you can lean against during the night. Built shelters are lean-to’s, debris beds or

double trench fires, these last two are the only two that are not reflector

shelters. Reflector shelters are any

open or roofed shelter where you are between the reflector and your fire. Lean-to’s or debris shelters take more time

and energy to build but, are the most weatherproof of shelters. Below are some examples of shelters that you

could find or build in an emergency.

|

| An illustration of a found, reflector type of shelter from “But If You Do Get Lost”, Kenneth Cole, p. 90 |

A blown down tree and upturned root ball, a found, reflector type of shelter, photo by the author

Looking out from underneath a rock

shelter, an example of a found reflector type of shelter, photo by the author

|

| An illustration of a built reflector type of shelter from Arctic Survival Guide, by Alan Innes-Taylor, p. 54 |

|

| An illustration of a built reflector type of shelter from Arctic

Survival Guide, by Alan Innes-Taylor, p. 54 |

|

An illustration of a built reflector

type of shelter from Arctic Survival Guide, by Alan Innes-Taylor, p. 55

An illustration of a built shelter

which may or may not be a reflector type of shelter from “But If You Do Get Lost”,

by Kenneth Cole, p. 90

An illustration of a built

non-reflector type of debris shelter, from Outdoor Survival Training For

Alaska’s Youth, by Dolly Garza

An illustration of a built

non-reflector type of shelter from “But If You Do Get Lost”, by Kenneth Cole,

p. 90

This

is a thumbnail sketch of building or finding a shelter in a survival emergency.

Hopefully you will never have to build

or find one in a real emergency, however they are a lot of fun to find or build

for practice.

An upturned root ball reflector

shelter, nighty-night, photo by the author.

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and my videos at

BandanaMan Productions and don’t forget to follow me on both The Woodsman’s

Journal Online and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube, and if you

have questions, as always, feel free to leave a comment on either site. I announce new articles on Facebook at Eric

Reynolds, on Instagram at bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds,

so watch for me.

Sources

Cole,

Kenneth M., Jr.; “But If You Do Get Lost”, Outdoor USA: 1967 Yearbook of Agriculture [United

States Department of Agriculture, United States Government Printing Office,

Washington, DC, 1967] p. 89-91, https://archive.org/stream/yoa1967/yoa1967_djvu.txt,

accessed 6/16/14

Elliott,

Charles; “How Not To Get Lost”, Outdoor USA: 1967 Yearbook of Agriculture

[United States Department of Agriculture, United States Government Printing

Office, Washington, DC, 1967] p. 87-89, https://archive.org/stream/yoa1967/yoa1967_djvu.txt,

accessed 6/16/14

Garza,

Dolly; Outdoor Survival Training For Alaska’s Youth: Student Manual,

[Alaska Sea Grant College Program, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 1998], p. 13,

https://www.nwarctic.org/cms/lib/AK01001584/Centricity/Domain/507/OutdoorSurvivalTraining-StudentManual.pdf

, accessed 12/4/2017

Kim,

Moon Joon; “Essays on Long-Range Transport of Air Pollution and Its Health

Outcomes”, [Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North

Carolina, 2017], p. 4, https://repository.lib.ncsu.edu/bitstream/handle/1840.20/34686/etd.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y,

accessed 9/28/19

Kochanski

Mors L.; Bush Craft, [Partners Publishing, Edmonton, AB., 2014] p.174

Aviation Weather Student Guide, “Atmospheric

Mechanics of Winds, Clouds and Moisture, and Atmospheric Stability”, http://navyflightmanuals.tpub.com/P-303/Sea-And-Land-Breezes-43.htm,

[Integrated Publishing, Inc.], p. 2-11 to 2-13, accessed 9/28/19

Truccolo,

Eliane; “Assessment of the wind behavior in the northern coast of Santa

Catarina”, Revista Brasileira de Meteorologia, Vol 26, 3, September 2011,

p. 451-460, http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102-77862011000300011,

accessed 9/28/19

Vliet,

Russ; A Manual of Woodslore Survival, [Philmont Scout Ranch, Cimarron,

New Mexico, 1950], p. 7-8

Sunday, September 22, 2019

The Trinity of Trouble ©

|

Arctic

Survival Guide, 1964, edited and compiled by Alan

Innes-Taylor

|

Recently

I have been reading the Arctic Survival Guide, a rather hard to find

survival guide; by Alan Innes-Taylor1, an early expert in northern

survival.

“…survival

is terribly unforgiving of excessive optimism,

carelessness, and neglect. Remember

these three – they are the trinity of trouble…”, Alan Innes-Taylor, Arctic Survival

Guide, p. 46

This

guide was written in 1964, for the aircrews of the Scandinavian Airlines

Systems (SAS), and on page 46 the author wrote about the “trinity of trouble”; which he explained was excessive optimism,

carelessness and neglect.

The

trinity of trouble seemed to me

to be an easy to remember survival rule and so today I am going to write about

the things you should not do, if you want to survive an emergency in the

wilderness.

Unfortunately,

Mr. Innes-Taylor, on page 46 in the Arctic Survival Guide, never fully

explained what he meant by the statement “…excessive

optimism, carelessness, and neglect…”.

However,

in the Arctic Survival Guide, he did include two statements that provide

some insight into his thinking.

“To date, reviews of polar crashes continue

to reveal avoidable hardships due to overestimation of personal

capabilities. In too many instances

deaths may be attributed to lack of appreciation for the physical demands of

the conditions as actually found”, Alan Innes-Taylor, Arctic Survival Guide, p. 46

“Finally, the infrequency of crash landings

can lull the participants on long flights over the polar regions into a false

sense of security resulting in non-survival when all have landed safely”, Alan Innes-Taylor, Arctic Survival

Guide, p. 48

Another

source which offered some insight into Mr. Innes-Taylor’s thoughts on the

trinity of trouble, is the book Northern Survival, which was originally

compiled in 1967. Mr. G. D. Cromb, who

wrote the foreword, credited a number of unnamed contributors; however he only

mentioned one contributor by name, “Mr.

Innes Taylor of Whitehorse who had first-hand knowledge and experience in

northern Canadian living”.

I

believe that the following quotes from Northern Survival, if not

directly from the mind of Alan Innes-Taylor, are certainly derived from his

thoughts.

“The mental attitude that ‘it can’t happen to

me’ is dangerous in that the individual will not accept the situation as it

exists and is blind to reality”, Northern Survival, page 5

“Most people are inclined to over-estimate

their physical abilities. Be very

careful when trying to estimate your physical stamina…”, Northern Survival, page 5

I

believe that what Mr. Innes-Taylor was trying to communicate with the phrase, the

trinity of trouble, is that “excessive

optimism”2 and the “it

can’t happen to me”3 mental attitude, leads a person to have a “false sense of security”4; which

leads a person to have an “overestimation

of personal capabilities”5,

their “physical abilities”6 and “physical stamina”7; and finally to have a “lack of appreciation for the physical demands of the conditions as

actually found”8;

all of which contributes to “non-survival”9. Additionally, I further believe that he

intended it to be understood, that excessive optimism, leaps directly to carelessness

and to neglect.

“But to expect is not enough; you must

anticipate and prepare for the unexpected” Survival: Training

Edition, AF Manual 64-3, page 1-4

So,

if excessive optimism leads directly to carelessness, then what are some

examples of carelessness? Carelessness

following an emergency in the wilderness usually involves not anticipating and

preparing for the unexpected. Some careless

errors that you might slip into include; wasting resources, supplies or

opportunities by not preparing in advance, perhaps by not building a shelter

before the storm arrives, or signals, before you hear the rescue plane; by

delaying setting up camp or not turning back on the trail until it is too close

to dusk; or by not sleeping and resting when you have the chance or it is in

your best interest to be out of the elements.

“…it pays to prepare for any

eventuality by carrying on your person a personal survival kit”, Survival:

Training Edition, AF Manual 64-3, page 1-4

Examples

of neglect, which follow carelessness, generally involve neglecting to prepare

for any eventuality in some way or the other.

Perhaps you have failed to leave a detailed travel plan with

someone. You should always leave detailed

travel plans with someone at your base of operations, these plans should

include who is traveling, where you are traveling, when you are leaving and

when you plan on being back. Another

example of neglect would be failing to prepare for emergencies by neglecting to

carry a personal survival kit, first aid kit or other emergency supplies.

“…no matter how well prepared you are,

you probably will never completely convince yourself that ‘it can happen to you’…”, Survival: Training Edition, AF

Manual 64-3, page 1-6

However,

as Survival: Training Edition mentions, you will probably never be able

to fully convince yourself that it can happen to you and if you are not careful

you can unconsciously slip into the “it can’t happen to me” attitude and

from there into “excessive optimism, carelessness, and neglect”. So do your best to remind yourself that it

can happen to you, prepare and anticipate for any emergencies and finally don’t

neglect to file a travel plan or to bring a survival kit and emergency supplies

along with you.

I hope that you continue to enjoy The

Woodsman’s Journal Online and my videos at BandanaMan Productions and don’t forget

to follow me on both The Woodsman’s Journal Online and subscribe to BandanaMan

Productions on YouTube, and if you have questions, as always, feel free to

leave a comment on either site. I announce new

articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds, on Instagram at bandanamanaproductions,

and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch for me.

Notes

1 So

who was Alan Innes-Taylor

|

Charles Alan Kenneth

Innes-Taylor, from the obituary by Philip S. Marshall,

which was published in Arctic,

Volume 37, No. 1, March 1984.

|

Charles Alan Kenneth

Innes-Taylor, who went by the name of Alan Innes-Taylor, experienced the switch

from riverine roads travelled by canoes, steamboats and dogsleds to asphalt

roads and airplanes and he witnessed the change from the heroic age to the

modern age of exploration. He was born

in 1900, in London, England, and his family moved to Toronto, Canada when he

was eight. During World War I, when he

was 17, he enlisted in the Royal Canadian Flying Corps (RCFC) where he learned

to fly: beginning his association flying and aircraft that continues until his

death. Following World War I; he began

to move north, working first with the Canadian Mounties, where he learned

dog-mushing; after that as a miner at the Treadwell Yukon Mine in Keno Hill and

after that as a purser on the steamer the SS Whitehorse.

It was his northern

Canadian and Arctic experience that uniquely qualified him in 1929 to bring

replacement sled-dogs to Admiral Byrd’s BAE I Antarctic expedition. He returned to the Antarctic with Admiral

Byrd in 1933 as the chief of field operations for the BAE II Antarctic expedition.

At the start of World War

II, he was commissioned, by a special act of the American Congress, as a Captain

in the U.S. Army Air Force. He first

helped rescue down air crews from the ice sheets of southeastern

Greenland. Later from mid-1942 to the

end of the war, he trained arctic and mountain troops on how to survive and

operate in these frozen environments.

In 1950, with the start

of the Korean Conflict, he helped to make possible the first commercial air

flights over the North Pole from Stockholm to Tokyo, by the way of Anchorage;

which was pioneered by Scandinavian Airline Systems (SAS) in 1957. He wrote two survival guides for the SAS

aircrews; This is the Arctic: Arctic Survival Guide, a 54-page guide in

1957 and finally, The Arctic Survival Guide, a 137-page survival guide

in 1964. He also invented specialty Arctic

survival gear for them, such as exposure suits and 4-person sleeping bags.

Picture

from the SAS Museum of the 4-person sleeping bag, by Tormund Burn

For more from his obituary

by Philip S. Marshall, click HERE

3 Minister of Supply and Services, Northern Survival,

p. 5

4 Innes-Taylor,

Alan; Arctic Survival Guide, p. 48

5 Innes-Taylor, Alan; Arctic Survival Guide, p. 46

6 Minister

of Supply and Services, Northern Survival, p. 5

7

Ibid

8 Innes-Taylor,

Alan; Arctic Survival Guide, p. 46

9 Innes-Taylor,

Alan; Arctic Survival Guide, p. 48

Sources

Burn,

Tormund; “In the beginning, SAS flew over the North Pole with polar bear rifle

and four-man sleeping bag in the cockpit”, 10/ 28/2018, [Dagbladet, 2019], https://www.dagbladet.no/tema/i-begynnelsen-floy-sas-over-nordpolen-med-isbjorn-rifle-og-firemanns-sovepose-i-cockpiten/70334263,

accessed 9/18/2019

Department Of The Air

Force, Survival: Training Edition, AF Manual 64-3, [Headquarters, US Air

Force, Washington, DC, August 15, 1969], https://books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5Qaea-Z580phmhBGIWOpEb9sVNVKFl2eMbPyfv7ki4p2Zoy6cs7h1CmdXQI0ydjG07PWu6RRNYLtLVCYuecTw2NN4WTAEhAOzNk4TNnzUHc7kP7tsTOrDJ3VK9NEK-NneCrLSICyuWFBMNPcX5ktcJp_VvkWOiUDKjo0k-2FChV7srDVmZ9PH_OOSrcXbuyb5IIy2fCYgUQoVWwECShqfJU9zjSSbvFyxx_xE8Rtx_HUmvwls2pzM2AWkIUgXEGChXtpZx3Mo, accessed 12/12/2018

Innes-Taylor, Alan; Arctic Survival

Guide, [Scandinavian Airline Systems, Stockholm,

Sweden, 1964]

Marshall,

Philip S., Arctic, Volume 37, No. 1, March 1984, http://pubs.aina.ucalgary.ca/arctic/Arctic37-1-84.pdf,

accessed 9/13/2019

Minister of Supply and Services, Northern

Survival, [Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Don

Mills, Ontario, Canada, 1979]

Sunday, September 15, 2019

The Fall Equinox Isn't On September 21st? ©

In

“How to Find Your Way Without A Compass, Part One, Orientation By The Sun”

(HERE), which I wrote earlier this year, and in “Part Three, The Shadow-tip

Method” (HERE); I wrote that in 2019, the Fall Equinox will be on September 23rd. Since I published these articles, I have

received several questions regarding the 23rd as the date of the upcoming

equinox.

Most people wondered if I had mistyped the date, since accepted, common

knowledge is that the Fall Equinox is on September 21st, the Spring

Equinox is on the 21st of March, the Winter Solstice is on December

21st and finally the Summer Solstice is on the 21st of

June. Unfortunately in this case, common

knowledge is only mostly right and the various equinoxes and solstices occur,

either one or two days before or after the 21st, and for the most

part, very rarely on the 21st.

But

why is that, you ask, or at least that is what I asked myself, and so maybe you

asked it too. I didn’t know the answers,

so I did some research, because that is what I do; and here are the “whys” and

the “whens” of our yearly equinoxes and solstices.

Everyone

knows, that on the coming Fall, or as it is more correctly known, September

Equinox1 the Sun rises exactly in the east and sets directly over

the west. But what causes an equinox and

why is it on September 23rd, in 2019, and not on the 21st?

|

Equinox

is from the Latin, “aequinoctium”, meaning “equal night” and there are two

equinoxes every year, one in September and one in March. On these two days, the length of day and

night is nearly equal at roughly 12 hours each, all over the world, and that is

why they are called equinoxes. Also, on

both of them the sun rises in the east directly over the Equator and sets

directly over the Equator in the west; because on these days the tilt of the

Earth’s axis is perpendicular to the Sun’s rays. The equinox occurs the moment the sun crosses

the Earth’s celestial equator, the imaginary plane in the sky that extends

directly out from the Earth’s equator and the exact date and time of this

occurrence varies from year to year. The

March Equinox is both the beginning of spring in the Northern Hemisphere and

the beginning of fall in the Southern Hemisphere and the September Equinox,

which in the Northern Hemisphere is the beginning of fall, is also the

beginning of spring in the Southern Hemisphere.

Most

often the September Equinox falls on either the 22nd or the 23rd.

Less often the September Equinox is on the 21st or the 24th;

the last time it was on the 21st was in the year 1000 and the next

time it will fall on that day is in 2092.

Also, the last time the September Equinox fell on the 24th

was in the year 1931 and the next time will be in 2303.

The

same pattern occurs with the March Equinox, which happens most often on the 20th,

and less often on the 19th.

Solstice

is from the Latin “solstitium” and it

means “sun-stopping”. There are also two

solstices every year, and depending on which hemisphere you are in and they are

both the shortest and the longest days of the year. In the Northern Hemisphere, the June Solstice

is the longest day of the year and the start of summer; while in the Southern

Hemisphere it is the shortest day of the year and the beginning of winter. Six months later, on the December Solstice,

everything is reversed and it is the shortest day of the year in the Northern

Hemisphere and the start of winter and it is the longest day of the year and

the start of summer in the Southern Hemisphere.

Solstices occur when the Sun’s zenith is at its farthest point from the

equator. On the June Solstice, the Sun

reaches its farthest point north at 23.4o north latitude; the North

Pole tilts towards the Sun and the Sun is visible all night from just south of

the Arctic Circle to the North Pole; and the Sun rises to the north of east and

sets to the north of west. Also, south

of the Antarctic Circle, there is no sunlight at all on the June Solstice. On the December Solstice, the Sun reaches its

most southern point at 23.4o south latitude; the South Pole tilts

towards the Sun and from just north of the Antarctic Circle to the South Pole

the sun remains visible all night; and the Sun rises to the south of east and

sets to the south of west. From approximately

the Arctic Circle to the North Pole, the sun remains below the horizon all day and

there is no sunlight at all.

Most

often the June Solstice occurs on the 21st and only slightly less

often it occurs on the 20th.

Similarly the December Solstice, at least for the next 30 years, happens

only on the 21st. So, in the

case of the yearly solstices, common knowledge is mostly correct.

In

the end though, common knowledge is close enough because as Richard Graves

noted when he wrote about equinoxes on page 330 of, The 10 Bushcraft Books,

“…for about two or three weeks either

side of the Equinoctial periods…on any day between March 1st and

April 14th or September 1st and October 14th…”

the Sun rises and sets close enough to the true east-west line to use the

sunrise and sunset to orient yourself.

Similarly, for about two to three weeks on either side of the solstices

the Sun will be close to either its northern or southern zenith. So whether it is the 19th or 24th,

22nd, 21st or 23rd; it doesn’t really matter when

all is said and done.

I hope that you continue to enjoy The

Woodsman’s Journal Online and my videos at BandanaMan Productions and don’t

forget to follow me on both The Woodsman’s Journal Online and subscribe to

BandanaMan Productions on YouTube, and if you have questions, as always, feel

free to leave a comment on either site. I announce new articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds,

on Instagram at bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch

for me.

Notes

1 I accidentally fell into a Northern

Hemisphere-centric bias when I wrote my earlier articles in the “How To Find

Your Way Without A Compass” series. Seasons

are opposite each other on either side of the Equator, and so using the

descriptor, “Fall” for the coming equinox is both inaccurate and a bit of a

misnomer, since the equinox that takes place in September is the Fall Equinox

for the Northern Hemisphere and the Spring Equinox for the Southern Hemisphere. Additionally, using “Spring” for the March

Equinox and “Winter” and “Summer” for the December and June solstices is also incorrect. My apologies to all of my readers, south of

the Equator.

Sources

Grant,

Megan; “Why Isn't The Fall Equinox On Sept. 21? The Earth's Axis & Rotation

Around The Sun Are Incredibly Powerful”, September 21, 2016, https://www.bustle.com/articles/185268-why-isnt-the-fall-equinox-on-sept-21-the-earths-axis-rotation-around-the-sun

Graves,

Richard; The 10 Bushcraft Books, [CreateSpace

Independent Publishing Platform, Middletown, Delaware, USA, December 20, 2017]

“June Solstice: Longest

and Shortest Day of the Year”, [Time and Date AS 1995–2019], https://www.timeanddate.com/calendar/june-solstice.html

“March Equinox - Equal

Day and Night, Nearly”, [Time and Date AS 1995–2019], https://www.timeanddate.com/calendar/march-equinox.html

“Solstices & Equinoxes for Buffalo (2000—2049)”,

[Time and Date AS 1995–2019], https://www.timeanddate.com/calendar/seasons.html?year=2000

“The

September Equinox”, [Time and Date AS 1995–2019], https://www.timeanddate.com/calendar/september-equinox.html

“Winter Solstice – Shortest Day of the Year”, [Time

and Date AS 1995–2019], https://www.timeanddate.com/calendar/winter-solstice.html

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)