You are “misplaced” in the woods and

this is your bed tonight, picture by the author.

So,

it happened! It had to happen to you

eventually, you know; it happens to everyone eventually. Maybe you got turned around and now you are

“misplaced”, and you have no idea on how to get back to where you were. Maybe, you slipped and fell, and now you are

too injured to get out of the woods by yourself. Or, maybe the Sun is going down behind the

trees and you have less than two of daylight left. What do you do now?

You

need to find shelter, of course! But

what should you look for?

Graphic by the author.

Summer

or winter, it doesn’t matter, the elements are your worst enemy; humans can’t

survive heat or cold, wet or wind for long without a shelter. Because protecting yourself from the elements

means different things in different climates and at different times of the

year, the type of shelter that you build will depend on where and when you are

building it. It is true, that a lot

could, and has, been written about how to build a shelter, however today, I am

writing about things that you should think about before, and as, you build your

shelter.

Location,

location, location…and the 5 W’s

Whenever

you set up a campsite in the wilderness, you should always consider the 5 W’s,

wind, water, widow-makers, wood and wildlife, before you choose a location.

Wind

You

must treat wind with respect and plan for it when you choose the location of

your shelter, because in a survival situation wind can be your enemy and kill

you fast if you let it. Wind and wind-chill

it can lower the “real-feel temperature” and bring on hypothermia; it can suck

the moisture out of you and bring on dehydration, or it can blow down branches

and trees on you and squash you flat. On

the other hand, wind can blow mosquitos and other bugs away from you and your

campsite. So, what type of winds are

there?

Prevailing winds worldwide, from Moon

Joon Kim

Prevailing

winds are, according to the Oxford dictionary, “a wind from the direction

that is predominant at a particular place or season”. It is always important when you travel or

camp in the wilderness to know the usual wind direction, when canoeing it can

help you stay in the calm water on the sheltered lee side of the shore or if

you put your camp on the windward shore, it can help blow the bugs away from

your camp. It is important to remember

that prevailing winds are not constant all day long, as Alan Innes-Taylor noted

on page 53, when he wrote of prevailing winds in the Arctic Survival Guide:

“Fair weather winds usually decrease at night”. In Algonquin Provincial Park and much of

northeast Canada and the United States, fair weather winds usually blow from

the northwest to the southeast during the day.

Windward and leeward sides of hills

or mountains, modified from Eliane Truccolo

Offshore, onshore and valley winds,

modified from Eliane Truccolo

Onshore winds, from Fig. 2-10, Aviation

Weather Student Guide

|

Offshore winds, from Fig. 2-11, Aviation

Weather Student Guide

Offshore, onshore and valley winds are all very similar and are both generated by the daily warming and cooling of the

land. The differences in the specific

heat of land and water causes the land to warm and cool more quickly than water,

during the day this causes warming and rising air over the land and descending

or cooling air over the water resulting in an onshore or sea breeze. At night the process reverses with the land

cooling quicker faster than the water, which cause descending cool air over the

land and rising warm air over the water and creates an offshore of land

breeze. Onshore breezes seldom penetrate

far inland, but they are usually stronger than offshore breezes.

Mountain and valley winds, from Fig.

2-12, Aviation Weather Student Guide

In

the daytime mountain slopes and hillsides are heated more quickly by the Sun

than valley bottoms, and these slopes warm the surrounding air through

conduction. This warmed air rises and then

later cools and sinks back down towards the valley floor, forcing the air from

the valley floor up the mountain or hillside, completing the cycle of

circulation and creating an upslope and up valley wind. At night the air in contact with the mountain

slope or hillside cools faster than the valley bottom because of outgoing

terrestrial radiation and this denser cool air flows down slope and down valley

and forces warmer valley bottom air upwards, creating a circulation pattern and

downslope and down valley winds.

| Excerpts from the Arctic Survival Guide, p. 53, by Alan Innes-Taylor |

All

of this is important, because you want to face your shelter so that the front

is perpendicular to the general flow of the wind.

Water

and Widow-makers

The second and third of the 5 W’s are water and

widow-makers. While you want to be near

drinking water, setting up your shelter near that babbling brook is often a bad

idea, as a storm far upstream can quickly turn that tame stream into a raging

torrent and wash you away. Also, you

should look for a level area half-way between the summit of the hill and the valley

bottom, as the cold night air collects in low spots and valleys and the summits

of hills are always cold. It is

often significantly warmer half-way up a hillside, between the crest of the

hill and the valley bottom and far safer from flooding. Always look up and around your planned campsite

and make sure there a no dead trees, snags or widow-makers stuck in the

branches above you, just waiting for the right wind to come crashing down on

you. And lastly, don’t shelter under the

tallest tree in the forest, it is a lightening rod! If possible, shelter in a grove of equal

sized trees. Also avoid hill-tops and

exposed cliff faces can also attract lightening, so don’t shelter at the base

of the tallest cliff in the area or on the top of the hill.

Wood

An excerpt from “How Not To Get

Lost”, by Charles Elliott

The

fourth of the 5 W’s is wood, the area that you choose for your campsite should

have plenty of firewood and building materials, such as leaves, boughs, bark,

branches, etc.

Wildlife

The

last of the 5 W’s is wildlife, be careful of setting up your shelter on game

trails, near swampy areas that breed mosquitos or in a rock shelter that is

already called home by one of the locals.

And

now that you have some ideas on where to build your shelter, the first and most

basic shelter you need, is the one that will insulate you from the cold, cold

ground. If you have ever slept directly on

the ground, when the night-time temperatures drop close to freezing, as I have

once upon a time, you will know how painful it is as the ground sucks the heat

out of your kidneys! I can tell you from

personal experience that, insulation between you and the ground is your

friend. You should always build a

shelter bed before you build any other shelter. Mors Kochanski, a well-known survival expert,

wrote that shelter beds or emergency bough beds should have a compressed

thickness of at least 4 fingers or about 3-1/2 inches of dead air space between

you and the ground or snow as insulation.

Earlier in 2019, I experimented with making a bough bed and discovered

that a 28 inch (72 cm) high pile of boughs compressed down to 18 inches (46 cm)

of insulation when I sat down on it.

Shelter beds insulate your sleeping body from the cold ground and make

you more comfortable and allow you to sleep better. For more on shelter beds, read “Making an

Emergency Bough Bed”, HERE and watch “Building An Emergency Bough Bed”, HERE.

There

are two types of shelters, found shelters and built shelters, and of most are

reflector shelters. Found shelters are

exactly as they sound, shelters that you find in the wilderness and they can be

a rock shelter, cliffside or big boulder, a blown down log or an uprooted tree;

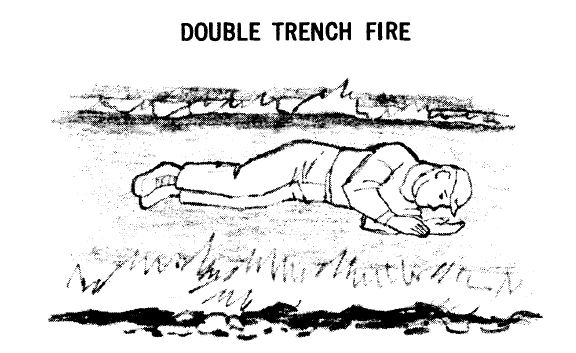

or simply a large tree that you can lean against during the night. Built shelters are lean-to’s, debris beds or

double trench fires, these last two are the only two that are not reflector

shelters. Reflector shelters are any

open or roofed shelter where you are between the reflector and your fire. Lean-to’s or debris shelters take more time

and energy to build but, are the most weatherproof of shelters. Below are some examples of shelters that you

could find or build in an emergency.

|

| An illustration of a found, reflector type of shelter from “But If You Do Get Lost”, Kenneth Cole, p. 90 |

A blown down tree and upturned root ball, a found, reflector type of shelter, photo by the author

Looking out from underneath a rock

shelter, an example of a found reflector type of shelter, photo by the author

|

| An illustration of a built reflector type of shelter from Arctic Survival Guide, by Alan Innes-Taylor, p. 54 |

|

| An illustration of a built reflector type of shelter from Arctic

Survival Guide, by Alan Innes-Taylor, p. 54 |

|

An illustration of a built reflector

type of shelter from Arctic Survival Guide, by Alan Innes-Taylor, p. 55

An illustration of a built shelter

which may or may not be a reflector type of shelter from “But If You Do Get Lost”,

by Kenneth Cole, p. 90

An illustration of a built

non-reflector type of debris shelter, from Outdoor Survival Training For

Alaska’s Youth, by Dolly Garza

An illustration of a built

non-reflector type of shelter from “But If You Do Get Lost”, by Kenneth Cole,

p. 90

This

is a thumbnail sketch of building or finding a shelter in a survival emergency.

Hopefully you will never have to build

or find one in a real emergency, however they are a lot of fun to find or build

for practice.

An upturned root ball reflector

shelter, nighty-night, photo by the author.

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and my videos at

BandanaMan Productions and don’t forget to follow me on both The Woodsman’s

Journal Online and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube, and if you

have questions, as always, feel free to leave a comment on either site. I announce new articles on Facebook at Eric

Reynolds, on Instagram at bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds,

so watch for me.

Sources

Cole,

Kenneth M., Jr.; “But If You Do Get Lost”, Outdoor USA: 1967 Yearbook of Agriculture [United

States Department of Agriculture, United States Government Printing Office,

Washington, DC, 1967] p. 89-91, https://archive.org/stream/yoa1967/yoa1967_djvu.txt,

accessed 6/16/14

Elliott,

Charles; “How Not To Get Lost”, Outdoor USA: 1967 Yearbook of Agriculture

[United States Department of Agriculture, United States Government Printing

Office, Washington, DC, 1967] p. 87-89, https://archive.org/stream/yoa1967/yoa1967_djvu.txt,

accessed 6/16/14

Garza,

Dolly; Outdoor Survival Training For Alaska’s Youth: Student Manual,

[Alaska Sea Grant College Program, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 1998], p. 13,

https://www.nwarctic.org/cms/lib/AK01001584/Centricity/Domain/507/OutdoorSurvivalTraining-StudentManual.pdf

, accessed 12/4/2017

Kim,

Moon Joon; “Essays on Long-Range Transport of Air Pollution and Its Health

Outcomes”, [Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North

Carolina, 2017], p. 4, https://repository.lib.ncsu.edu/bitstream/handle/1840.20/34686/etd.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y,

accessed 9/28/19

Kochanski

Mors L.; Bush Craft, [Partners Publishing, Edmonton, AB., 2014] p.174

Aviation Weather Student Guide, “Atmospheric

Mechanics of Winds, Clouds and Moisture, and Atmospheric Stability”, http://navyflightmanuals.tpub.com/P-303/Sea-And-Land-Breezes-43.htm,

[Integrated Publishing, Inc.], p. 2-11 to 2-13, accessed 9/28/19

Truccolo,

Eliane; “Assessment of the wind behavior in the northern coast of Santa

Catarina”, Revista Brasileira de Meteorologia, Vol 26, 3, September 2011,

p. 451-460, http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102-77862011000300011,

accessed 9/28/19

Vliet,

Russ; A Manual of Woodslore Survival, [Philmont Scout Ranch, Cimarron,

New Mexico, 1950], p. 7-8