|

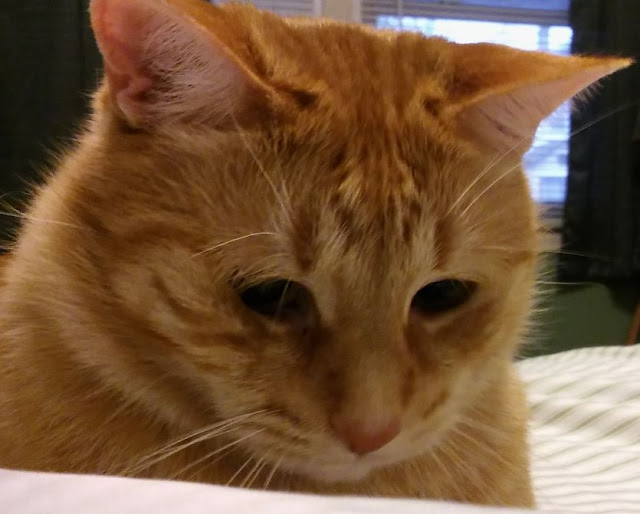

| Mountain lion print found near Red House, Allegheny State Park, NY

during November 2017. Picture by the

Author |

The truth and the cats are out there…Do you believe?

I grew up hearing stories about mountain lions in

western New York: when I was little, I remember my Father telling me a story

that took place when he was a young boy, shortly after World War II. Some cousins of my Father’s foster family,

who lived outside of Forestville, New York, told him about a panther that had

been heard, at night, in the hills, south of the village, and the hunt that

took place looking for it. Of course,

they didn’t find an eastern mountain lion, because as everyone knows, cougars,

catamounts, painters, panthers, or just plain mountain lions, which are all

names for the same animal, and had been extinct since the early years of the 20th

century on the east coast of North America.

Fast forward to 2008, it was a warm early fall day and

we had decided to take a trip to the “Hanging Bog”, which is a large beaver

pond, in the hills, near Rushford, New York.

We thought it would be a good day to do some canoeing and exploring and

my youngest son, who was four at the time, had never been in a canoe before. We canoed to shore on the far side of the

lake and as I stepped out, I saw “it”.

“It” was a large paw print, the size of a baseball, without any claw

marks, that was just starting to fill with water. Someone had watched us bring the canoe to the

shore and that someone was a cougar. I

quickly scanned the trees around the landing, to see if there was a large cat

above me in the branches. I loosened the

small axe that I always carry when I wander in the woods, which was under my

belt, in the small of my back. I didn’t

see the cougar, just a lonely paw print rapidly filling up with water, at the

edge of swampy lake. Oh, and of course,

just as these things always go, I didn’t have a camera with me.

|

| Mountain lion print found near Red House, Allegheny State Park, NY

during November 2017. Picture by the

Author |

It was a sunny, early November day in 2017, and we had

decided to take a hike near Red House, in Allegheny State Park, in southwestern

New York State. We were hiking along the

top of a ridge that separated two narrow, steep-walled valleys with small

streams down their centers. It had

snowed the night before, only about a quarter of an inch, and it was still

below freezing, although the sky was clear and the sun was bright, when I saw

“it” again. Again, “it” was a single,

large paw print without any claw marks, boldly stamped in the snow, as if a

large cat had stepped over the path.

This time I had a camera, and I took a picture, thankfully, just before

a woman with a small herd of yappy dogs came around the bend of the trail and

trampled all of the evidence.

In 2008, no one believed that I saw, what I had seen,

because of course, there are no cougars left on the east coast of North

America, except in the very south of Florida, which is a long way away from

rural western New York. However, I knew

what I had seen.

In 2011, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concluded that

there are no native populations of mountain lions east of the Mississippi, except

in Florida, and any that are seen, are escaped or released pets. The native eastern mountain lions, as a

subspecies (puma concolor couguar), was considered to have gone extinct in the

early years of the 20th century.

Shortly after the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services

announcement regarding the extinction of the native eastern mountain lions, came

the news in 2011, that a young male cougar that had been hit by a car on Wilbur

Cross Parkway, in Milford, Connecticut, only 70 miles from New York City. Scientists, using DNA tests, determined that

this cougar was from South Dakota, and he had travelled more than 1,800 miles,

through Michigan, into Canada, crossing back into New York State near the

western edge of the Adirondacks, before travelling southeast to his fateful encounter

with an SUV, on the parkway.

After, the South Dakota mountain lion was killed on

the parkway in Connecticut, in 2011; migratory western mountain lions were

added to the mix. Officially, there is

not a breeding population of mountain lions east of the Mississippi and today,

if you see a mountain lion in the woods, you have seen a migratory western lion

or an escaped or released pet.

Tracks

and Scat

Most likely, you will never see a mountain lion in the

woods; however, you might see evidence of its passing, either tracks or scat. So how can you tell if those tracks you have

found belong to a mountain lion? The

first clue is whether there are claw marks or not. Canine tracks usually display claw marks,

while cat tracks do not; also canine tracks tend to be oval and are longer from

heel to toe than they are wide. Additionally,

cat tracks often display a leading toe, which is a toe that sticks out further

than the rest, while with dog tracks the two front toes are side by side. The second thing to look for is the size of

the track and the size of plantar or heel pad; mountain lion tracks are quite

large, up to five inches in diameter, although on average they are closer to

three inches in diameter. The average

male mountain lion will leave tracks that are four inches wide, while the

average female mountain lion will leave tracks that are up to three and a half

inches wide. In addition, you might be

able to determine the sex of the mountain lion by the size of its plantar pad; the

average adult female mountain lions have a plantar pad that is less than two

inches wide, while the average male mountain lion will have a plantar pad that

is greater than two inches in width. The

heel pads of cats are larger than the small, two lobed, triangular pads of dogs

and the three lobed pad looks like an “M”. And, the last clue is whether an “X” drawn between the first and fourth

toe pad, crosses through the heel pad or not.

If the “X”, when drawn, does

not cross over the rear pad then it is a dog track, while if it does cut

through the rear pad, it is a cat track.

|

| (L) Coyote track, actual size, Animal Tracks: Roger Tory Peterson

Field Guide, Figure 46, p. 95 and (R) Mountain lion track, scaled to actual size, Figure

52, p. 110. Note the lack of claw marks

on the Mountain lion track and how an X drawn between the first and fourth toe

pad, crosses through the heel pad. |

|

| Mountain lion print found near Red House, Allegheny State Park, NY

during November 2017. Picture by the

Author |

So, I used these tests on the track that I found near

Red House in November 2017: unfortunately, because the leaf under the rear pad

makes it difficult to see the outline of the heel, this isn’t the best track to

analyze. However, the size, round shape

and the absence of any claw marks, makes me believe that this is not a dog’s footprint

and is most likely a mountain lion’s paw print.

|

| Animal Tracks: Roger Tory Peterson Field Guide, Figure 57, a.

Tracks in mud; b, c, d., Walking or trotting gates; e. Mountain lion wallowing

in snow; f. Tracks in snow, showing foot drags; g. Leaping gait in snow,

showing tail marks; p. 118-119 |

Instead of tracks, you might find scat. If you do find scat, you will notice that it

is full of hair and bits of bone, however, since members of the cat family tend

to cover their dung, scat is not often found.

If found, the scats from large cats can be hard to distinguish from

those of dogs or coyotes. Cat scat is

more segmented, by constrictions, than those of dogs are, but the best clue

would be that scat is covered or that there are claw marks surrounding the dung

pile.

|

| Animal Tracks: Roger Tory Peterson Field Guide, Figure 53, Mountain

lion scat, p. 111 |

Mountain

Lion Facts

· Mountain

lions have a wide range throughout the western United States and both their

population and range are increasing.

They can easily travel 20 to 30 miles a day, hunting an eating along the

way.

· A

mountain lions range depends on the amount of available food and can be from 10

square miles to 370 square miles.

· Mountain

lions weigh an average of 130 to 140 pounds, with male lions weighing an

average between 115 to 160 pounds and female lions weighing between 75 and 105

pounds.

· Mountain

lions live on average 12 years in the wild and in captivity have lived to 25

years.

· Mountain

lions are solitary animals and are seldom seen, they prefer remote, wooded

areas: searchers generally have to content themselves scat, tracks and the

remains of kills and food caches.

· Mountain

lions need eight to ten pounds of meat a day to survive and experts estimate

that a mountain lion kills one deer every nine to fourteen days. In general, mountain lions prefer deer, when

they are not eating deer; their diet includes elk, porcupine, small mammals,

livestock or pets.

· Most

mountain lions will avoid a confrontation, so keep your distance and make sure

it has an open escape route. If a

mountain lion is angry or anxious, it will crouch down and thrash its tail,

stare at you and keep its body low to the ground. Immediately before an attack, a mountain

lion’s ears will flatten down against its head and its rear legs will pump.

In the end, does it matter whether the lion you saw,

or whose tracks you found, was a migrating western mountain lion, an escaped or

released pet, or a relic of the original eastern mountain lion population? Do you know what to do if you have a close-range,

surprise encounter with one, who seems angry or anxious? Worse, do you know what to do if a mountain

lion appears to be following you at a distance and staring intently at you: in short,

it is stalking you?

|

| A portion of the photo titled “seen mountain biking at Skeggs today”, by

Steve Jurvetson |

How

to Avoid an Encounter

· Since

mountain lions are nocturnal, be especially cautious when moving around at night.

· To

avoid an encounter with a mountain lion, make noise so that the mountain lion

knows that humans are in the area and hike in groups.

If

You Encounter a Mountain Lion

Most mountain lions will avoid a confrontation with

humans, so stay calm. If the lion is

angry or anxious, try to identify why it is upset. Are you between a female and her kits? Are you near its den or its kill?

· With

mountain lions, it is all about being seen as prey or being seen as a threat

· Always

and at all times maintain eye contact, while you slowly back away giving the

lion an avenue to escape. Do not bend

over, as you will lose eye contact and you will look like a four legged prey

animal.

· Never

turn your back and never EVER run away from a lion! If you do, you will trigger the cat’s

predatory instincts.

· Stand

tall, wave your arms or hold your coat open, yell and throw sticks and stones

at it. If you are in a group, stand side

by side so that you appear bigger. If

you have children, put them behind you or hold onto them.

If

You Are Attacked

· If

you have bear spray, use it. If someone

is being attacked and you have bear spray, spray both the lion and the person

being attacked if necessary.

· Do

not play dead, fight back! Playing dead

means that you will end up dead for real.

Fight back because 75% of those attacked by mountain lions survive. Mountain lions kill people by biting the back

of the neck and snapping the spine, by biting through the skull, or by biting

the throat and suffocating their victim.

If you are bitten, stick your finger into the lion’s eye.

· If

you are with a group, fight the mountain lion as a group.

If

You Are Being Stalked

· If

a mountain lion is following you at a distance and watching you intently, it is

probably trying to determine if you are or are not prey.

· Stand

tall, wave your arms or hold your coat open, yell and throw sticks and stones

at it. If you are in a group, stand side

by side so that you appear bigger. If

you have children, put them behind you or hold onto them.

· Make

sure that you have scared it away before, immediately leaving and reporting the

situation to the proper authorities.

Sources

Lancaster, Laura; “Fight or Flight?” [American

Survival Guide, December 2015, ] p 77-81

Murie, Olaus J., Animal Tracks: Roger Tory Peterson

Field Guide, [Easton Press, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1974] p.110-111, 118-121