|

A murder of crows, perching on an old building. Spooky!

Photograph by the author.

For the sound of a carrion crow, corvus corone,

click HERE,

from “The call of a Carrion Crow recorded in a garden at

Culver, near Exeter, Devon, England”, Wikimedia.

It

is almost Halloween and the crows are flocking together for winter. But what do you call

three or more crows gathered together?

Why

a murder of crows, of course!

“Hmmm...that

is a rather unusual phrase for a flock of birds”, you might say, “why is

it called that”?

That

is a great question and since I didn’t know the answer, I did what I always do,

and I did some research: here is what I found.

|

An

excerpt from The Boke of Saint Albans, Dame Juliana Berners, 1486 as reprinted

in 1901, page 114.

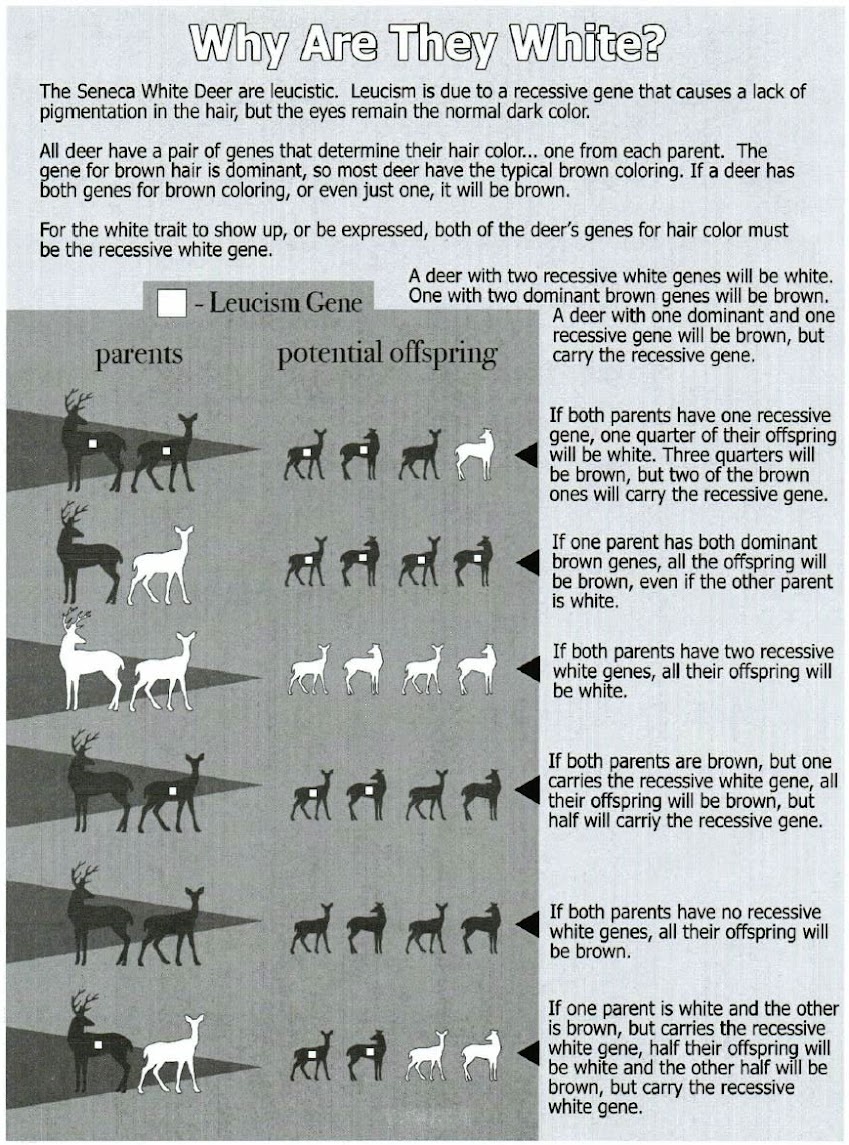

A

murder of crows, or as it was spelled in the late 1400s and early 1500s, “a

Morther of crowys”; is an old phrase that was used to describe a group of three

or more crows1. This phrase

first appeared in late medieval English books of venery2, the

earliest surviving examples of which were published in 1476 and 14863.

Some

sources say that this phrase fell out of use during the 1500s and did not

reappear until the 20th century.

In 1909 John Hodgkins, a member of the Folk Lore Society, wrote a 182

page explanation of the meaning of the various phrases, including “a Morther

of Crowys”, which were found in The Book of Saint Albans and other

manuscripts on venery: a murder of crows was back!

There

are two schools of thought on why this particular phrase was used to describe a

flock of crows. The first is that crows,

since they are scavengers, would have been associated with gallows,

battlefields, murdered corpses and other scenes of violent death.

And

second, during the late medieval period in England and extending until the

early 19th century, when the statutes were repealed, it was the duty

of every law abiding person who discovered a felony or had a crime committed

upon them to raise the “Hue and cry”.

Anyone hearing this alarm was legally bound to join in and pursue and

apprehend the offender. Perhaps the late

medieval writer who first coined the phrase “a Morther of crowys”, thought

that the clamor that a raucous mob of crows makes, when they chase an owl or a

hawk was similar to the “Hue and cry”?

Once upon a time, I saw a mob of really upset crows, in full cry,

ganging up on an owl and it sure sounded as if they were screaming bloody

murder!

Personally,

I think that both of the reasons are equally as likely and both probably played

into the tongue-in-cheek description of a flock three or more crows, but in the

end we will never really know.

One

thing is certain though, those late medieval English woodsmen knew the

difference between crows and ravens, and felt that it would be an unkindness to

confuse a raven with a crow. Maybe that

is why a flock of three or more ravens is called “an unkindness of Ravens”! In case you are confused on how to tell the

difference between a crow, and a raven, read “And A Raven Came Calling…©”, HERE.

Happy

Halloween!

|

“Carrion crows on a trash in Annecy on December 30th,

2011”, by PierreSelim, on Wikimedia, HERE.

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and look for me

on YouTube at Bandanaman Productions for other related videos, HERE. Don’t forget to follow me on both The

Woodsman’s Journal Online, HERE,

and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube. If you have questions, as always, feel free

to leave a comment on either site. I

announce new articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds, on Instagram at

bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch for me.

That

is all for now, and as always, until next time, Happy Trails!

Notes

1

Three or more crows is a murder, and today people say that two crows together is

an “attempted murder”. The reason three

crows is a murder and two are simply just two crows, could be because of an old

English and Scottish border ballad called “The Three Ravens”, in which three

ravens are discussing why they can’t have a fallen knight for breakfast. This version of the ballad was first printed

in 1611, but it is probably older than that.

A rather darker version of this ballad is the Scottish ballad called

“Twa Corbies”, or Two Crows, in which the two crows are successful in making a

meal of the fallen knight, this version probably dates from the 18th

century and was first printed in 1812.

From

Scottish Country Dancing, “The Three Ravens: English Folk Ballad – Anonymous”

2

Venery is an archaic word for hunting, particularly as practiced by the late

medieval English nobility.

3 the

Hors, the Shepe, & the Ghoos, was originally printed by Caxton, circa

1476, and it was reprinted by the Roxburgh Club in 1822. The Boke of Saint Albans, which

contains a section called “The Compaynys of beestys and fowles”, was originally

published in 1486.

Sources

Berners, Dame Juliana; The

Boke of Saint Albans, [Reprinted by Elliot Stock, Paternoster Row, London,

1901], page 114, https://archive.org/stream/bokeofsaintalban00bernuoft#page/114/mode/2up, accessed October 16, 2020.

BirdSpot, “Why Is A Group Of Crows Called A Murder?”, [©

2020 BirdSpot], https://www.birdspot.co.uk/bird-brain/why-is-a-group-of-crows-called-a-murder, accessed October 18, 2020

The British Library Board, “The call of a Carrion

Crow recorded in a garden at Culver, near Exeter, Devon, England”, April 2,

1961, Wikimedia, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8a/Carrion_Crow_%28Corvus_corone%29_%28W1CDR0001425_BD18%29.ogg,

accessed October 20, 2020

Grammarphobia;

“A murder of crows”, January 18, 2008, [© 2020 Grammarphobia], https://www.grammarphobia.com/blog/2008/01/a-murder-of-crows-2.html,

accessed October 18, 2020

Hodgkin, John; Proper

Terms, Transactions of the Philological Society, 1907-1910, [Kegan Paul,

Trench, Trübner, & Co., Ltd., London, 1909], pages 46-47, https://books.google.com/books?id=I-gzAQAAMAAJ&pg=RA2-PA127&dq=%22morther+of+crowys%22+%22Transactions+of+the+Philological+Society%22&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwigvPuhtb7sAhWrnOAKHcBSCocQ6AEwAHoECAAQAg#v=onepage&q&f=false, accessed October 18, 2020

PierreSelim,

“Carrion crows on a trash in Annecy on December 30th, 2011”, December 30, 2011,

Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Annecy_-_Corvus_Corone_-_20111230_-_02.JPG,

accessed October 20, 2020

Scottish

Country Dancing; “The Three Ravens: English Folk Ballad – Anonymous”, https://www.scottish-country-dancing.com/three-ravens.html,

accessed October 19, 2020

The

Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, “Hue and cry”; February 23, 2012,

[Encyclopedia Britannica, 2020], https://www.britannica.com/topic/hue-and-cry,

accessed October 18, 2020