This is the ninth in a series of eleven articles on

the top ten wilderness survival skills, things you should know before you go

into the wilderness. To read the

previous article go HERE

– Author’s Note

The Number

Nine, Top Ten Wilderness Survival Skill: Rope, Knots and How to Tie Them

The

number nine, top ten wilderness survival skill on my list is, knowing how to tie knots.

If

you don’t have any rope or string and you can’t tie knots in a wilderness

survival situation, you are going to have a hard time building a shelter,

hanging up a bear-bag, or even putting up a clothesline.

Do you have

any...rope?

|

Shelter supplies that I keep in the back pocket of my survival vest or survival PFD, 1) paracord, 18 feet (5.5 meters); 2) a knit hat, clothes are portable shelter; and 3) two heavy duty contractor grade trash bags, all of which weigh 12 ounces (340 grams). For more on the survival supplies I carry read “A Survival Kit, Your Ace in the Hole ©”, HERE. Photograph by the Author.

Rope

or string of any type is difficult to find or make for yourself in the

wilderness and that is why you should always carry some. Personally, I always wear a BanadanaMan

Emergency Bracelet, which contains 174 inches (442 cm) of string on my wrist

when I am out in the wilderness, and I always keep 18 feet of paracord in the

back pocket of my survival vest or survival PFD. Both will make building an emergency shelter much,

much easier.

But first,

some words about rope...

|

An excerpt from Survival, FM 3-05.70 (FM 21-76), page G-3.

Also,

before we start talking about tying knots, we need to talk about things like loops,

bights, the running-end of a rope.

A

bight is a simple bend of rope, which does not cross itself, while a loop is

formed by crossing the running end over or under the standing end to form a

ring or circle in the rope. The running

end of the rope is the free end of the rope, this is the part of the rope you

are using to tie the knot. The standing

end of the rope is the rest of the rope beyond the running end and the working

end is the part of the rope that is attached to the thing that is being rigged

or hauled. A pig tail is the part of the

running end of the rope that is left over after tying a knot and it shouldn’t

be more than 4 inches (10 cm) long, to conserve rope and prevent interference. A turn in a rope is a loop around something

like a tree or a branch, with the running end continuing in the opposite

direction to the standing end, while a round turn continues to circle and exits

in the same direction as the standing end1.

Knots,

stress points and rope failure...

|

The Camper’s Knot Tying Card Game, by Marco Products

While

we are talking about knots, did you know that a knot in a rope will put stress

on a rope and can cause it to break?

Well,

it can! When you tie a knot in a rope it

immediately loses between 25% to 60% of its original strength, since the knot

causes a stress point where the rope fibers on the outside of the of the knot are

stretched more and the strands on the inside of the knot are stretched less and

might even be compressed. The

combination of these stresses can cause a rope to fail and break at the knot.

Ten

Essential Knots and how to tie them...

|

An excerpt from Survival, FM 3-05.70 (FM 21-76), page G-3.

Everyone

knows how to tie an overhand knot, it is an important knot that is often used

as a finishing knot, but can you tie a sheet bend, a taut-line, or an alpine

butterfly knot?

People

always tell me that they just can’t tie knots, but what the problem really is

though, is a lack of practice. If you

want to be good at knots, make up your mind to learn the ten essential knots,

and then practice, practice, practice!

The six basic knots...

There

are six basic knots that are considered must know wilderness knots, the square

knot, the sheet bend, the taut-line hitch, two half hitches, the lark’s head,

and the bowline.

|

An excerpt from Knots and How to Tie Them, by the Boy Scouts of America, page 10.

The

square knot or reef knot is one of the most easily remembered of knots, and

when it is used as a binding knot to tie a parcel together or to knot together a

neckerchief or cravat, it can’t be beat.

However, when it is used as a bending knot to tie together two different

sizes of ropes or to tie together a rope that is stiffer or more slippery than the

other one, it will come apart. So,

beware!

|

An excerpt from Knots and How to Tie Them, by the Boy Scouts of America, page 11.

The

sheet bend is a true bending knot and can be used to tie together two ropes of different

sizes or stiffnesses, and in form, according to The Ashley Book of Knots,

it is the same as the weaver’s knot, and is also known as the simple bend, the

bend, the ordinary or common bend, or, to distinguish it from the double sheet

bend, the single bend.

|

An excerpt from Knots and How to Tie Them, by the Boy Scouts of America, page 16.

Taut-line

hitches are a knot that I use whenever I put up tents, tarps, or clotheslines,

it is one of my go-to knots!

|

A good use of taut-line hitches, a tarp set up along the shore of Rock Lake, Algonquin Provincial Park, August 2019. Photograph by the Author.

|

An excerpt from Knots and How to Tie Them, by the Boy Scouts of America, page 18.

The

bowline is also called the bowling or bolin knot2 and is identical

in form to the sheet-bend, but instead of joining two different ropes, it joins

the free end of the rope to itself, making a loop.

|

An excerpt from Knots and How to Tie Them, by the Boy Scouts of America, page 19.

Imagine you are up to your waist in the water or in a bog and someone throws you a rope. You grab the rope, and tie a bowline around your waist, because you know the knot won’t slip and you can be pulled back to solid ground! To watch a video on how to tie a bowline around your waist, one-handed, go HERE.

|

An excerpt from Knots and How to Tie Them, by the Boy Scouts of America, page 13.

Two

half hitches are my other favorite knot, I frequently use it to tie a canoe’s

painter to a dock post if I am using a civilized landing. In fact, as mentioned in The Ashley Book

of Knots, during the era of sailing ships it was frequently used to tie a

ship to a wharf, and as sailors used to say, “Two half hitches will never

slip”, by Admiral Luce, and “Two half hitches saved a Queen's Ship”,

by Anonymous3.

|

The lark’s head knot, from Knotting and Splicing Ropes and Cordage, by Paul N. Hasluck, page 47.

The

lark’s head is also known as the cow hitch, the lanyard hitch, the dead-eye

hitch, the stake hitch, or the ring hitch; and when it is tied in a bight or a loop

of a continuous rope circle it is called a strap or bale sling hitch4. This is another of my favorite knots and I

use it to hang things by their lanyard or when I am putting up a tarp and I

want to make a “magic grommet”5, to secure the edges of a

tarp to a ridgeline.

|

How to use a lark’s head to make a “magic grommet”, photograph by the Author.

The four advanced knots...

However,

there are four other knots that are also considered must know, advanced,

wilderness knots: the clove hitch, the double-sheet bend, the timber hitch, and

the alpine butterfly.

|

An excerpt from Knots and How to Tie Them, by the Boy Scouts of America, page 14.

According

to The Ashley Book of Knots, “There is no such thing as a good

general utility knot, although ashore the CLOVE HITCH comes very near to

filling the office of a general utility hitch”. The clove hitch is easily remembered and can

be quickly tied.

|

An excerpt from Knots and How to Tie Them, by the Boy Scouts of America, page 11.

The

double sheet bend is also known as the double weaver’s knot and just like the

sheet bend is used to secure two ropes or strings. The double sheet bend is not any stronger

than the sheet bend, but it is more secure.

|

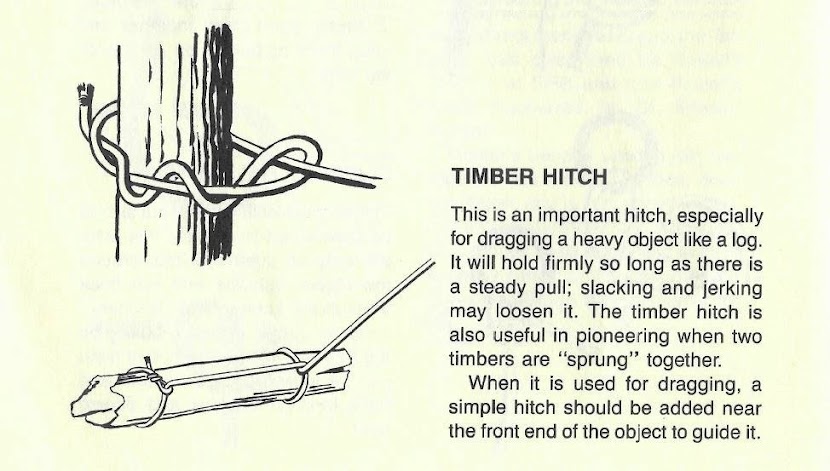

An excerpt from Knots and How to Tie Them, by the Boy Scouts of America, page 14.

The

timber hitch is also called the countryman’s or lumberman’s knot and is an old

knot. According to The Ashley Book of

Knots, it was mentioned in the 1625 Manuscript on Rigging, in in

Denis Diderot’s 1762, Encyclopedia, and in David Steel’s 1794, Elements

and Practice of Rigging and Seamanship.

The

turns around the rope should always be “dogged”, wrapped, or turned, with

the lay or twist of the rope. Three

turns around the rope are usually enough6.

|

An excerpt from Knots and How to Tie Them, by the Boy Scouts of America, page 20.

The

alpine butterfly knot is also called the butterfly loop, the lineman's loop, or

the butterfly knot and used to form a fixed loop in the middle of a rope. It can be used to make loops for handholds or

footholds and is used by rock climbers to make loops in a rope for a

carabiner. It can also be used to

isolate a worn section of rope

One

Essential Lashing...

|

An excerpt from Knots and How to Tie Them, by the Boy Scouts of America, page 30.

Everyone

that journeys through the wilderness should learn how to tie a tripod lashing,

because with this lashing you can make a lean-to or a teepee shelter, a tripod

to hang a pot over the fire on, or many other handy things.

Don’t forget to come back next week and read “Ten Essentials of Winter

Camping ©”, where we will talk about how to camp in the winter wilderness and

stay warm and safe.

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and look for me

on YouTube at BandanaMan Productions for other related videos, HERE. Don’t forget to follow me on both The

Woodsman’s Journal Online, HERE,

and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube. If you have questions, as always, feel free

to leave a comment on either site. I

announce new articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds, on Instagram at

bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch for me.

That

is all for now, and as always, until next time, Happy Trails!

Notes

1

Other rope and knot terms are as follows:

•

Dressing the knot. The orientation of

all knot parts so that they are properly aligned, straightened, or bundled. Neglecting this can result in an additional

50 percent reduction in knot strength. This term is sometimes used for setting

the knot which involves tightening all parts of the knot, so they bind on one

another and make the knot operational. A

loosely tied knot can easily deform under strain and change, becoming a

slipknot or worse, untying.

•

Fraps. A means of tightening the

lashings by looping the rope perpendicularly around the wraps that hold the

spars or sticks together.

•

Lashings. A means of using wraps and

fraps to tie two or three spars or sticks together to form solid corners or to construct

tripods. Lashings begin and end with

clove hitches.

•

Lay. The lay of the rope is the same as

the twist of the rope.

•

Whipping. Any method of preventing the

end of a rope from untwisting or becoming unwound. It is done by wrapping the end tightly with a

small cord, tape, or other means. It should be done on both sides of an

anticipated cut in a rope, before cutting the rope in two. This prevents the rope from immediately

untwisting.

•

Wraps. Simple wraps of rope around two

poles or sticks (square lashing) or three poles or sticks (tripod lashing). Wraps begin and end with clove hitches and get

tighter with fraps. All together, they form a lashing.

From

Survival, FM 3-05.70 (FM 21-76), by the Headquarters, Department of the

Army, page G-1 to G-2

2 The

Ashley Book of Knots, by Clifford W. Ashley, page 186.

4

Ibid., page 11, 290 and 305.

5

I don’t know where I first heard this called a “magic grommet”, probably

from another Birchbark Expeditions guide, but the name stuck with me.

6 The

Ashley Book of Knots, by Clifford W. Ashley, page 290 and 599.

Sources

Ashley,

Clifford W.; The Ashley Book of Knots, [Geoffrey Budworth, Kent,

England, 1993], https://www.liendoanaulac.org/space/references/training/Ashley_Book_Knots.pdf, accessed January

25, 2022

Boy

Scouts of America, Knots and How to Tie Them, [2002]

Hasluck, Paul N.; Knotting

and Splicing Ropes and Cordage, [David McKay, Publisher, Philadelphia, PA,

1912], page 44 to 46, https://books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5QadbkrmBx1Gbt4sXfsubEY1Yuq59o5ydbt5SVplV3e8TM4myCFqis5bVfvEV0s-OvwU5BGbaRJcUGrxnzC7Asu1o6uXg62MvTbBQ_6QYOYckKpGoiqHzbVyoAU66wZ0JnfA4CFwlarClPIOfsXJtL241YGwdSq8QP4JVmlXseXQKcnUBebmDlnQU5GLULW42r9WlDMqAZ0679kpgvlvS8sYEFqoXRgHj9hdJuBHcvLagnY8TexhtJKTcbVSsNQEx1uaBeUiT0hMs0kb-cMldIr69Q0lNyu0XQduelZjK7KRd7eNivL0,

accessed January 27, 2022

Headquarters, Department of the Army, Survival, FM

3-05.70 (FM 21-76), [Washington, D.C., May 2002], page G-3, https://irp.fas.org/doddir/army/fm3-05-70.pdf, accessed January 24, 2022

Marco

Products, The Camper’s Knot Tying Card Game, [USA,

1986]