An excerpt from Handbook For Boys, by the Boy

Scouts of America, June 1953, page 157.

This

article can be used by experimental archaeologists, re-enactors

or historical trekkers of the late 18th and early 19th

centuries, or by anyone who is interested in wilderness survival or camping. Updated November 2, 2021 –

Author’s note.

The

lyric, “seeking shelter against the wind”, is from Bob Seger’s song “Against

The Wind”1, and while Mr. Seger was talking metaphorically about

life and it’s struggles and challenges, it is also an excellent piece of

survival advice, as well. So how do you

go about seeking shelter against the wind?

With a windbreak of course! But

is there a science to windbreaks? Why

yes, there is!

Much

of what has been written about the science of windbreaks has come from the

viewpoint of agricultural scientists, writing about providing shelter for

wildlife and livestock, but hey if it works for moose and cows, it will work

for you too!

The

purpose of a windbreak is, obviously, to break the wind, this reduces the

effects of wind chill and at the same time protects you from wind-blown rain,

sleet, and snow. You can either find

windbreaks, like large rocks, fallen trees, or thickets and groves of trees, or

you can build them yourself from the materials at hand in the wilderness. There are two types of windbreaks, solid ones

like rocks, walls and logs, and permeable ones like groves of trees and

thickets, which are also called shelterbelts.

As

the wind blows against a solid, straight windbreak, it

is either forced around or over it. When

air is forced over a windbreak the air pressure increases on the upwind or

windward side and its velocity increases.

On the downwind or leeward side, a slight vacuum is created as the wind crests

the top of the obstacle. This vacuum

causes turbulence, which acts to dissipate the wind’s energy and velocity. The area of wind protection downwind from a

solid windbreak is about fifteen times the height of the windbreak.

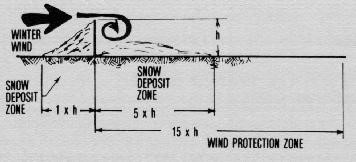

Solid windbreaks, Figure 1, from “Wind And Snow

Control Around The Farm”, by Don D. Jones, William H. Friday, and Sherwood S. DeForest.

From “Engineering Practice Planning Guide: Livestock

Shelter Structure”, page 6.

During

the winter, the wind will drop its snow load in two places. On the upwind side of a solid windbreak, snow

will drift at a 45o degree angle in front of it. On the downwind side, the wind no longer has enough

energy and velocity to carry the snow, which then drops out and creates a snow drift. With a solid windbreak, like a fallen log or

a large rock, the distance of this drifting is about five times the height of

the windbreak and a solid windbreak will also protect you from the wind for about

twenty times the height of the windbreak.

The authors of the “Engineering Practice Planning Guide: Livestock

Shelter Structure”, note that there should be a mostly snow drift free area, in

the lee of the windbreak, out to two times the windbreaks height, with the snow

drifting occurring after that out to five times the height of the windbreak2.

Figure 5.1, from “Functioning of a windbreak”, by the Food

and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

A

grove or stand of trees acts as a permeable windbreak and as the wind blows

through a grove of trees, with a vegetation density of 50 to 60%3,

the wind is both forced over and through the trees. Just as with a solid windbreak, when the wind

is forced over a grove of trees, the air pressure increases on the upwind or

windward side and its velocity increases.

On the downwind or leeward side, a slight vacuum is created as the wind

crests the grove and this vacuum causes turbulence, which acts to slow the

wind. The area of wind protection,

downwind from a grove of trees, is between fifteen to twenty times the height

of the trees. The wind reduction provided

by a 32-foot, 10 meter, tall grove of trees can be as much as 70% within the

first 100 feet, or approximately 30 meters, dropping to 50% out to 200 feet, or

approximately 60 meters, from the lee edge of the grove of trees.

|

Figure 5, from “Wind And Snow Control Around The Farm”,

by Don D. Jones, William H. Friday, and Sherwood S. DeForest.

During

the winter, the wind as it blows over a thicket or a grove of trees will drop

its snow load in two places. On the

upwind side of the trees, the snow will drift into the trees and create drifts on

the windward side of the stand of trees.

On the downwind, or lee side, the wind is slowed and no longer has the

energy and velocity to carry snow and the snow then settles out to create a snow

drift. In the lee of a grove of trees,

the distance of this drifting is about five to ten times the height of the grove

and this type of windbreak will also protect you from the wind for about fifteen

to twenty times the height of the grove.

From “Shelterbelt agriculture uses trees to protect

soil and water resources”, by Henry Kock.

During

the spring, summer or fall, the best type of windbreak is a thicket or grove of

trees, and the best spot for protection from the wind, would be somewhere

within five to ten times the trees height, away from the edge of the grove. You will also find that during the summer

that within this area it will be the cooler than anywhere else. According to the “Wind And Snow Control

Around The Farm”, by Don D. Jones, William H. Friday, and Sherwood S. DeForest,

“a dense tree area has a substantial cooling effect. On a hot summer day,

there is up to a 10-degree difference in temperature between an open field and

a grove of trees. This is more than shade effect. The leaves of one mature tree

can evaporate over 200 gallons of water per day, producing evaporative cooling

equivalent to an 8-10 room air conditioner!”

During

the winter, the best spot to be would be about ten times the trees height away

from the edge of the grove. This spot

will give you the best protection from the wind and it will also put you beyond

the snow drift zone4.

However,

in open country, you won’t be able to find a handy thicket or a conveniently

placed stand of spruce trees, and you will have to build a windbreak to protect

your lean-to or your tent. When you

build a windbreak, its final shape will depend on the materials that you have available

build it with. If you are in a forested

area and are using logs, your walls will, of course, be straight, and your

windbreak will be “V” shaped. If you are

using snow blocks, are digging through the snow to the ground and piling the dug-up

snow to the windward side, or are using piled up rocks, the best shape will be

semicircular. In the Arctic, or during

the winter, Alan Innes-Taylor, who wrote the Arctic Survival Guide, suggested

the following about windbreaks.

An excerpt from Arctic Survival Guide, by Alan

Innes-Taylor, page 59.

Also,

the SAC Land Survival Guide Book, most likely authored by Alan

Innes-Taylor, had this to say about windbreaks, “In open country you can

build a low snow-block wall not more than four feet away from the tent and

semicircular in shape. Strengthen the

windward side by throwing water on it and letting it freeze.”

From R. L. Jairell, and R. A. Schmidt, “Snow

management and Windbreaks”, page 2.

From “Engineering

Practice Planning Guide: Livestock Shelter Structure”, page 4. Note that in Figure 1a, the width of the

shelter is labeled “D” and the Drift-Free area is ¾ of the width at 1-½ times

the width from the corner of the shelter.

The

authors of the “Engineering Practice Planning Guide: Livestock Shelter

Structure”, much like the authors of the SAC Land Survival Guide Book, thought

that the semicircular windbreak was the best shape, as the semicircle protects

27% more area, for the same shelter length, than does the “V”-shape

windbreak. They also wrote that, during the winter, whether you are building a “V”-shape

or a semicircle windbreak, if you wished to avoid snow drifts, you should make

sure that the shelter width (which is marked as “D” in both illustrations)

should be no more than fifteen times the total height your walls. This way the snow drift free area behind your

windbreak, will be no less than ¾ of the shelter’s width.

If

the walls of your windbreak are 3 feet, or almost 1 meter high, then the width

of the mouth of the semicircle or “V”, should not be more than fifteen times

the height, which is equal to 45 feet or almost 14 meters. During periods of drifting snow, this will

give you a drift free area in the lee of the windbreak that is 33 feet, or 10

meters wide

So,

the next time you are seeking shelter from the wind, build or find a windbreak

and set up camp in its lee.

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and look for me

on YouTube at Bandanaman Productions for other related videos, HERE. Don’t forget to follow me on both The

Woodsman’s Journal Online, HERE,

and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube. If you have questions, as always, feel free

to leave a comment on either site. I

announce new articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds, on Instagram at

bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch for me.

That

is all for now, and as always, until next time, Happy Trails!

Notes

1

The song “Against The Wind”, by Bob Seger is from the 1980 album, Against

The Wind.

2

So, for example, if you build a wall or find a fallen log or big boulder that

is three feet, or almost 1 meter, high, the wind will create a drift zone in

the lee of the windbreak, that can equal 15 feet, or almost 5 meters, which is

the height of the windbreak times five.

It should be remembered that the area behind the windbreak out to 6

feet, or almost 2 meters, should be mostly drift free. The windbreak will also block or reduce the

wind for about fifteen times the height of the windbreak, which at 3 feet, or

almost 1 meter, will be 45 feet or just over 14 meters.

3

From “Functioning of a windbreak”, Food and Agriculture Organization of the

United Nations,

4

So, for example if you are downwind of an approximately 30-foot, or almost 10

meter, tall grove of spruce trees; the wind and snow will create a drift zone

that can extend as far as 150 feet to 300 feet, 46 to 91 meters, which is the

height of the grove of trees, times a factor of five to ten. The trees will also block and slow the wind

for between fifteen to twenty times the height of the grove, which at 30 feet,

or almost 10 meters, will extend 450 to 600 feet, 137 to 183 meters, from the

edge of the grove.

Sources

3904th

Composite Wing Strategic Air Command, SAC Land Survival Guide Book, [SAC

OFFUT AFB, July 8, 1952], page 66

Boy Scouts of America, Handbook For Boys,

[Boy Scouts of America, New York, New York, June 1953], page 157

Brandle, James R., and

Finch, Sherman; “How Windbreaks Work”, University of Nebraska Extension, EC

91-1763-B, https://www.fs.usda.gov/nac/assets/documents/morepublications/ec1763.pdf, accessed December 10,

2020

Food and Agriculture

Organization of the United Nations, “Figure 5.1 Functioning of a windbreak”, http://www.fao.org/3/t0122e/t0122e0a.htm,

accessed December 10, 2020

Innes-Taylor,

Alan; Arctic Survival Guide, [Scandinavian Airlines System, Stockholm,

1957], page 54-55 and 63

Jairell,

R. L.; and Schmidt, R. A.; “Snow management and Windbreaks”,

[University of Nebraska, Lincoln, December, 1999], page 2, https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1132&context=rangebeefcowsymp, accessed December 10, 2020

Jones, Don D.; Friday,

William H.; and DeForest, Sherwood S., P.E.; “Wind And

Snow Control Around The Farm”, NCR-191, [Purdue University, Cooperative

Extension Service, West Lafayette, IN; 1983], https://www.extension.purdue.edu/extmedia/ncr/ncr-191.html, accessed December 10, 2020

Kock, Henry; “Shelterbelt

agriculture uses trees to protect soil and water resources”, Ecological Agriculture

Projects, [McGill University (Macdonald Campus), Ste-Anne-de-Bellevue, QC, Canada,

1990], https://eap.mcgill.ca/MagRack/SF/Summer%2090%20M.htm,

accessed December 10, 2020

North Dakota,

“Engineering Practice Planning Guide: Livestock Shelter Structure”, May 2016,

pages 3-7, https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/PA_NRCSConsumption/download?cid=nrcseprd1088613&ext=pdf,

accessed December 11, 2020

“Trees can provide living

windbreaks”, The Houghton Lake Resorter, Houghton Lake, Michigan; January 15,

2015, [© 2018-2020 The Houghton Lake Resorter], https://www.houghtonlakeresorter.com/articles/trees-can-provide-living-windbreaks/,

accessed December 10, 2020