|

A fire-safe pot half full of snow, photograph by Author.

To watch a video on “Melting Snow and Ice” for

drinking water, go HERE

– Author’s Note

You

are out in the woods in the winter wilderness and your canteen is getting a

little low, you are surrounded by snow and ice, you don’t need to worry about

water, right? Right?

Well

yes and no. All that snow and ice is

just as pure as the source it came from, which might not be that pure. You should always disinfect any water you

melt out of snow or ice.

You

must turn all that snow and ice into liquid water to disinfect it. If there is plenty of fuel and you can get a

fire started or have a stove, and you have a pot that can withstand the fire,

boiling your water to disinfect it might be your best option. Don’t forget, during winter treks warm drinks

can help you maintain your core body temperature.

For more information on how long to boil your

water to disinfect it, read “Water Disinfection: When is boiled, boiled

enough…?”, HERE.

But,

before you boil it, first you must melt that snow and ice! Did you know that, since snow is such a good

insulator, if you just put a pot of snow over a fire or on a stove you will either

scorch the pot, giving the resulting water an awful smell and a burnt taste, or

you will melt a hole in the bottom of your thin-walled cook pot!

To

avoid burning the bottom of your pot, you need to “prime” the pot with

some liquid water before you put it on the stove or fire to boil. You should always put a small amount of water

into the pot as “seed” water, it acts as a barrier between the heat

source, the pot, and the snow or ice. The article “How to Melt Snow...” recommends putting

a cup (8 ounces or 237 ml) of water into a two-liter (68 ounce) pot and

bringing it to a boil, before you add snow or ice to the pot. Other sources recommend adding about an inch

(2.5 cm) water to the pot and bringing it to a boil before you start adding

snow or ice.

|

A picture of my fire-safe pot, setting by the fire, photograph by the Author.

If

you don’t have any liquid water to “prime” the pot, something you can do

with a fire, but not with a stove is, you can put your pot full of snow and ice

near the fire1 so that the pot and the ice slowly warm up and then

as the pot slowly fills with water, add more ice or compacted chunks of snow to

your “seed” water, stirring occasionally, until you have enough water to

“prime” your pot so that you can put it over the fire to boil.

But

what if you don’t have a fire-safe pot to melt your snow or ice in? The United States Military Manual, Survival

FM 21-76 has the following suggestions regarding how to melt snow and

ice. You could use your body heat to

melt the snow, by placing the snow or ice in a plastic waterbag between your

layers of clothing. This is a slow

process, and it might chill you and put you at risk for hypothermia, but it

could be used if you don’t have a way to make fire or are on the move. Additionally, they suggested that you could

put the snow or ice in a cloth bag, such as a Millbank water pre-filtration

bag, and then hang the bag near (but not over) the fire, above a container to

catch the resulting melt water. In both

cases, if you don’t have a fire-safe pot that can withstand the heat of a fire

or stove, you will have to use UV, mechanical or chemical means2 to

disinfect your water. For more on this

read, “True or False, You Should Drink Water From The Spring Where Horses

Drink? ©”, HERE.

|

A Ziploc® bag of snow, that you could put inside your coat, photograph by the Author.

|

A cloth bag in front of a fire, used to melt water, hanging on a tripod. Photograph by the Author.

Remember

in a short-term survival situation it is better to drink suspect water, than

not drink any at all. As Peter

Kummerfeldt teaches, “A doctor can fix giardia, but he can’t fix dead”,

or “doctors can cure a lot of things, but they can’t cure dead”, I have

echoed this survival refrain since I first heard it in 2005. When worst comes to worst, and you are facing

dehydration, drinking actually or potentially infected water is better than not

drinking any water at all.

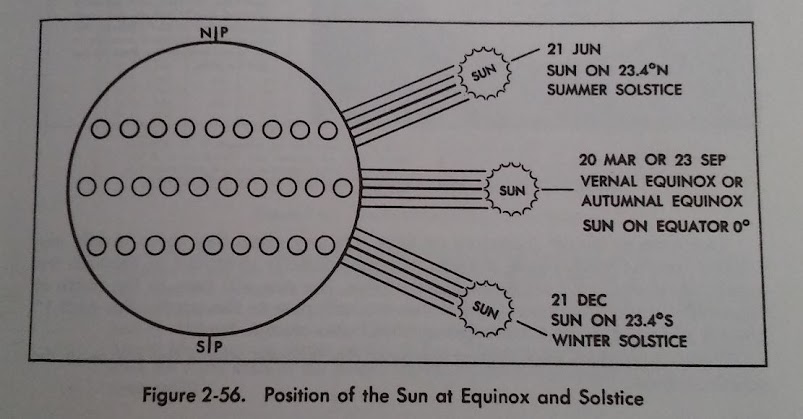

Not

all snow and ice are created equal, and all things being equal, you should use

ice, old granular snow and last of all, fresh, new, fluffy snow in that order

when you are trying to make melt water.

|

An excerpt from How To Survive On Land And Sea, 1956, by Frank C. and John J. Craighead, page 43.

The

reason for this is that the denser the snow or ice you put into your pot the

more water it contains and the more that you will have to drink when it is

fully melted. Ice, which is the densest

of all, is almost all water. Old granular

snow, which is basically small pellets of irregularly shaped ice, is less dense

than ice, but more dense than new snow, it contains more water than new snow,

but less than ice. New-fallen snow is

the least dense and contains the least amount of water.

Additionally,

ice has the least amount of dead air trapped between the individual pieces. Old, granular snow still has a significant

amount of dead air space surrounding the individual crystals, even if you pack

it. New fallen, fluffy snow is, well...fluffy,

and it has the most dead air space trapped around the individual crystals of

snow. The reason why this is important

is that this dead air space is what makes snow such a great insulator and why

it can burn your pot!

|

The author’s firepan, photograph by the Author.

I

built my fire on a firepan, which you can see in the picture above, as I was putting

out my fire. Originally, my firepan was

the base of a broiler tray from an old toaster oven that I re-purposed after it

broke several years ago.

There are two reasons and the first

is that when you use a firepan, it does less damage to the ground below;

particularly, since in this case the firepan is resting on a bed of

gravel. It is always a good idea to

leave as small a footprint as possible, when you wander through the woods.

The second, and more important reason

in this case, is that if the ground is wet or you are in a low spot where the

water table is close to the surface, as the fire grows it warms up the moisture

in the ground below and draws the resulting water vapor upwards, this can make

it difficult to keep the fire going. I

built this fire on a gravel bank, along a frozen creek and the water table was only

inches below it. Plus, there was a lot

of wind-blown snow and ice mixed in with the gravel. None of this would have been good for my fire,

so I put a firepan down and built my fire on top of it.

|

The soggy, cold remains of my fire. Don’t forget to put your fire out when you are done. If you don’t feel any heat coming up from the charcoal and the ashes, then it is out. Photograph by the Author.

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and look for me

on YouTube at Bandanaman Productions for other related videos, HERE.

Don’t forget to follow me on both The

Woodsman’s Journal Online, HERE,

and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube. If you have questions, as always, feel free

to leave a comment on either site. I

announce new articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds, on Instagram at

bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch for me.

That

is all for now, and as always, until next time, Happy Trails!

Notes

1 Survival

FM 21-76 recommends this, especially if you are using improvised pot.

2 For

and excellent article on emergency disinfection of drinking water, read the

EPAs “Ground Water and Drinking Water: Emergency Disinfection of Drinking Water”,

HERE.

Sources

Department

of the Army, Headquarters; Survival FM 21-76,

March 1986, [Washington, DC], pages 5-2 to 5-3 and 15-15 to 15-16

Craighead,

Frank C., and Craighead, John J.; How To Survive On Land And Sea,

[United States Naval Institute, Annapolis, MD, 1956], page 43

Lewicky,

Andy; “How To Melt Snow For Water”, May 17, 2008, http://www.sierradescents.com/2008/05/how-to-melt-snow-for-water.html,

accessed January 23, 2021

Nesbitt,

Paul H., Pond, Alonzo W., Allen, William H.; A Pilot’s Survival Guide,

[Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, New York, 1978], pages 130-131

Schimdt, David; “Winter Camping Skills: Melt

Water”, October 29, 2010, updated February 14, 2017, [© 2021 Pocket Outdoor

Media Inc.], https://www.backpacker.com/skills/winter-camping-skills-melt-water, accessed January 23, 2021

Werner,

Philip; “How to Melt Snow…Without Burning a Hole in Your Cooking Pot”, [©

Copyright 2007-2020, SectionHiker.com and Fells Press LLC], https://sectionhiker.com/how-to-melt-snow-without-burning-a-hole-in-your-cooking-pot/,

accessed July 29, 2020