But first, before

you go...

survive a wildfire is to not be caught in one!

survive a wildfire is to not be caught in one!

So,

first, before you go pay attention to the news, check with the ranger station,

and read the weather forecasts for the area you are going to visit, to find out

if there is a fire, OR if the conditions are ripe for a blaze.

A

good source for weather conditions is the National Weather Service, HERE, and HERE, which issues red flag warnings, when the dry, unstable conditions

exist, that are ideal for a wildfire.

Thunderstorms bring lightning, which is

frequently the spark that touches off a forest fire, and winds, which fan the

flames; so be extra careful if the forecast calls for thunderstorms. And be extra careful during the afternoon

hours, when temperatures are the highest and humidity is the lowest.

If fire weather conditions exist, but there are no active fires, remember to follow all the rules and regulations regarding campfires and open burning, because you don’t want to be “THAT guy”, you know, the one who burnt up thousands of acres because he was careless!

Always

plan escape routes in case a wildfire develops near

where you are. Have at least two escape

routes, so that you can escape no matter what direction the wind is blowing,

towards or away from you.

Use

the concept of “BINGO Fuel” to help you plan your escape routes. “BINGO Fuel” is military slang for the

absolute minimum amount of fuel necessary for an aircraft to return to its

point of departure or an alternate landing strip. But, since you’re not a plane, change “fuel”

to “time”. “BINGO Time” is the absolute

minimum amount of time required for you to turn around and safely reach the

trailhead or another point of safety. It

is like the “point of no return”; that point in time where the daylight remaining

is exactly equal to your minimum “BINGO Time”.

If You Spot a Fire…Remember, it is better to be safe than sorry, so if you see signs of danger, such as smoke or flames, turn around and get out of Dodge! And when you get back to the trail head, contact 911, the county sheriff’s office, or the local rangers to report the fire.

Often

the first indication you will have that there is a fire nearby, is smoke! But it is important to remember that smoke

and ash can travel long distances, so there is no need to panic at the first

sight or scent of smoke. Wildfire smoke

can either be a general haze or a large column, boiling up from the ground!

If

you see are experiencing a general smoky haze, instead of column of smoke, then

you may OR may not be close to the source of the fire.

If

the source of the wildfire is far away, you might still be in danger because,

as everyone knows, breathing in smoke is bad for your health, and wildfire smoke

is full of nasty particles that can damage your lungs if inhaled. A light smoke or haze can leave you with a

runny nose, eye irritation and a sore throat, but a heavier smoke or haze can

cause chest pain, difficult breathing, coughing, and wheezing.

“Quebec Canada Wildfire Smoke Consumes New Jersey and New York City June 7, 2023”, by Anthony Quintano, from Wikimedia, showing “hazardous” air conditions.

So,

if you do encounter smoky or hazy air, you can determine the level of damaging

microparticles by observing the color of the sky or the thickness of the haze. If the sky is a yellowish orange to red hue, the

air is “unhealthy”, and you should leave immediately.

Another

way to determine air quality is by how far you can see. If you can see objects more than ten miles

(16 km) away the air is “good”.

If you can only see objects five miles (8 km) away, the air is “unhealthy”,

and you should consider leaving the area.

But if you can see less than one mile (less than 2 km), then the smoke levels

are “hazardous”, and you should leave the area immediately.

“Smoke column rises at the High Park Wildfire”, by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, June 22, 2012, from Wikimedia.

If you see a column of smoke, instead of a general smoky

haze, then you are close to the source of the fire. You can use the smoke

plume to make an educated guess of how far away, how big, and what direction

the fire is burning in. This will help

you assess what escape route to use and how dangerous the fire is to you. Smoke signals to look for are:

White smoke is an indicator of fire burning finer, fast burning fuels such as grass, and means that the fire is likely a fast moving, short duration fire.

Dark smoke indicates a longer lasting fire that has the potential for “spotting”. A fire that is “spotting” carried embers aloft in the smoke plume, sparking fires ahead of the main blaze.

The bigger the smoke column is, the bigger the fire is. If the column gets bigger, then the fire is growing.

If you suddenly get smoked-out, or see a nearby smoke column, it is time to head for your escape route.

“Rough Ridge Fire Smoke Columns”, National Wildfire Coordinating Group, November 11, 2016, from Wikimedia, adapted by the Author.

The direction the smoke column is bending towards is the direction the fire is moving to. Fires generally move downwind, and the smoke blows away from the fire. Fires blown by the wind can move quickly, burning at 20 mph (32 kph), or more per hour.

Remember, don’t try to outrun the fire! Instead, if the smoke is blowing 180o

away from you, escape by moving upwind, opposite to the bending plume. If the smoke column is bending towards you or

at 90o’s from your path, escape by moving perpendicular to the direction

of the wind and smoke plume.

A rising smoke column, going straight up, is a good sign, and means that there is little to no wind pushing the flames, and it will move slowly.

By checking on the conditions before you go, by having a couple of escape

plans ready to go, by observing the color and visibility of the sky and by

analyzing the smoke plume, if you come upon one, you can avoid the risks tied to

wildfires.

Don’t forget to come back next week and read the exciting conclusion

of “Surviving a Wildfire! If You Get

Caught in a Fire, Part Two ©”, where we will talk about how to survive a

wildfire, when the flames have gotten way too close!

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and look for me

on YouTube at BandanaMan Productions for other related videos, HERE. Don’t forget to follow me on both The

Woodsman’s Journal Online, HERE,

and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube. If you have questions, as always, feel free

to leave a comment on either site. I

announce new articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds, on Instagram at

bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch for me.

That

is all for now, and as always, until next time, Happy Trails!

Sources

Countryman, Clive M.; Heat-Its

Role in Wildland Fire- Part 1, [U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest, 1975], https://books.google.com/books?id=9-4TAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Fuels+for+Radiation+and+Wildland+Fire&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiH_eO1vsH_AhVSFVkFHXwmAuQQ6AF6BAgDEAI#v=onepage&q=Fuels%20for%20Radiation%20and%20Wildland%20Fire&f=false,

accessed June 13, 2023

Countryman, Clive M.; Radiation

and Wildland Fire, [U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific

Northwest, 1976], https://books.google.com/books?id=H2h0yRloLdwC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Fuels+for+Radiation+and+Wildland+Fire&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiH_eO1vsH_AhVSFVkFHXwmAuQQ6AF6BAgHEAI#v=onepage&q=Fuels%20for%20Radiation%20and%20Wildland%20Fire&f=false,

accessed June 13, 2023

Go Explore Croatia; “How

To Survive a Forest Fire”, [© 2016 Go Explore Croatia], https://goexplorecroatia.com/croatia-travel-blog-news/how-to-survive-a-forest-fire/,

accessed June 10, 2023

Green, Lisle R.; Burning

by Prescription in Chaparral, [U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest

Service, Pacific Northwest, 1981], https://books.google.com/books?id=j2OYEfplwCEC&pg=PA31&dq=%22smoke+columns%22+wind+direction&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjmgJne0MH_AhUvFlkFHcG_AUc4FBDoAXoECAMQAg#v=onepage&q=%22smoke%20columns%22%20wind%20direction&f=false, accessed June 13, 2023

Kia; “How to Escape a Wildfire:

A Hikers’ Guide”, April 14, 2021, [© 2023 ATLAS & BOOTS], https://www.atlasandboots.com/travel-blog/how-to-escape-a-wildfire-a-hikers-guide/,

accessed June 10, 2023

Olivier, Jonathan; “How

to Escape a Wildfire When You’re Hiking”, June 26, 2018, [© 2023 Outside

Interactive, Inc], https://www.outsideonline.com/outdoor-adventure/hiking-and-backpacking/daily-rally-podcast-lyla-harrod/,

accessed June 10, 2023

Piven, Josh; “Survival

strategies to help you escape a forest fire”, Scouting magazine, May-June 2016,

[© 2023, Boy Scouts of America], https://scoutingmagazine.org/2016/04/survival-strategies-help-escape-forest-fire/,

accessed June 10, 2023

REI; “Wildfire Safety

Tips for Outdoor Recreation”, [© 2023 Recreational Equipment, Inc], https://www.rei.com/learn/expert-advice/wildfire-safety-tips-for-outdoor-recreation.html,

accessed June 10, 2023

Schroeder, Mark J., and

Buck, Charles C.; Fire Weather: Agricultural Handbook 360, [U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Broomall, PA, May 1970], https://books.google.com/books?id=j4f_lBHsSKEC&pg=PA88-IA2&dq=%22smoke+columns%22+wind+direction&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjI6r_dzsH_AhX4EWIAHYqwCwgQ6AF6BAgHEAI#v=onepage&q=%22smoke%20columns%22%20wind%20direction&f=false,

accessed June 13, 2023

Soares, John; “Surviving

a Wildfire While Hiking: What to Do”, July 28, 2018, [© 2023 by John Soares], https://northerncaliforniahikingtrails.com/blog/2018/07/28/surviving-wildfire-hiking-what-do/,

accessed June 10, 2023

The Trek; “How to Stay

Safe While Hiking During Wildfire Season”, [© 2023 Copyright The Trek], https://thetrek.co/how-to-stay-safe-while-hiking-during-wildfire-season/,

accessed June 10, 2023

Wikimedia; “A picture of

the empire state building”, by @Aelthemplaer on Twitter, June 7 2023, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Empire_State_Building_on_June_7,_2023.jpg,

accessed June 10, 2023

Wikimedia; “Quebec Canada

Wildfire Smoke Consumes New Jersey and New York City June 7 2023”, by Anthony

Quintano, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Smoke_from_2023_Quebec_wildfires_in_New_York_City#/media/File:Quebec_Canada_Wildfire_Smoke_Consumes_New_Jersey_and_New_York_City_June_7_2023.jpg,

accessed June 21, 2023

Wikimedia; “Rough Ridge

Fire Smoke Columns”, National Wildfire Coordinating Group, November 11, 2016, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rough_Ridge_Fire_Smoke_Columns_2016_11_11-11.45.51.039-CST.jpg,

accessed June 21, 2023

Wikimedia; “Smoke column rises at the High Park Wildfire”, by the U.S.

Department of Agriculture, June 22, 2012, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Smoke_column_-_High_Park_Wildfire.jpg,

accessed June 21, 2023

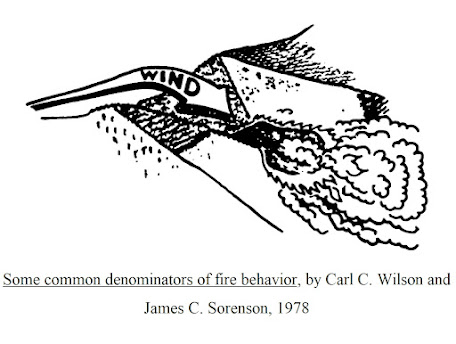

Wilson, Carl C., and

Sorenson, James C.; Some common denominators of fire behavior, [U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Broomall,

PA, December 1978], https://books.google.com/books?id=w_tq7y2v8I4C&printsec=frontcover&dq=smoke+wind+direction+wildfire&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi78oTswcH_AhUxMVkFHSE_Dd04ChDoAXoECAkQAg#v=onepage&q&f=false, accessed June 13, 2023

_(NYPL_b12647398-74024).tiff.jpg)