From Storrs & Harrison Co; Henry G. Gilbert Nursery and Seed Trade Catalog Collection, Spring 1899.

Have

you ever heard of turnip bread, or as they spelled it 1693, “turnep-bread”? It was a type of bread that poor people when flour

was scarce. I had never heard of it

before and so, I thought, in honor of the American Thanksgiving, that I would

give it a try.

Now

I know what you are thinking, usually I write about survival and yet here I am

writing about bread recipes, did I morph suddenly into a food blogger?! No, and while it would seem that making bread

and bread recipes has nothing to do with survival, bread and grains are the “staff

of life”1 and sometimes your survival might depend on how far

you can stretch them.

An excerpt from Bread the Staff of Life, by the Religious Tract Society, 1830, modified by the Author.

Unfortunately,

over the last 10,000 years that humans have been relying on grain products for

food, there has been famine after famine, war after war, and poor harvest after

poor harvest. Often grain has been scarce

and hard to come by, particularly if you were poor. So, poor people learned to stretch scarce and

expensive grains by making bread with a mixture of grain and saw-dust, the

inner bark (cambium) of trees, such as scots pine, elm, ash, aspen, rowan or birch,

peas, beans, pumpkins, potatoes or even turnips!

Turnips and wheat, making bread possible even in times of scarcity! Excerpts from Mrs. Beeton’s Cookery Book and Household Guide, pages 187 and 220.

I

thought that I would try turnip bread, so I searched out three early recipes,

or “receipts” as they would have been called in 18th century,

for making wheat go farther by mixing it with turnips.

From the The Essex Naturalist, page 182 to 183.

The

earliest I found, was from Samuel Dale, and was written on December 6th,

1693, and later reprinted in The Essex Naturalist, 1907-1908 edition. This recipe used natural fermentation to leaven

the bread.

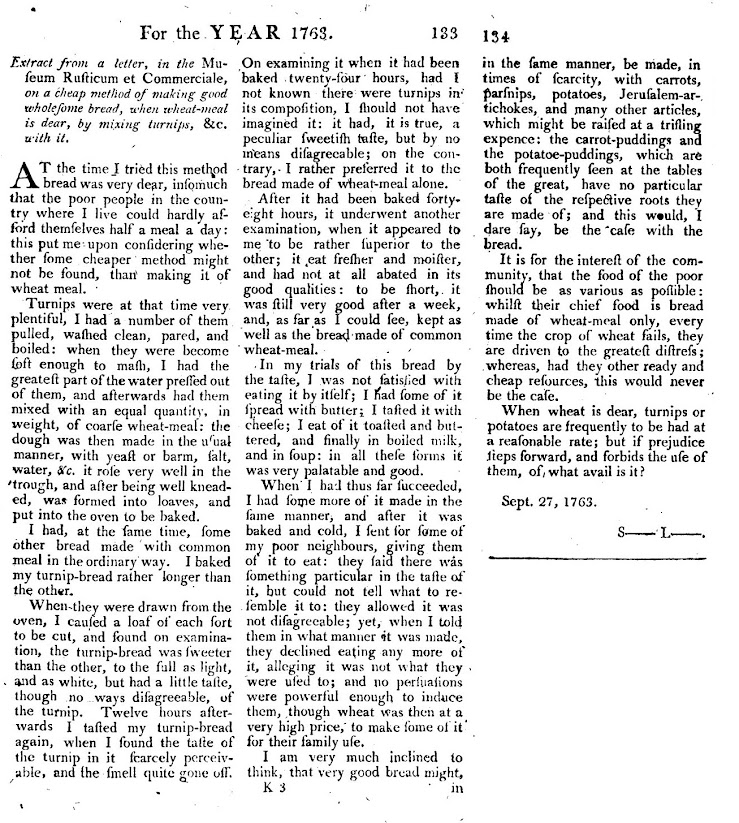

An excerpt from The Annual Register of World Events: A Review of the Year 1763, pages 133 to 134.

The

next was from September 27th, 1763, and the author stated that “the dough

was then made in the usual manner, with yeast or barm”2 as a

leavening agent. Interestingly, this

author also experimented on the taste and keeping power of the resulting loaves

of bread, by taste testing them over a period of 48 hours.

An excerpt from The Gardeners’ Chronicle and Agricultural Gazette, April 24, 1847, page 269.

And

the last recipe I found, was published on April 27th, 1847, in the Gardeners’

Chronicle. This recipe, instead of

using yeast to leaven the dough, used sour milk3 and baking soda to

make the dough rise.

An excerpt from; Bread the Staff of Life, by the Religious Tract Society, 1830, page 12.

The

three recipes shown above, all called for equal weights of whole wheat flour

and mashed turnips. They also, all

assume that the reader has a great deal of knowledge of the science making

bread, something that unfortunately most modern people no longer have. Also, they use terms like barm and sour milk,

which might be unfamiliar to modern bread makers. So, here is a version of the three recipes

above, morphed into something that we would be familiar with today, using an Irish

Soda Bread recipe found, HERE,

and Mrs. Beeton’s Soda Bread recipe, below, as models.

An excerpt from Mrs. Beeton’s Cookery Book and Household Guide, page 221.

What

you will need:

· 6

U.S. cups, = 1-¾ pound, or about 794 grams of whole wheat unbleached flour4

· 1-½

tsp (teaspoonfuls), or 9 grams of baking soda5

· 1-½

tsp (teaspoonfuls), or 9 grams of salt

· 3

U.S. cups , = 708 ml of buttermilk or sour milk7

Turnips on a pewter plate, photograph by the Author.

Drained and mashed, boiled turnips. Note the liquid remaining in the bowl, even though they already drained once, photograph by the Author.

Drain the mashed turnips well, in

fact when I make this bread again, I will put the mashed turnips into a cloth

bag and squeeze the liquid out.

Incidentally, save some of the turnip water, in case your mix is too dry,

and some water is needed for the dough.

Sour milk, an excerpt from The Dairy, May 20, 1916, page 112.

In

the days before widespread refrigeration, milk would often go sour, so a frugal

cook found ways to use milk that was slightly off. Bacteria acting on the milk sugars produce

lactic acid, souring it, and when the acid in the sour milk is mixed with baking

soda, which is a base, carbon dioxide bubbles are produced.

Today,

most people don’t have a ready supply of sour milk lying about the house, so

instead you can substitute an equal measure of buttermilk, or you can sour some

milk by using lemon juice or vinegar.

Making sour milk, photograph by the Author.

Now,

if you don’t have any buttermilk, sour some milk by add one tablespoon (½ of a

fluid ounce), or 15 ml, of either vinegar or lemon juice to a one cup measuring

cup and then fill it to the 8 ounce, or 236 ml line with milk. Stir and let it stand for 5 minutes before

using.

An excerpt from Mrs. Beeton’s Cookery Book and Household Guide, page 221.

While mixing the ingredients preheat the oven to 425°F, or 218oC8.

Mix

the dry ingredients, the flour, the salt, and the baking soda, together with a

whisk or a fork in a large mixing bowl.

Add

the buttermilk, or sour milk, and mashed turnips,

by making a hole or a well in the center of the dry ingredients and pouring them

slowly in, while you stir with a wooden spoon until the dough is too stiff to mix. If there are dry ingredients remaining after

everything is mixed, add a spoon full of turnip water, one

spoon at a time, until the dough is stiff, and all dry ingredients have

been moistened. If the dough is more

like a batter than a dough, add a ½ cup flour, one ½ cup at a time, until the

dough is soft and sticky.

Soft and sticky dough, turned out on a floured bowl to be kneaded, photograph by the Author.

Flour

your hands, before gently gathering the dough into a rough ball shape and transferring

it on to a lightly floured surface. Add

more flour a little at a time and knead the dough just until all the flour is moistened,

and the dough just barely sticks together. Remember, don’t over work the dough, or your bread

will end up tough.

Ready to go into the oven, photograph by the Author.

Put

the loaf into a large, lightly greased cast-iron skillet or onto a baking sheet. Remember, if you are using a baking sheet

without sides, that the dough flattens out. Next score the loaf by using a serrated or

very sharp knife to cut an "X" shape, about an inch and a half deep,

into the top of the loaf. The “X” will

help the heat of the oven, cook the center of the loaf.

An excerpt from Mrs. Beeton’s Cookery Book and Household Guide, page 224.

Put

the bread dough into a pre-heated oven and bake at 425°F, or 218oC,

for an hour or until golden brown and a knife, when stuck into the center of

the loaf, comes out clean and free of dough.

This should take about 35 to 45 minutes for a small loaf. Remember if you make one large loaf, it will

take longer than if you make three or four smaller loaves.

Also,

if you are baking the bread in a cast iron pan, it may take longer than 35 to

45 minutes, because it takes longer for the cast iron to heat up. Also remember, if you use a cast iron skillet

to cook the bread, USE a potholder when you take the pan out, it will be extremely

hot, and you will burn yourself!

If

the top of the bread is getting too dark and your knife or skewer still is not

coming out clean, cover the bread with some aluminum foil. If you wish to be historically accurate, use

paper just as they would have in the late 18th and early 19th

centuries.

When

the bread is done, remove it from the oven, and let the bread sit in the pan or

on the sheet for 5 to 10 minutes. Then

take it from the pan or sheet and move it to a rack to cool briefly. If you place it upside down to cool, it will

help the steam to escape from the loaf of bread.

The bread is done! Next time, I will make 4 smaller loaves, instead of one big one, because it will cook faster. Photograph by the Author.

I

hope you had a safe and Happy Thanksgiving and that there were many glad

tidings to celebrate!

Don’t forget to come back next week and read “Making a Blanket Roll,

Late 19th Century Style ©”, where we will talk about how to carry

your bedroll and necessaries, just like they did right before the 20th

century.

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and look for me

on YouTube at BandanaMan Productions for other related videos, HERE. Don’t forget to follow me on both The

Woodsman’s Journal Online, HERE,

and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube. If you have questions, as always, feel free

to leave a comment on either site. I

announce new articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds, on Instagram at

bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch for me.

That

is all for now, and as always, until next time, Happy Trails!

Notes

1 Grains, such as wheat, barley, and oats, and by extension

bread and any food made from these grains, has been essential for life for the

last 10,000 years. Grains and bread have

been the “staff of life”, since the times of the Biblical prophet

Isaiah, who lived during the 8th-century BCE, and who is quoted in Isaiah 3:1,

as saying “the stay and the staff, the whole stay of bread”. However, it wasn’t until the eighteenth

century that bread, by itself, was called the “staff of life”. The phrase “staff of life” referring

to bread, first appeared in a A Tale of a Tub, published in 1704, by Jonathan

Swift, where he wrote “Bread, dear brothers, is the staff of life”1.

From the “the staff of life”, The Dictionary

of Clichés by Christine Ammer.

2

The modern usage of the word “barm” is as a euphemism for sourdough. However, historically barm was cultured from

the live yeast cells, scooped from the surface of the top of fermenting beer,

and the best barms are the yeasts from traditional ales, not lager. According to author Alex Ketchum, “Barm is a

polyculture of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae families, and ‘rouge’ yeasts were

excluded by careful management. Modern ‘baker's

yeast’ was isolated from barm in the 19th century, and monocultured”.

From Baking with Barm: Part II of the Surprisingly Long

History of Brewing Mugs' Shot IPA”, by Alex Ketchum

3

Sour milk is naturally fermented milk, that has become sour due to lactic acid,

and this is what happens when milk is stored at room temperature for 24 to 48

hours. Sour milk was readily available

to bakers of the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, before

the widespread use of refrigeration. Milk

that hasn’t soured is called “sweet milk”, because the sucrose hasn’t been

changed to lactic acid yet. Sour milk,

or buttermilk, when used with baking soda will leaven bread dough.

4

One U.S. cup of whole wheat flour weighs about 4.6 ounces, or 130 grams

From

the The Gourmandise School, HERE.

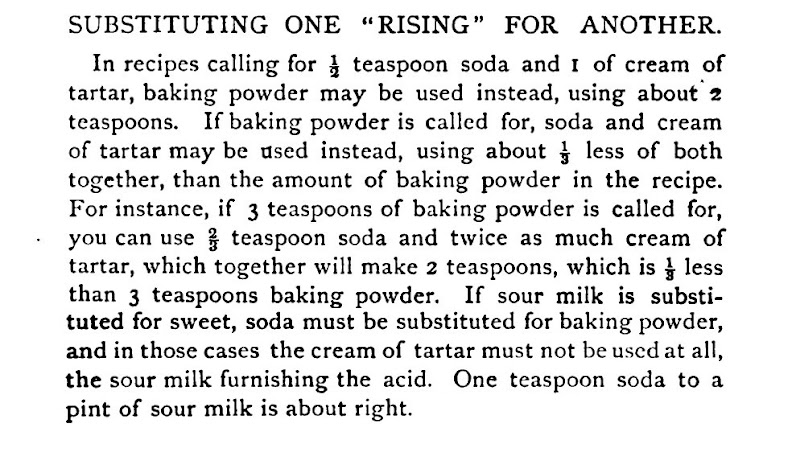

5

Wood ash, pot ash and later baking soda were the first non-yeast leavening

agents, baking powder came later. Mrs.

Beeton’s recipe called for 1 dessertspoonful of baking powder, which is equal

to two teaspoonfuls (tsp) or about 10 grams in modern terms, and according to

Mrs. Owens’ Cook Book, one third less of baking soda should be used if

substituting it for baking powder, so 1 dessertspoonful of baking powder is

equal to 1 teaspoonful and another ¼ heaping teaspoonful of baking soda (One

third of 1 tsp is equivalent to a heaping ¼ tsp).

An excerpt from Mrs. Owens’ Cook Book and Useful Household Hints, page 152 to 153.

6

One US cup of turnips, cooked, boiled with salt, mashed, and drained, weighs about

8.1 ounces or 243 grams

From

“Weight of Turnips, cooked, boiled, drained, with salt (mashed)”, HERE.

7 A

ratio of ½ a tsp of baking soda per cup of sour milk or buttermilk should be

used

From

The Dairy, May 20, 1916, page 112

8

Old

recipes are notoriously loose on temperatures, mostly because stoves and ovens

didn’t have thermometers, so cooks talked of how long flour will take to brown or

used such terms as “a very hot oven”?!

|

An excerpt from Mrs. Owens’ Cook Book and Useful

Household Hints, page 151. |

Bread

and pastries (according to Instruction in Cookery) should be baked at

temperatures between 340 and 410oF, or 171 to 210oC, with

smaller loaves being cooked at a higher temperature and larger loaves being

cooled at a lower temperature, In the

past cooks relied on the browning of flour to determine the heat of their

ovens. According to Camping &

Wilderness Survival if you sprinkle a teaspoon of flour on a pan or heated

surface, the color of the flour after five minutes will indicate the

temperature.

Temperature Flour Turns

250-325oF 121-163oC Delicate brown

325-400oF 163-204oC Golden brown

400-450oF 204-232oC Deep brown

450-500oF 232-260oC Deep dark brown

From

Camping & Wilderness Survival, by Paul Tawrell, page 445; Mrs.

Owens’ Cook Book and Useful Household Hints, by Frances E. Owens; and from Instruction

in Cookery, by A. P. Thomas.

Sources

Ammer,

Christine; “the staff of life”, The Dictionary of Clichés [© 2013, Christine

Ammer], https://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/the+staff+of+life,

accessed November 22, 2022

Beeton, Mrs.; Mrs. Beeton’s Cookery Book and Household Guide, [Ward,

Lock & Co., Limited, London 1898], page 187, https://books.google.com/books?id=vsBQAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA187&dq=%22turnip+bread%22+recipe&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwihv7e51bH7AhX5MlkFHderCrEQ6AF6BAgMEAI#v=onepage&q=%22turnip%20bread%22%20recipe&f=false,

accessed November 15, 2022

Burke, Edmund, Editor; The

Annual Register of World Events: A Review of the Year 1763, [Published by

J. Podsley, London, 1796], pages 133 to 134, https://books.google.com/books?id=ie8HAAAAIAAJ&pg=RA1-PA133&dq=%22turnip+bread%22&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi78eurw6z7AhVUFlkFHWOND6wQ6AF6BAgHEAI#v=onepage&q=%22turnip%20bread%22&f=false,

accessed November 13, 2022

Cole, William; The

Essex Naturalist: Journal for the Essex Field Club for1907-1908, [Essex

Museum of Natural History, Stratford, Essex, UK, 1910] page 182-183, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Essex_Naturalist/1Iw1AQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=charcoal+burners+hut+walton&pg=RA1-PR10&printsec=frontcover,

accessed November 11, 2022

FoodHero.org; “Turnip

Monthly”, [Oregon State University, 2017], https://www.foodhero.org/sites/foodhero-prod/files/monthly-magazines/Turnip%20Monthly.pdf,

accessed November 20, 2022

Ketchum, Alex; “Baking with Barm: Part II of

the Surprisingly Long History of Brewing Mugs' Shot IPA”, January 8, 2015, http://www.historicalcookingproject.com/2015/01/baking-with-barm-part-ii-of.html,

accessed November 21, 2022

The

Creamery Journal; The Dairy, May 20, 1916, Volume XXVIII-329, page 112, https://books.google.com/books?id=7yA3_rOaxYEC&pg=PA112&dq=how+to+make+sour+milk&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi1tKKPt737AhWAFFkFHSJDAagQ6AF6BAgBEAI#v=onepage&q=how%20to%20make%20sour%20milk&f=false, accessed November 20, 2022

The Gardeners’ Chronicle

and Agricultural Gazette, April 24, 1847, No. 17 – 1847, [Published for The

Proprietors, London, 1847, page 269, https://books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5QacrAQUNnyoKoATk65_oUzgJ-5Qw-_1w8MjG3Wrof5PJcBbFB_ZRaGwFqhTy1wvAvHi8fRlmy_GFpfRklR_NurajXiVIANSWmmUDWTJBMjD9eDxck5uxhEKTuQ2LQfXS3d9_okFzv-IvAUeyjppGK-JSKyUjbv3fY8YbW_KQh4ANcEsKAnuNCVmAbD4TZTLSgQIUSyCIAmzXOwqehCOpq36pCZHutxRLgsw5lu2Sy_2m4TUAwVq0h128hVChYRYZmLS6Y92G,

accessed November 15, 2022

Ketchum, Alex; “Baking with Barm: Part II of

the Surprisingly Long History of Brewing Mugs' Shot IPA”, January 8, 2015, http://www.historicalcookingproject.com/2015/01/baking-with-barm-part-ii-of.html, accessed November21, 2022

Owens, Frances E.; Mrs. Owens’ Cook Book and Useful Household Hints, [Owens

Publishing Company, Chicago, 1884], page 153 to 154, https://books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5QacnlrFB1QFi1l1oPHepJzsJgAFKb7SMU6GaXdiyatLh4S3ERkGMXw3LDEX8lsEiON0VThfQM25xYVneiTxiuezYXKPgB38xFlid53VJT-6KnLoJcYWffj7zlzi1YOF7F2ZYFvUcW2xhV2U3OyyvTMuZnMLmVsSx4nWh3zCUNV2JJcia9WWrwLE3QNkdDbrAc-PYpj78SXmKzqmaLu_Frq6DppH-Bu7NNI-kZU5hOsZ01z8Yio8pBZFGgYcf3uGrk5fNfClbZCd9slI9EvWBUPaUrCpfEuYcfEmvg2uw767iGo7nMeI,

accessed November 20, 2022

Religious

Tract Society; Bread the Staff of Life, [Published

by J. Davis and J. Nisbet, London, 1830], page 12, https://books.google.com/books?id=wgpGD7hfCGUC&printsec=frontcover&dq=bread+%22staff+of+life%22&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiq3KG_qcL7AhX3jIkEHW3qCKsQ6AF6BAgFEAI#v=onepage&q=bread%20%22staff%20of%20life%22&f=false,

accessed November 22, 2022

Thomas, A. P.; Instruction

in Cookery, [Methuen & Co., London, 1908], page 11, https://books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5QadDrjvYXiLbpF9lrNudX4ej5_Uf37Uz4sidDWxElnhC-Zfhpswd-C5cg1sN1adAP1-LDaMmTC8loWjPIZFKfbskdoLyX5BO1Odc21wy2yQuBDLjZ_EXF8gUi93I3agALne9PQVOUrqHtCa24WWsXNm4S5B_pKP0UMqKmWQg0RTfsRsShk2jNlXIuGkPBztPf8hbwLew2lvioslD24e9zz3oucCXYO3WT3eg0rseztNEumoVHxB5bVtTB3WKWCj9S500hoMx-pfOZketDxwi-WfWrgILsQ,

accessed November 26, 2022

Wiley, Dr.; “Dr Wiley’s

Question-Box”, Good Housekeeping, June 1916, [Good Housekeeping

Magazine, June 1916, New York], page 784, https://books.google.com/books?id=_C8GzbMN-jEC&pg=RA5-PA783-IA1&dq=%22sour+milk%22+%22soda+bread%22&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjxhsDulMz7AhXNFlkFHcbWAuw4FBDoAXoECAQQAg#v=onepage&q=%22sour%20milk%22%20%22soda%20bread%22&f=false,

accessed November 26, 2022

_(20562686581)%20ed%20trimmed.jpg)

_(20562686581)%20ed%20trimmed.jpg)