|

| “Individual Aid and Survival Kit” carriers, concept one, from “AD 401819, Department of Army Approved Small Development Requirement for Individual Aid and Survival Kit for Special Warfare”, which can be found HERE. |

So,

did you ever wonder what survival supplies were issued to the Special Forces

during the Vietnam War? Did you ever

wonder what these soldiers thought of the survival supplies that Uncle Sam

issued?

No? Well maybe you are wondering about it now

that I have mentioned it. And anyways,

more to the point what is in your survival kit today and how does it compare to

what these soldiers carried during the 1960s and 70s.

|

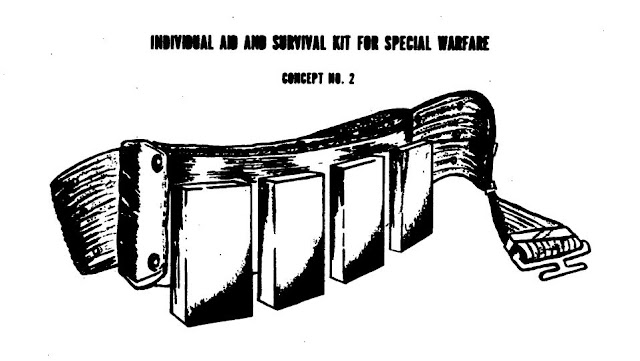

| “Individual Aid and Survival Kit” carriers, concept two, from “AD 401819, Department of Army Approved Small Development Requirement for Individual Aid and Survival Kit for Special Warfare”. |

Discussion

and development of a “Individual Aid and Survival Kit” for the Special

Forces and other special warfare soldiers began in 1963. The goal of the kit, in the words of the

designers, was “...to provide minimum essential self-aid and survival

articles for a period of ten days, when supplemented with foraged foods”1.

The

designers felt that the kits “...must be small enough to encourage its

constant wear in order to insure its ready availability in time of emergency”

and “...if possible, volume should not exceed 44 cubic inches (721 cubic

centimeters), and additionally, that they should “...have a medical, utility

and operational”2 function.

To do this the kit would have to be built in two sections, or as the

report calls them, “components”. Each of

these two sections were to be put inside a durable water-proof liner bag,

inside a rugged container. The

“Individual Aid Kit”, or operational portion, was to be issued empty, so that it

could be customized by the user to suit local needs and it was intended to provide

two to five days of support and supplies.

The “Survival Kit”, which included medical supplies, survival tools and

a survival booklet, was sealed to “...discourage premature consumption”3

of its contents and to protect it from weather, before being put inside its water-proof

liner and outer container. The entire “Individual

Aid and Survival Kit”, less any items intended for the “operational” portion of

the kit, was to have weighed no more 24 ounces (680 grams).

The

designers also felt that it was important that the two components of the “Individual Aid and Survival Kit” should be able to be

attached to a belt and worn either at the small of the back, across the chest,

or slung from the shoulder.

Alternatively, they should be able to be detached from the belt, separated,

and attached to pack straps or carried elsewhere on the soldier’s body.

Additionally,

the durable water-proof liner bag was intended to be

used as an emergency water carrier.

The

designers also had the following advice to potential manufactures of the “Individual

Aid and Survival Kit”:

“Matches,

irrespective of type, are not desired. A

small, simple, all-weather fire-making device is desired.”

“Space

provisions must be made in the kit for a durable map, approximately 28” x 21”, (folded

size approximately 2½” x 4” x ¼”)”, in metric measurements this would be about

71 cm x 53 cm and when folded it would be approximately 6 cm x 10 cm x .6 cm.

“A

durable survival pamphlet must be included in the kit.”

“The

medical component should include as a minimum:”

“A chemical means of water

purification in sufficient quantity to provide the user potable drinking water

for a ten day period, assuming an average consumption of two quarts (1.9

liters) per day.”

“Analgesics for relief of minor

aches, pains, and fevers.”

“A capability for the treatment of

minor cuts, abrasions, burns, and blisters.”

“Remedies and/or suppressants for

major prevalent diseases endemic to areas outside of CONUS (Continental

United States—Author’s Note).”

“The

utility component should include as a minimum:

“A capability for the user to kill,

snare, or other-wise catch small game and fish.”

“A tool for cutting vines, palm

fronds, or foliage for construction of a shelter.”

“A small compass for land navigation.”

“A simple sewing kit.”

“Signalling devices to attract

attention of rescue aircraft or parties.

Consideration should be given to a simple reflecting surface for

daylight signalling.”

“A small, sharp, cutting blade.”

“An insect repellent for user needs

for a ten day period.”

So,

what did the Special Forces soldiers think of the military “Individual Aid and

Survival Kit”, after it was delivered to them for field testing? Major Charlie W. Brewington, Commander of Detachment

B-22, 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne), 1st Special Forces,

wrote an evaluation of this kit, in Annex H of “374659, Employment Of A Special

Forces Group (U)”, found HERE. During the evaluation of this kit, the 5th

SFG also evaluated the survival kit issued to Army Aviation personnel in

Vietnam and the prototype kit that they created and recommended was made up of

the best parts of the two kits. It was

concluded that “...personnel in a survival situation will have a canteen and

a cup and a sheath knife” and therefore these items do not need to be included

in a survival kit. Additionally, since soldiers

in such a situation will be expected to live off the land, the inclusion of

rations in the survival kit was not necessary.

The

survival kit that the 5th SFG evaluated, as shown in Concept Number

4, as part of its medical component, was to include 25 Tetracycline or

Oxytetracycline tablets, both of which are antibiotics used to treat malaria,

anthrax and various infections caused by microorganisms, such as gram positive

and negative bacteria, chlamydiae, mycoplasmata, protozoans and

rickettsiae. The 25 Spensin tablets were

anti-diarrheal medicine, like modern loperamide tablets. The kit was designed to include APC (aspirin,

phenacetin, and caffeine) plus codeine phosphate as a painkiller, the kit that the

5th SFG evaluated contained 10 tablets of 65 mg Darvon to treat mild

to moderate pain. The kit also included 10

Dexedrine tablets (dextroamphetamine sulfate) which during special warfare military

operations have practical applications, but during civilian emergencies in the

wilderness are not necessary.

The

conclusions of the 5th Special Forces Group was that the kit, with

its two packets, was too bulky to be easily carried day in and day out and that

it needed to be tailored more to the hot-wet environment in which the soldiers

were operating. They felt that the outer

nylon carrier and inner durable water-proof liner bag worked, however they felt

that all of the pills should be packaged in plastic vials and the salves and

ointments should be packaged in plastic squeeze bottles to eliminate the

possibility of breakage. Apparently, just

like with many of the medicines packaged in the 1960s and 70s, the bottles were

glass and the tubes were aluminum foil.

The

5th Special Forces Group recommended the addition of the following

items to the survival kit:

One 4-inch (10 cm) hacksaw blade to replace

the chain saw that the designers suggested, as it was not of sufficient “...strength

to withstand prolonged use.”5

One bottle of Benzalkonium Chloride

tincture as a topical, anti-microbial wound wash (for information on Benzalkonium

Chloride, read “Alcohol Prep Pads...BZK Towelettes…Hand Wipes…Wound

Wipes...What?! ©”, HERE),

in addition to the 1½ ounce bottle of Betadine solution.

One vial of eight Chloroquine Phosphate

tablets to prevent and treat malaria.

One vial of twelve, 10-grain (648 milligrams)

salt tablets which can be used to replace salt lost due to sweating.6

One 1½ ounce plastic squeeze bottle of a

fungicidal ointment.

Additionally, they increased the number

of bouillon cubes from three to four.

The

5th Special Forces Group also recommended that the bug repellent

include in the kit (which was probably a DEET product) be replaced with a less

pungent one, as the smell could lead to eventual capture. They did suggest the inclusion of a mosquito

head net. And since they didn’t mention

the hemostat, it is possible that that item was eliminated, but maybe not.

So, what is in your personal individual aid

and survival kit? How does it compare to

the ones that the 5th SFG evaluated?

Personally,

my “survival kit”, which I carry whenever I am in the wilderness, has always been

in two parts, and has been since long before I read the “AD 401819, Department

of Army Approved Small Development Requirement for Individual Aid and Survival

Kit for Special Warfare”. My “operational

kit” which contains my headlamp, a BIC ® Lighter

wrapped in duct tape, bug repellent, toilet paper and sun protection lip balm, is

kept in two quart-sized Ziploc® style freezer bags, one inside the other. My operational kit also includes my personal

day-to-day first aid kit, which contains band-aids, ibuprofen, acetaminophen, Benadryl®,

and triple antibiotic ointment pouches, among other things. All this weighs only 8 ounces (227

grams). My survival kit, which is only

opened in emergencies, contains the standard survival supplies, three ways to

make a fire and tinder, a fishing and sewing kit, snare wire, aluminum foil, a

backup flashlight, one large Reynolds® Kitchen Oven Bag, razor blades, and etc. My survival kit also only weighs 8 ounces

(227 grams), so that if you add the operational kit and my compass, which

weighs in at 2 ounces (57 grams), my entire individual aid and survival kit

weighs a total of 18 ounces (510 grams) and is a little less than the maximum

recommended weight of 24 ounces (680 grams).

I

do not carry a hemostat or as many medicines in my survival kit as was in the

kit that the 5th SFG reviewed, however soldiers in the middle of a

war might have been severely wounded before becoming separated from their

units. Also, I do not carry Dexedrine

since I do not have to worry about falling asleep and being surprised by the enemy

if I become lost.

Hopefully, this has given you some ideas on

how to build, and stock a new Individual Aid and Survival Kit or how to rebuild

your current kit.

I hope that you enjoy

learning from this resource! To help me

to continue to provide valuable free content, please consider showing your

appreciation by leaving a donation HERE.

Thank you and Happy Trails!

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and look for me

on YouTube at Bandanaman Productions for other related videos, HERE.

Don’t forget to follow me on both The

Woodsman’s Journal Online, HERE,

and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube. If you have questions, as always, feel free

to leave a comment on either site. I

announce new articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds, on Instagram at

bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch for me.

That

is all for now, and as always, until next time, Happy Trails!

Notes

1 “AD

401819, Department of Army Approved Small Development Requirement for Individual

Aid and Survival Kit for Special Warfare”, page 1

2

Ibid. page 1-2

3

Ibid. page 1

4 “374659,

Employment Of A Special Forces Group (U)”, page H-6

5 Ibid.,

page H-5

6 Two

10-grain salt tablets, equal ¼ teaspoon (1.25 grams) of salt, which when

combined with a quart of water (.95 liter) creates a 0.1% salt solution, which

is the ideal concentration for rehydrating.

The salt tablets should be crushed before mixing them with water and

should not be eaten by themselves as they can irritate the stomach and cause

vomiting.

Eric

A Weiss, MD, A Comprehensive Guide To Wilderness & Travel Medicine,

3rd Edition

Sources

“AD

401819, Department of Army Approved Small Development Requirement for

Individual Aid and Survival Kit for Special Warfare”, [Reproduced

by Defense Documentation Center for Scientific and Technical Information,

Cameron Station, Alexandria, Virginia, Originally by the Headquarters United

States Army Combat Developments Command, Fort Belvoir, Virginia, April 17,

1963], https://ia902804.us.archive.org/19/items/DTIC_AD0401819/DTIC_AD0401819.pdf,

accessed September 14, 2018

“374659,

Employment Of A Special Forces Group (U)”, [Army Concept

Team In Vietnam, April 20, 1966], https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/374659.pdf,

accessed May 20 2020, page H-4 to H-6

United

States Army, ST 31-91B, US Army Special Forces Medical Handbook, [Paladin

Press, Boulder, Colorado, March 1, 1982], pages 11-1 to 11-2

Weiss,

Eric A, MD, A Comprehensive Guide To Wilderness & Travel Medicine, 3rd

Edition [Adventure Medical Kits, Oakland, CA, 2005], page 150-151

No comments:

Post a Comment