|

| An out-take from “The Elusive Cazenovia Bank Beaver, Part Two”, from BandanaMan Productions, HERE. |

Sometimes

it is easy to find evidence that there is a beaver in the area, particularly if

they have built a lodge or a dam, or gnawed a tree or two, but what if they are

the ever-elusive bank beaver, what should you look for then? And how do you know when you have found a den

site?

“Bank beaver”, you

ask “what type of beaver is that”?

That is a good question,

and you aren’t the first person to ask it.

After I posted the video, “The Elusive Cazenovia Park Bank Beaver, Part

One” on my YouTube channel, BandanaMan Productions, HERE,

I had several people ask what kind of beaver a bank beaver was. So, maybe I should first explain what a bank

beaver is.

Simply

put, a bank beaver is any beaver that lives in rivers or streams that are prone

to flooding1. Beavers in

these areas don’t build dams or lodges in the center of a pond, and just like

beavers living on large lakes, they live in a den that they have dug into the

bank.

Beavers

are prodigious diggers and will build several burrows in the banks of the

waterways that they call home, so that they are never far from a resting place

or a refuge. They also sometimes dig

tunnels far inland from the body of water that they call home, and where these

tunnels come up to the surface, a “plunge-hole” is created2.

“So,

how do I know that there is a bank beaver living in my favorite creek or river”,

you might ask?

The

first bit of evidence that you might see would be trees with fresh beaver-chews

on their trunks. You might also see a

beaver swimming up or down the waterway.

But finding evidence of their burrows is a bit harder.

|

| A beaver lodge built on the shore of a Cazenovia Creek, evidence of the ever-elusive Cazenovia Park bank beaver, photograph by the author. |

Sometimes,

bank beavers build a lodge, over their burrow and against the bank or shore of

the lake, creek or river that they are living on, and then it is easy to find

where they live, but sometimes they don’t.

When they don’t, you have to look for the vent-hole to find their burrow

or follow them as they swim and disappear into the bank, good luck on that!

|

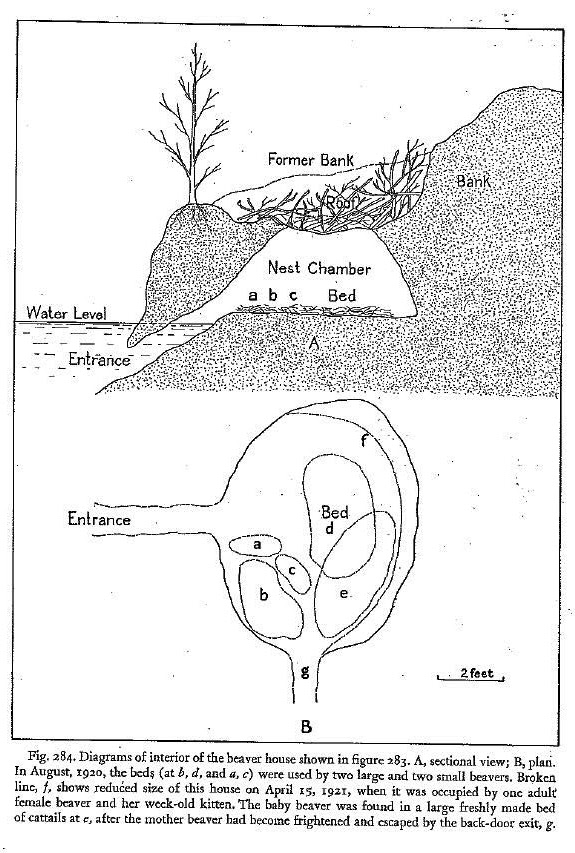

| A bank-burrow built under a tree and using the roots to support the roof, from the The Wise One, by Frank Conibear and J. L. Blundell, page 113. |

Bank

beaver’s burrows frequently have chambers that are close to the surface of the

ground, so that they can “breathe”. Many

times, because the roofs of these burrows are thin, they will collapse. Because of this, bank beavers often build their

burrows beneath the roots of a tree or a bush which will keep the top of the

burrow from caving in and still allow for ventilation. When the tops of the chambers collapse, the

beavers sometimes cover the collapsed area with a pile of logs and sticks, in

effect making a lodge on top of the ground.

The collapsed area and the pile of peeled logs and sticks become the

vent-hole.

|

| An abandoned bank beaver burrow, whose vent hole is covered with a sticks and logs, along Cazenovia Creek, in Buffalo, New York, photograph by the author. |

So

the next time you are walking along the bank of a creek or a river and you find

a pile of beaver peeled logs and branches, perhaps you have found the home of

the ever-elusive bank beaver.

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and look for me

on YouTube at Bandanaman Productions for other related videos, HERE.

Don’t forget to follow me on both The

Woodsman’s Journal Online, HERE,

and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube. If you have questions, as always, feel free

to leave a comment on either site. I

announce new articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds, on Instagram at

bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch for me.

That

is all for now, and as always, until next time, Happy Trails!

Notes

1

“...there are many beavers today that are living as bank beavers in places

unsuited to the construction of ponds, especially along streams and rivers that

are subject to floods.”

An

excerpt from Earl L. Hilfiker’s, Beavers: Water, Wildlife and History, page

117

2 “In many wooded areas of eastern Canada,

New York and New England, there are ponds and small lakes where, over the

years, vegetation has advanced far from the shore lines and covered

considerable expanses of water with a thick layer of sphagnum moss, pitcher

plants, sundew, and other types of acid-bog plants. These expanses of floating vegetation are

referred to as quaking bogs. Foot

progress across one of them is like walking on a mattress.

Beavers inhabiting some of these bodies of

water swim under rather than walk across them, and they cut holes in them where

they wish to come out. They may also

tunnel considerable distances inland before digging out above ground. The absence of dirt piles around these holes

indicates that the digging was done from below.

Except for the trails leading out from

them, it is often difficult to detect their presence, and it is surprising to

find how far some of them are from open water.

These holes make it easy for beavers to leave and return to the pond,

and when pursued by an enemy, a beaver can dive into one of these holes and

seek safety. For that reason, it may be

appropriate to refer to them as plunge holes.”

An

excerpt from Earl L. Hilfiker’s, Beavers: Water, Wildlife and History,

page 118

Sources

Conibear,

Frank and Blundell, J. L.; The Wise One,

[Petersen Engineering Co. Inc., Santa Clara, CA, 1959], p. 113

Grinell, Joseph, Dixon, Joseph S., Linsdale,

Jean M.; Fur Bearing Mammals Of California: Their Natural History,

Systematic Status, and Relations to Man, Vol. II, [The Museum Of Vertebrate

Zoology, University Of California Press, Berkeley, CA, 1937], https://martinezbeavers.org/wordpress/wp-content/docs/Fur-bearing%20mammals%20of%20California_%20their%20natural%20history_%20systematic%20status_%20and%20relations%20to%20man%20Vol.%20II%20Beaver%20chapter%20Grinne.pdf, accessed June 27, 2020

heidi08, “Bank Lodge e-VENTS”, June 13, 2012,

[Worth A Dam, © 2007-2018], http://www.martinezbeavers.org/wordpress/tag/beavers-wetlands-wildlife/

Hilfiker,

Earl L.; Beavers: Water, Wildlife and History, [Heart of the Lakes

Publishing, Interlaken, NY, 1990], p. 117-118

No comments:

Post a Comment