|

“Marley’s Ghost”, an excerpt from A Christmas Carol in prose. Being a Ghost-story of Christmas, by Charles Dickens, illustrations by John Leech, 1843, Wikimedia, HERE.

It

is almost Christmas and often at this time of year people post a Christmas

letter talking of the doings of the past year and wishing a Merry Christmas and

the best wishes for the coming year to their friends and those they love. Today, people of the 21st century,

simply fold the letter, slip it into a pre-made envelope and seal it with the pre-glued

flap and send it on its way with a stamp.

|

A letter sheet from 1628, opened up to show the folds, address and seal, with the letter written on the opposite side, from Wikimedia, HERE. Letter sheets were used until the middle of the 19th century.

But

this isn’t how it was always done. So, just how would Ebenezer

Scrooge have posted a letter?

To

write a letter like Ebenezer Scrooge in an authentic, late 18th and

early 19th centuries, period correct manner1 from the,

you need to find the correct size of handmade paper, you need to know about and

have a paper knife2, you must know how to fold and cut your paper

with your paper knife, and finally you need to know how to seal your letter

with either sealing wax or wafers.

“The most convenient form

for a letter, is a sheet of quarto paper...”

|

Folding and cutting a paper manufacturer’s full-sized sheet of writing paper, in half twice would provide you with a sheet of quarto paper, an excerpt from Writing & Illuminating, & Lettering, page 102-103

During

the late 18th and early 19th centuries letters were

written on what is today called a “letter sheet”. The Young Man’s Best Companion noted

that, “The most convenient form for a letter is, a sheet of quarto paper”. A sheet of quarto paper is piece of paper

that is one quarter of a manufacturer’s full-size sheet of writing paper,

folded and cut twice to provide four sheets of paper.

Unfortunately,

and obviously, the final size of a sheet of quarto paper depends on the size of

the original full-size sheet of the paper and manufacturers of the late 18th

and early 19th centuries made paper sheets in several different

sizes.

|

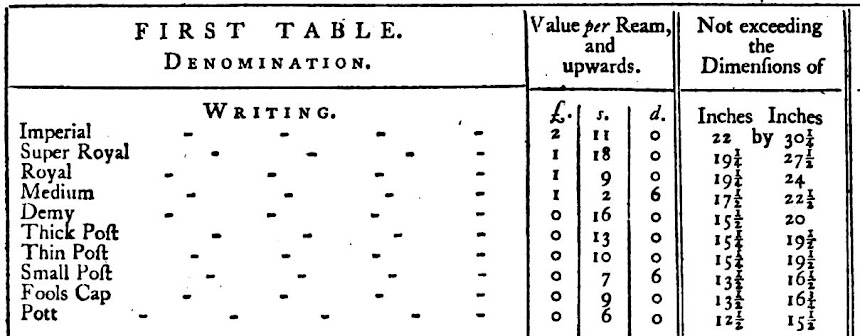

The sizes of manufactured paper, an excerpt from The Statutes at Large, Volume the Ninth, page 138.

During

the late 18th to early 19th century in England, and anywhere

else that used paper manufactured in Great Britain, “Medium” sized writing

paper, was 17-½ by 22-½ inches (44.5 by 57.2 cm), which when folded twice and

cut with a paper knife would make a four quarto sized sheets, that measured 8 ¾

by 11 ¼ inches (22.2 by 28.6 cm), which is almost the same size as modern 8-½ by 11 inches (21.6 by 27.9 centimeters) sheets of paper3.

Alternatively,

Melissa in “How to Post a Letter, 19th Century Style”, suggested using 11 by 17 inch (27.9 by 43.2 cm) paper on which to write

your late 18th and early 19th century letters. This would be a folio sized sheet of paper

and not a quarto sized sheet. However,

when you have folded this sheet down the center, each leaf would be quarto

sized.

|

Two different sized sheets of paper make two different sized folded letters, photograph by the Author.

I

folded a letter using both sizes of paper as a test and found that folding a

quarto sized sheet of paper in half, which creates an “octavo” sized leaf of

writing paper, makes for a small letter when it is folded around itself to seal

it. In the end I don’t know whose

interpretation is the most correct, Lady Smatter’s or Melissa’s, however based

on the excerpt from the Young Man’s Best Companion, I believe that Lady

Smatter is more correct. However, to be transparent,

for the following photographs I used a 11 by 17 inch

(27.9 by 43.2 cm) sheet of paper to create my letter.

To write your letter...

|

An excerpt from the Young Man’s Best Companion, page 64.

So,

to be period correct and write a letter as they would have in the late 18th

and early 19th centuries you could find some handmade paper of the

correct size, fold it, and cut it with a paper knife into quarto sheets and

start to write, or you could cheat and use a modern 8-½ by 11 inch (21.6 by

27.9 centimeters) or a 11 by 17 inch (27.9 by 43.2 cm) sheet of paper.

|

Folding your sheet of paper down the center to create a folio or booklet, photograph by the Author.

To

start your letter, take a sheet of paper and using your paper knife, fold it

down the middle into a booklet. When you

fold a quarto sized sheet in half to make a booklet, you make a two-leaf pamphlet

of four octavo sized pages. When you

fold a folio sized sheet down the center, you have a two-leaf booklet of four quarto

sized pages.

|

Your booklet of four pages, photograph by the Author.

According

to the Young Man’s Best Companion, letters were begun on the first page,

which is the front side or “recto”, of the first leaf, and you would write

on “three succeeding pages”, which would leave the fourth page, or the

backside or “verso”4, of the second leaf blank.

Don’t

forget “to leave on the middle of the margins of the third page, a space an

inch and a half square to receive the wafer or seal”. This space should be in the center of the “outer

margin”, the side of your booklet opposite the fold. If you forget to do this, when the recipient tears

or cuts the paper to open the letter, they will damage some part of the message

since, “the wax or wafer must be placed on part of the writing, which will

of course be destroyed”5!

Because

in England, during the late 18th and early 19th centuries,

it cost double to mail a letter in an envelope and in other countries it cost

an extra penny on top of the regular postage to post an enveloped letter,

people would leave the fourth page of their quarto booklet blank; so that it

would become, when folded, an envelope.

|

An excerpt from the Young Man’s Best Companion, page 64 to 65.

The most proper way to fold

a letter, written on quarto paper...

|

Folding a letter, an excerpt from the Young Man’s Best Companion, page 64.

To

fold a letter, so that the fourth page of the letter wraps around the other

pages, making a protective envelope; step one start by folding the top two

inches (5 cm) of the letter over. Step

two, fold up the bottom two inches (5 cm) of the letter. Step three, fold over the “inner margin”,

the side next to the center fold separating the leaves and pages, to within a

one and a half inches (3.8 cm) of the open “outer margin”, to make the

inner margin flap. Step four, fold over one

and a half inches (3.8 cm) of the “outer margin”, to make the outer

margin flap.

|

Here is how to fold your letter, Step One to Step Two, photograph by the Author.

Next

and last, tuck the inner margin flap into the folded over outer margin flap. The Lady Smatter recommends tucking the

closed inner margin flap into the outer margin flap, so that only the second leaf

(third and fourth page) of the folded over outer margin flap is sealed to inner

margin flap, this way only the space that you left in the “outer margin”

of page three will be torn away when the letter is opened.

|

The inner margin flap tucked into the outer margin flap, photograph by the Author.

Addressing and sealing the

letter...

|

An excerpt from the New Complete English Dictionary ...: Wherein Difficult Words and Technical, John Marchant Gordon, 1760.

Now,

seal your letter with either wafers, which were small, dry paste disks6,

or with sealing wax, where the inner and outer flap come together. You can also cheat if you are not concerned

with historical accuracy and use a sticker.

|

The opened letter, showing the seal, the address the return address and the torn portion of the outer margin when the letter was ripped open, photograph by the Author.

Because

of how the letter is folded, both addresses are written on the fourth page, which

is the backside or verso of the second leaf, the return address should be

written just above the seal and the recipient’s address on the opposite side of

the folded letter.

|

A completed letter, ready to be posted, photograph by the Author.

For

a video on how to fold a letter into own envelope, watch “Posting a Christmas

Letter Like Old Ebenezer Scrooge ©”. HERE.

I

wish you a Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays and the very best wishes for the

coming year!

Don’t forget to come back next week and read “Burn This Book! ©”,

where we will talk about how to improvise, adapt and overcome, when misplaced

in the wilderness.

|

Outdoor Survival Skills, by Larry Dean Olsen, photograph by the Author.

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and look for me

on YouTube at BandanaMan Productions for other related videos, HERE. Don’t forget to follow me on both The

Woodsman’s Journal Online, HERE,

and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube. If you have questions, as always, feel free

to leave a comment on either site. I

announce new articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds, on Instagram at

bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch for me.

That

is all for now, and as always, until next time, Happy Trails!

Notes

1

Little did I know when I started this article that the practice of letter

writing had changed so drastically in the last 175 years. Lady Smatter, who writes about Jane Austen

and England during the Regency Period of 1811 to 1820 in her blog, Her Reputation

for Accomplishment, has done an impressive job of researching and writing about

letter-writing during the late 18th and early 19th

centuries. She has published twelve

articles, all of which can be found HERE. Also the article “Anatomy

of a Regency Letter”, HERE,

is a good introduction which talks about the size of writing paper during this

period.

2

|

The Author’s paper knife, photograph by the Author.

A

“paper knife” is not the same as a “pen knife”. A pen knife has a sharp point and a short,

sharp blade and was used to sharpen the nibs of quill pens and later

pencils. A paper knife was a knife that

had a rounded tip and a blade with a smooth, rounded edge, which was perfect

for cutting through the paper fibers that had already been weakened by folding. In fact, the flat of the paper knife blade

was often used to create a sharp fold, which could then be cut by the edge of

the paper knife.

See

also “A Paper Knife Was Not a Letter Opener” by Kathryn Kane, the author of The

Regency Redingote

3 According

to Lady Smatter, in her article “Anatomy of a

Regency Letter”, the common size of a sheet of quarto letter paper “could

range in size from somewhat larger than standard 8.5×11 inch paper (A4 paper if

you’re not in the US) to somewhat smaller”.

In fact, a common size of paper was “Post” paper, which measured 15 ¼ by

19 ½ inches (38.7 by 49.5 cm), and which when folded and cut into quarto sheets

would have produced four sheets of paper which each measured 7-5/8 by 9-¾

inches (19.3 by 24.7 cm)

4 According

to Tate.org, HERE,

“The front or face of a single sheet of paper, or the right-hand page of an

open book is called the recto. The back or underside of a single sheet of

paper, or the left-hand page of an open book is known as the verso”.

5

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, letter

openers would sometimes use an “erasing knife” to break or lift the

seal. An erasing knife was a short sharp

knife like a modern X-ACTO® knife which could be used to gently scrap away

stray ink marks off the surface of the paper or to slide under the sealing wax

or wafer

6

For information on how to make sealing wafers and the etiquette of when to use

sealing wax instead of sealing wafers, go to Lady Smatter’s “Making (and

Faking) Wafers”, HERE,

“Sealing with Wafers”, HERE,

and “Wafer Etiquette”, HERE.

Sources

Baston, Karen; “William

Hunter’s Library: the Shapes of Books”, October 9, 2017, https://universityofglasgowlibrary.wordpress.com/2017/10/09/william-hunters-library-the-shapes-of-books/, accessed December 11, 2021

Gordon,

John Marchant;

New Complete English Dictionary ...: Wherein Difficult Words and Technical,

[Printed for J. Fuller, London, 1760], page QUE to QUE, https://books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5QaeHpTY7Pr8JOpxvhlRXWof1PzrerMFqiQcMVANexSBNYb74NelytLzFcgLkB1mSly47jg5InpBJ7EJ7PbJ2aWha9I-nXdU1e6DViBBZ4U12cy_rDykThiDtV5tSE5NO4TtWcJD_De0N558vG6yGO10LSA9lnwnw7k_W8we4pJACi3MXjGvbowUHa5MHf6NFBp7eOez34QgiXpM62246Fx3v_tdts5HXu4HmhdDXRAMQtfWlS5DNGq0IcR825m6ywDC4U8fwY_luALl9r-b_MA8GsPa86w, accessed December 15, 2021

Johnston, Edward; Writing

& Illuminating, & Lettering, [Published by John Hogg, London],

page 102-103, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/47089/47089-h/47089-h.htm, accessed December 11, 2021

Kane, Kathryn; “A Paper

Knife Was Not a Letter Opener”, The Regency Redingote, May 24, 2013, https://regencyredingote.wordpress.com/2013/05/24/a-paper-knife-was-not-a-letter-opener/,

accessed December 16, 2021

Lady Smatter, “Anatomy of

a Regency Letter”, Her Reputation for Accomplishment, May 6, 2015, https://herreputationforaccomplishment.wordpress.com/2015/05/06/anatomy-of-a-regency-letter/, accessed December 11, 2021

Melissa, “How to Post a Letter, 19th Century Style”, February

14, 2011, [© Iowa State University Library Preservation Department, 2021], https://parkslibrarypreservation.wordpress.com/2011/02/14/how-to-post-a-letter-19th-century-style/,

accessed December 11, 2021

The

Statutes at Large, Volume the Ninth,

[Printed by Charles Eyre and Andrew Strahan, London, 1776], page

138, https://books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5Qaez-3CYllslnIpD9vsc7LD9eVGbyVFLHFUyzh1oeW5jAdnPTWFNwJ8aQfbLxIe2IDrv4_CTbWZUs5UvHRMtaqxQfhmXni1SnSYRsruJpmelfJhwCWpIXEZcpdsOy7kycOk0_ViB82dz9ZYu9rVNXTI2Q_0luGKKz9aRIEr1S_BJCX4_BtnXfjoyAee8_j_hWGl8L17IBmpllF1Ht_5V_3egxFu_MOSPRQ5nTOTCeUlOqnPu20Ra-tJMGGTbdIo3IB1YNjImkfCbLup7IPi_k7hq2UJiG7s20i4mkpjUCBiPxqPhV4E,

accessed December 15, 2021

Wikimedia, “Opened up

1628 lettersheet”, by Albrecht von Waldstein, 1628, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WallensteinBriefSiegel.jpg,

accessed December 11, 2021

Wikimedia, “Marley’s

Ghost”, by John Leech, illustrator, from A Christmas Carol in prose. Being a

Ghost-story of Christmas, by Charles Dickens, [1843], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marley%27s_Ghost_-_A_Christmas_Carol_(1843),_opposite_25_-_BL.jpg,

accessed December 11, 2021

No comments:

Post a Comment