For

centuries, usually without success, armies have attempted to reduce the weight

that their soldiers carried into battle and to evenly distribute it over the

soldier’s body in such a way as to be both conveniently carried and to not

impede the soldier’s ability to march and fight.

For

centuries, usually without success, armies have attempted to reduce the weight

that their soldiers carried into battle and to evenly distribute it over the

soldier’s body in such a way as to be both conveniently carried and to not

impede the soldier’s ability to march and fight.

It

is a curious fact that during the last part of the 19th century, the

U.S. Army quietly shelved the knapsack, allowing soldiers in the field to

replace it with the blanket roll.

During

the American Civil War both sides issued knapsacks, the

Union Army issuing the M-1855 and later the M-1864 “Double Bag” knapsack. Later, during the campaigns on the western

plains against the Native Americans, the U.S. Army issued the experimental M-1878

“Blanket Bag” knapsack to the soldiers and, although it was never officially

adopted, it was used until the M-1910 series of accouterments were approved by

the military. This knapsack weighed just

over 2-½ pounds, or just over 1.1 kg, empty with its straps and could hold 990

cubic inches or 16,223 cubic cm1.

However,

early in the American Civil War, veterans on both sides lightened their loads

and discarded their knapsacks, often

However,

early in the American Civil War, veterans on both sides lightened their loads

and discarded their knapsacks, often

abandoning them alongside the roads, and

carried a change of drawers, socks and other necessaries rolled up into a

blanket and slung over their shoulder. Even

though a blanket roll, or as it was also known the “horse-collar roll” (from

its likeness to a piece of a horse’s harness) could be hot and its weight

across the chest could impede breathing, soldiers both during the Civil War, and

later up to 1910, used it almost exclusively to carry their necessaries.

From

1861 until 1910, American soldiers went into the field with their shelter half,

blanket and personal gear all rolled up and slung over their shoulders. However, it should be remembered that the

military’s acceptance of the blanket roll did not imply approval, because as a

military panel stated in 1889 “such use [during the civil war] did

not imply an approval of the roll, so much as a condemnation of the knapsack

then provided for the troops”.

Additionally, the same source noted that the order discarding the

blanket bag and authorizing the official use of the blanket roll is only “...until

some more satisfactory method of carrying the pack has been devised”2.

|

An M-1878 pattern “Blanket Bag” knapsack, collage

compiled by the Author. |

But why...?

So why did the U.S. Army allow the use of the blanket roll by soldiers in the field?

Simply

put, American soldiers refused to carry anything more than

Simply

put, American soldiers refused to carry anything more than

was required to

accomplish their mission, and they did not like, as one soldier of the time

expressed it, to be “trussed like pack mules”3. A veteran of the campaigns against the Native

Americans in the 1870s further declared, “The knapsack containing clothes

the soldier can get along without, seems to him an additional burden that is

better off to lose than to waste his strength carrying”.4 In the end, the U.S. Army bowed to the

inevitable and did not require that soldiers use of the knapsack and even at

times expressly ordered the use of the blanket roll in the field, because as

Captain Arthur MacArthur stated “The blanket roll, however, in its various

forms, as used by the soldiers of the Civil War, is of greater utility than any

other contrivance for carrying the necessities of a campaign; & men will

never, excepting under compulsion of absolute authority, carry an equipment

that weighs in itself as much as a day’s rations. My judgement is against the use of any

knapsack”.5

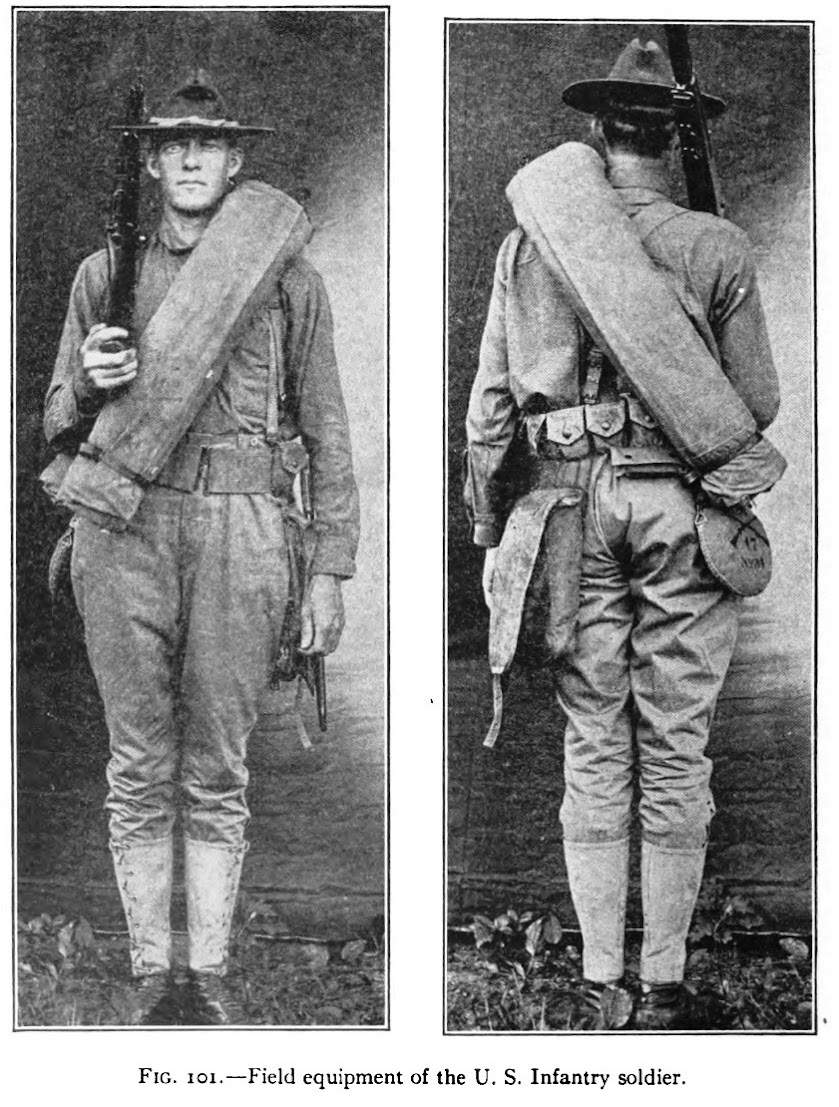

A photo of U.S. Army soldier, circa 1909, an excerpt from Manual of Military Hygiene, page 262.

But

why did American soldiers dislike their knapsacks? According

Captain N.D. Walker, as noted in the Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corp,

during the American Civil War, soldiers thought that

But

why did American soldiers dislike their knapsacks? According

Captain N.D. Walker, as noted in the Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corp,

during the American Civil War, soldiers thought that

the knapsack was a heavy,

and that “...it was found to gall the back and shoulders and weary a man

before half of the march was accomplished”.6

The knapsack and straps when empty, were heavy, weighing just over 2-½ pounds, about 1.1 kg, which is about the weight of a day and a half’s ration of bread and meat. Carrying a knapsack, just to hold things that you that you could easily carry by themselves, simply didn’t make sense to the soldiers.

Also,

the pack straps galled the skin and compressed the nerves and muscles of the

shoulders and chest. Both the M-1855 and

the later M-1864 “Double Bag” knapsack, had straps that connected near the

center of the bag, allowing it to swing from side to side, irritating the

shoulders and back, and to sag, which put pressure on the lower back. The M-1878 “Blanket Bag”, since its straps

were attached to back of the knapsack directly in line with the wearer’s

shoulders, did not have these problems.7

Also, soldiers of the late 19th

century, found their knapsack to be tiring to carry, compared to the blanket

roll. One of the problems of a knapsack

of the time, was that it was top heavy with the knapsack near the back of their

necks and shoulders. This shifted the

center of gravity backwards, forcing the soldiers to lean forward to bring

their center of gravity back over their feet, and this made marching tiring.

The blanket roll, by distributed the

weight of the soldier’s equipment more evenly over their body, did not pull

them backwards, making marching less tiring.

And while the blanket roll could impede breathing and be hot to carry,

especially in warm climates, it was less galling to the back and

shoulders. Taken all together it is no

wonder that the foot soldiers of the U.S. Army of the late 19th

century insisted on carrying the blanket roll.

Making a

Blanket Roll, Late 19th Century Style

Making a blanket roll, an excerpt from the Army and Navy Register, June 10, 1905, by the Adjutant General of the Minnesota National Guard, page 27.

So,

how did the soldiers of the late 19th century roll a blanket roll?

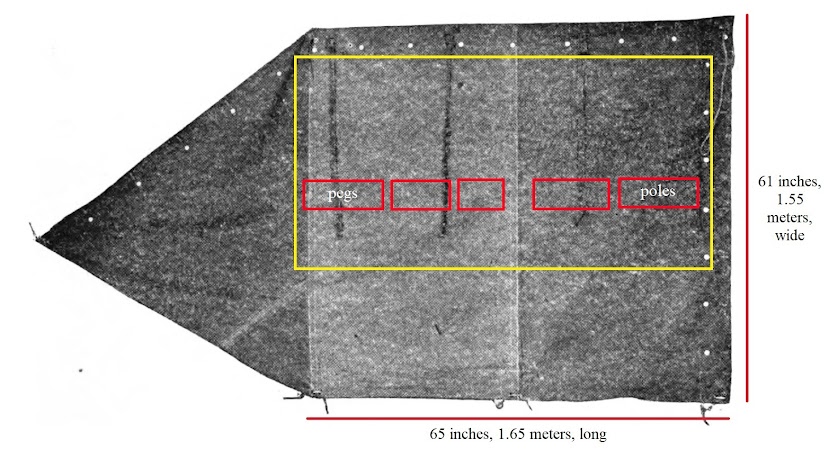

The

shelter half is about 65 inches, 1.65 meters, long, by 61 inches, 1.55 meters,

wide, and weighs, when dry, about 2 ½ pounds, or 1.1 kg. Shelter halves were originally made using the

pattern of the d’Arbi tent of the French Army, and during the American Civil

War were called “pup tents”, by Union soldiers, on account of their shape and

small size.7

Shelter

half tents made in the latter part of the 19th century, such as the

shelter patented by Edmund Rice in 1896, HERE,

had straps along the border to help keep the blanket roll compact. If a

soldier didn’t have a shelter half and instead was using a piece of canvas, he

would need three or four strings with which to tie the blanket roll tight, and

another longer one (typically the guy rope, which was 3/8

inches, 9.5 mm, in diameter) to hold the two ends together when the roll is

folded into a loop.

Lay

the shelter half out smoothly on the ground, with the buttons up, towards the

top, and the triangular end to the front or right, like in the picture

below.

The shelter half laid out flat with the buttons up, note the four straps sewn on the underside. An excerpt, modified by the Author, from Manual of Military Hygiene, page 263.

Step Two:

Soldier’s

blankets during the late 19th century were 7 feet, 2.1 meters,

across the long side and 5-½ feet, 1.7 meters, across the top and weighed 5

pounds, 8 ounces, or 2.5 kg.

Soldier’s

blankets during the late 19th century were 7 feet, 2.1 meters,

across the long side and 5-½ feet, 1.7 meters, across the top and weighed 5

pounds, 8 ounces, or 2.5 kg.

Fold

the blanket once across its length, so that the long side is now 3-½ feet, 1.07

meters, long. Place the blanket it on

top of the shelter half, just inside the buttons on the top and right, with the

fold towards the bottom, unbuttoned side; the blanket should cross the seam

attaching the triangular end of the shelter half. This way there will be at least a ½ inch, about

a 1 cm of canvas uncovered on both the right or square side and the buttoned or

top side of the shelter half.

An excerpt, modified by the Author, from Manual of Military Hygiene, page 263.

Step three:

An excerpt, modified by the Author, from Manual of Military Hygiene, page 263.

Next,

lay the parts of the pole on the right side of the blanket, towards the square

side of the of the shelter half, about six inches, 15 cm, above and parallel to

the fold. Now place the five tent pegs

on top of the blanket, about six inches, 15 cm, above

and parallel to the fold, on the left or triangular end of the shelter

half. Last distribute your clothes and

necessities across the rest if the blanket, again about six inches, 15 cm,

above and parallel to the fold. Don’t

place anything hard or sharp in the middle of the blanket or it will gall your

shoulder.

Step 4:

An excerpt, modified by the Author, from Manual of Military Hygiene, page 263.

Next

fold the left or triangular end of the shelter half over the blanket, and then

fold the bottom canvas up and over the blanket.

Now tightly roll the blanket and canvas, towards the top or buttoned

side of the shelter half. The Adjutant

General of the Minnesota National Guard, in the Army and Navy Register,

suggested having you and your “pard”, the name for the person sharing your

shelter half, roll together, side by side, to get a tight roll. When it is rolled, either buckle it together

with the four attached straps , or tie it tightly with string.

Lastly,

with edge of the shelter half just visible as you are looking straight down at

the roll, (this way the seam doesn’t rub your neck or shoulder) bend it into a

“U” and tie a clove hitch with the guy rope, first around the end to which it

is attached and then around the other end, adjusting the length of rope between

the hitches to suit the wearer. Place it

over your head resting on your left shoulder.

You now have all your essential gear in a nice neat, simple roll that

only weighs 12 pounds, 2 ounces, or 5.5 kg.

An example of the items contained in a blanket role and its overall weight, excerpt from, Noncommissioned Officers' Manual, Captain James A. Moss, page 410.

An

important note, some authors recommended placing your ground sheet or poncho

between your blanket and your shelter half, a problem with this is, if it rains

you will have to undo the entire roll to get to your rain gear. Other authors advocated keeping it available,

by carrying it outside of the blanket roll.

So why is

it important today?

Okay,

most of us are not reenactors of the American Civil War or the Spanish American

War, so why is this important to the modern reader?

Because

there might be times, when you are “misplaced” in the wilderness in a survival

situation, and you need to move. Maybe,

it has been more than three days and you are afraid that the searchers can’t

find you, perhaps you need to move to a more visible spot or to a spot with

more water, food, firewood, etc. For

whatever reason you don’t have a knapsack, but you might have a blanket, a

piece of canvas or even a piece of plastic, but because you know how to make a

blanket roll, you know how to carry your important survival supplies.

Don’t forget to come back next week and read “Your Center of Gravity and

Why it is Important©”, where we will talk about how to carry your gear and

distribute the weight so that it isn’t so tiring.

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and look for me

on YouTube at BandanaMan Productions for other related videos, HERE. Don’t forget to follow me on both The

Woodsman’s Journal Online, HERE,

and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube. If you have questions, as always, feel free

to leave a comment on either site. I

announce new articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds, on Instagram at

bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch for me.

That

is all for now, and as always, until next time, Happy Trails!

Notes

1 A

Reference Handbook of the Medical Sciences, Volume 5, edited

by Albert Henry Buck, MD, page 797

2 Ibid.

3 Uniforms,

Arms, and Equipment: Weapons and accouterments, by Douglas C., McChristian,

pages 9 to 35

4

Ibid.,

5 Ibid.,

6

Journal

of the United States Artillery, July-August 1899, “Rice’s Shelter-tent Half,

Blanket Roll and Rain Cape”, by Staff of the Artillery School; pages 60-66

7

From the Quartermaster Support of the Army, a History of the Corps, by

Erna Risch, pages 359 to 360

Sources

Adjutant

General of the Minnesota National Guard; Army and Navy Register, June

10, 1905, Vol. XXXVII, No. 1330, [Washington D.C., June 10,

1905], page 27, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Army_Navy_Air_Force_Register_and_Defense/a1A-AQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=spanish+american+war+%22shelter+half%22&pg=RA22-PA27&printsec=frontcover,

accessed November 29, 2022

Buck, Albert Henry, MD,

Editor; A Reference Handbook of the Medical Sciences,

Volume 5, [William Wood and Company, New York, NY, 1902], pages 797 to 818, https://books.google.com/books?id=JpQplgCyEC0C&pg=PA797&dq=weight+%22blanket+bag%22&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiwz9mRodz7AhUhKFkFHfBsAF4Q6AF6BAgFEAI#v=onepage&q=weight%20%22blanket%20bag%22&f=false,

accessed December 2, 2022

Google

Patents, “E. Rice Shelter Tent”, Patent No. 573918, December 29, 1896, https://patents.google.com/patent/US573918, accessed November 28, 2022

Gould, John M.; Hints for

Camping and Walking, [Scribner, Armstrong & Co., New York, NY, 1877] page

17, https://books.google.com/books?id=PE4MAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA17&dq=blanket-roll+1877+goulds&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjbwN7X44v7AhUsKFkFHT51A6MQ6AF6BAgJEAI#v=onepage&q=blanket-roll%201877%20goulds&f=false,

accessed November 30, 2022

Harvard,

Valery, MD; Manual of Military Hygiene, [William

Wood and Co., New York, NY, 1909], pages 255 to 257, and 261 to 264, https://books.google.com/books?id=DlA3AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA262&dq=%22field+equipment+of+the+U.S.+infantry+soldier%22+1909&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjhq_G74Yv7AhUJD1kFHf8cDEcQ6AF6BAgHEAI#v=onepage&q=%22field%20equipment%20of%20the%20U.S.%20infantry%20soldier%22%201909&f=false, accessed November 29, 2022

Headquarters Army Air

Forces; Emergency Uses of the Parachute, AAF manual No. 60-1,

[Washington D.C., February 1945], page 4 to 5

Hinman,

Wilbur F.; Corporal Si Klegg and his “Pard”,

[The N. G. Hamilton Publishing Co., Cleveland, Ohio, 1895], page 160, https://archive.org/details/corporalsiklegg00hinmgoog, accessed December 1, 2022

Huidekoper, Frederick Louis; “The Lessons of Our Past

Wars”, The World’s Work, February 1915, Vol. XXIX, No. 4, [Doubleday, Page

& Co., 1914 , 1915], page 398, https://books.google.com/books?id=y5zNAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA398&dq=%22it+weighs+nearly+ten+pounds+less+than+the+old%22&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjD5rq14Iv7AhVHF1kFHf8LAdQQ6AF6BAgHEAI#v=onepage&q=%22it%20weighs%20nearly%20ten%20pounds%20less%20than%20the%20old%22&f=false, accessed November 29, 2022

McChristian, Douglas C.; Uniforms,

Arms, and Equipment: Weapons and accouterments, pages 9 to 35, https://books.google.com/books?id=XR_oRjNZFxsC&pg=PA17&lpg=PA17&dq=M-1878+%E2%80%9CBlanket+Bag%E2%80%9D&source=bl&ots=PoONlYzp4-&sig=ACfU3U2MmTgZ5S7QS6h4NUjzzUR0VdLvsg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjgwf6Tu9v7AhWNMVkFHSbwCIY4FBDoAXoECBYQAw#v=onepage&q=M-1878%20%E2%80%9CBlanket%20Bag%E2%80%9D&f=false,

accessed November 29, 2022

Moss, Captain James A.; Noncommissioned

Officers' Manual, [The George Banta Publishing Co., Menasha, Wisconsin,

1909], page 250, https://books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5Qac9Vc_m_Q76tNChMziOP0F3yovN9PmSIrSbazDsdBf_WuDwMSqQJTA6yIWaOM3ocQeXni7KOAutngEy1mCKC_B7qD6xKiyVNIclibGBS1nFWdT9Ogc29SEqlpb_I0s3NEFYL5uW9GrwFw7nEU-71uRw5UT4v7141wFxDGCOuSD_a-tHmse6NT2IRm9GdI5S9R_bWgbJEvHSRHfBRgLAf_Shjfe-H97rAfKS-ejBxW_tpW8vNUMu-U-yFhaB6VnrQidakTyLXaAxpipboW96WUzzDhT5Vg,

accessed November 29, 2022

Risch,

Erna; Quartermaster Support of the Army, a History of the Corps, [Quartermaster

Historians Office, Washington D.C., 1962], pages 359 to 360, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Quartermaster_Support_of_the_Army_a_Hist/Ud8fejE_4XkC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=spanish+american+war+%22shelter+half%22&pg=PA791&printsec=frontcover,

accessed November 29, 2022.

Staff

of the Artillery School; “Rice’s Shelter-tent Half, Blanket Roll and Rain

Cape”, Journal of the United States Artillery, July-August, 1899, Vol.

XII., No. 1, Whole No. 39; [Artillery School Press, Fort Monroe, Virginia,

1899], page 60-66, https://books.google.com/books?id=XhQDAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA1-PP11&dq=%22journal+of+the+united+states+artillery%22+%22volume+xii%22+1899&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwietpaPr8P7AhW4EVkFHThTBxcQ6AF6BAgHEAI#v=onepage&q=%22journal%20of%20the%20united%20states%20artillery%22%20%22volume%20xii%22%201899&f=false, accessed November 22, 2022

No comments:

Post a Comment