For my readers who are

Boy Scouts in the United States, this article can help you with First Class

requirement 3d, “Use lashings to make a useful camp gadget or structure” –

Author’s Note.

“It

will be dark in an hour, it looks like rain and I am lost”, you think, as

you start to panic! “No, stop, wait a

second, remember that post on The Woodsman’s Journal Online, it said that you

are only as lost as you think you are”, you say to yourself, as you try to

calm yourself down. “It’s going to

rain ... first things first, I need a shelter ... I have a poncho, but how do I

make a survival tripod”, you wonder as you begin to list your survival

priorities?

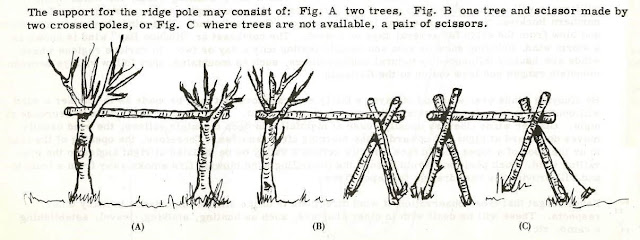

If

you are lucky, the easiest way to build a quick shelter is to find one or two

pieces of forked ground wood that are right length and thickness, to serve as

spars or legs, which you can prop up against the trunk of tree or against each

other and another length of wood to make a tripod. I say “do you feel lucky” because, if

you are in an emergency-situation or you are injured it might be difficult to

find ready-made, naturally forked lengths of wood of the size that you need1.

You

should never trust to luck in an emergency because, that is when luck will

desert you, and that is why you should know how to build a survival tripod, which

you can build by lashing three spars together with string2.

With

a tripod you can either build a tepee-style shelter, a long lean-to shelter

(Fig. 1, below), or a 3-pole lean-to (Fig. 2, below), depending on your needs

and what you have to go over it.

The

easiest and simplest way that I have found over the years to rig up a quick, easy,

and sturdy tripod is with the “tripod lashing for light structures” as taught

by the Boy Scouts of America.

|

| Step One of tying a tripod lashing for a light structure, using a 55 inch (140 cm) long shoelace, photograph by the author. |

While

holding the spars or legs of your tripod together, place the beginning of the

rope in the groove between two of the legs and then wrap over the rope end and

down towards the base of the legs a couple of times, until you are near the end

of your rope.

|

| Step Two of tying a tripod lashing for a light structure, pushing the end of the shoelace up the groove that contains the beginning of the shoelace, photograph by the author. |

Push

the end of your rope, up the groove that contains the beginning of your rope

and then tie the two ends in a square knot, right over left, and then left over

right.

|

| Step Two of tying a tripod lashing for a light structure, tying the square knot in the shoelace, photograph by the author. |

|

| Step Three of tying a tripod lashing for a light structure, opening the legs of the tripod into a tepee-style shelter, photograph by the author. |

|

| Step Three of tying a tripod lashing for a light structure, opening the legs of the tripod into a 3-pole lean-to, photograph by the author. |

Open

the legs of your tripod into whatever shape your shelter calls for.

|

| Step Four of building the tepee-style shelter, putting extra supports onto the tripod, photograph by the author. |

|

| Step Four of building the tepee-style shelter, putting the author’s Swiss-made rain cape onto the tripod to make a shelter, photograph by the author. |

“Okay,

I have a shelter to wait out the rain, now all I have to do sit tight until

morning”, you say to yourself, “I think I should be alright...”

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and look for me

on YouTube at Bandanaman Productions for other related videos, HERE.

Don’t forget to follow me on both The

Woodsman’s Journal Online, HERE,

and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube. If you have questions, as always, feel free

to leave a comment on either site. I

announce new articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds, on Instagram at

bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch for me.

That

is all for now, and as always, until next time, Happy Trails!

Notes

1

If you remembered to bring a hatchet or a belt knife with you, you could always

cut saplings and branches to fit, but if not, you are going to have to depend

on luck to find the right size piece of ready-made, naturally forked wood for

the spars or legs of your shelter.

2

That

is, provided of course, that you have some string or rope, which is one of the

rarest of items in a survival situation and you should always, always carry

some with you. However, unless you are

Cody Lundin, you are probably wearing shoes and that means you do have some

string with you, your shoelaces. You

should still always have some around your wrist, around your Nalgene bottle, in

your survival kit or pocket, just in case you need to use your shoes and make a

shelter, at the same time.

Sources

Boy

Scouts of America; Knots And How To Tie Them, [Boy Scouts of America,

2002 printing of the 1978 Edition], page 30

Innes-Taylor,

Alan; Arctic Survival Guide, Scandinavian Airlines Systems, Stockholm,

Sweden, 1961], page 54-58