|

Photograph taken November 12, 2017 in the Allegheny Highlands, this rock shelter faces west to southwest and is within 300 feet (approximately 90 meters) of the summit of a 2,100 foot (640 meter) high hill. Note that the fire is small and built against a reflector under the “drip line” of the overhang. From the Author’s collection.

The

two articles in this series, can be used by Experimental

Archaeologists, Re-enactors or Historical Trekkers of the late 18th

and early 19th centuries, and by people who are interested in

wilderness survival. For a video, watch “Sleeping

Rough Old-School: How to Overnight in a Rock Shelter ©”, HERE.

You

can read “Part One”, HERE.

However,

first a word of caution. While I

carefully research the subjects that I write about and practice them in the

field1, and though I like to think that I know more than most, I am

not an expert. Also, adventuring in the

wilderness, in general, is an inherently dangerous and risky proposition, and

while there are ways of reducing the risks, they can never be 100%

eliminated. In the end it comes down to

reducing your risks and then weighing the risks of the choices in front of

you. The information in this article is

intended to educate and inform you.

However, the decisions that you make with this information are yours and

yours alone: the author accepts no responsibility or liability for your actions

or their outcomes – Author’s note.

Maybe

you are a re-enactor enjoying a trek through the woods, maybe you have been out

for a day hike. But either way, you realize

that you are “misplaced” and evening and a storm are fast approaching. It looks like you are going to have an “unexpected

overnight” – you need a shelter and a fire, NOW! In the distance you spot a shallow cave or

rock shelter2

at the base of a small cliff.

Should you shelter in that rock

shelter for the night? Is it safe, what

should you look for and what should you do?

Remember,

one of the first rules of survival is “Do Not Waste Precious Energy”. And remember, even if there are a few wet

spots or drips in the rock shelter, it is better being under shelter than being

out in the rain. So, always look for a

natural shelter, rather than spending time and energy making one.

|

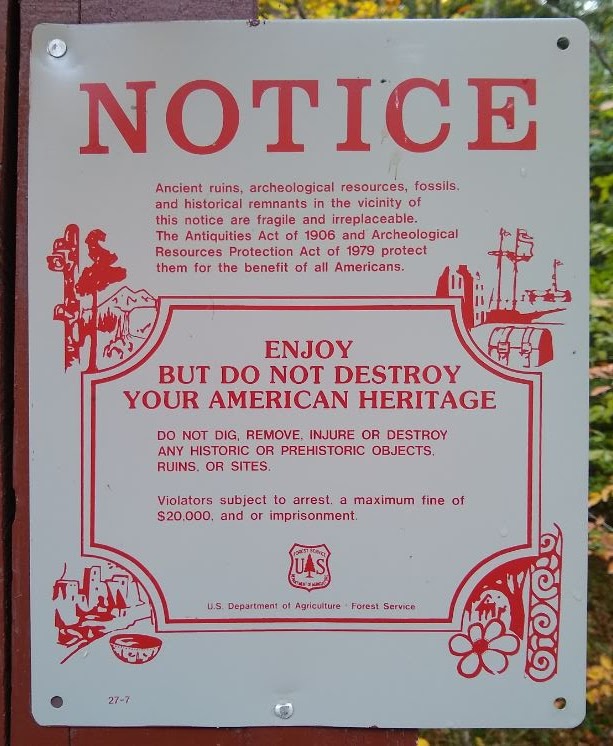

A

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service notice,

photograph by the author |

Before we go any further,

many rock shelters are archeological sites that have been used as shelters by

wanderers for thousands of years. You

should not overnight in them unless it is an emergency, or you have permission

from the landowner. In any case, while

sheltering in one you must NOT disturb, deface, or dig up anything! Digging up or looting arrowheads or pottery,

disturbs the seeds, pollen grains, animal bones and soil stratigraphy that

allows us to study of the past and it steals from the future – SO DON’T DO

IT! If you see someone or find evidence

that someone has been digging, disturbing, or defacing a rock shelter, contact

the landowner. Also, if you find

something on the ground underneath a rock shelter, that seems to be archaeologically

important, leave it where it is and contact the landowner to report it.

|

Photograph taken November 12, 2017 in the Allegheny Highlands, this rock shelter faces west to southwest and is within 300 feet (approximately 90 meters) of the summit of a 2,100 foot (640 meter) high hill. From the Author’s collection.

I would like to say that

there is a lot that has been written about how to overnight in a rock shelter,

but unfortunately there isn’t, and much of what is written is both half right

and half wrong. To my knowledge, very

few modern wilderness and survival writers have bothered to review the

archaeological reports, which detail prehistoric and historic occupancy of

these shelters, to find out how they were actually used in the past. In my mind this is a problem because our

ancestors were pretty smart and could definitely teach us a thing or two about

surviving in the wilderness.

There are two questions

that you need to answer before you decide to spend a night in a rock shelter. The first question is, is it already

occupied?

Rock shelters are valuable real estate, so always

check for inhabitants: study the inside of the shelter carefully and look and

listen carefully before you go inside. Shelter

dwellers can include, depending on where you are, wild cats, bears, bats, rodents

of all types, snakes, scorpions, and wasps.

In the spring and summer listen for the sounds of young animals. During the fall and winter, beware of denning

or hibernating animals.

Shine a flashlight into the shelter but beware

because bats and most snakes won’t react to a flashlight beam. If you can, use a flaming torch instead,

since snakes and bats will react to the heat and flames of the torch. Look for scat or bat guano on the floor of

the rock shelter, it is a sure sign that it is already occupied. Throw some rocks or sticks into the rock

shelter, snakes are sensitive to vibrations and it should bring them out.

Once you have determined that the shelter is unoccupied, then the second question is, is it safe?

|

Photograph taken October 12, 2020 in Minister Valley, in the Allegheny Highlands. Note the large boulders, which have fallen from the roof of this overhang, at some point in the past. From the Author’s collection.

You

should always check to make sure that the overhanging roof is stable and not

going to come crashing down on you while you sleep. Start by looking at the floor of the shelter,

if there are large boulders or stones on the floor, then the roof might be

unstable. Next bang on the ceiling with

a heavy branch or a walking stick and listen for a hollow or dull sound. If you hear one it means that the ceiling

might have a crack or a loose section. Also,

look for trickles or piles of small stones or sand, these are signs of an

unstable roof.

Look

to see if your rock shelter is at the base of a small cliff or is in a heavily

wooded area Rock shelters formed at the bottom

of tall cliff can be dangerous during a thunderstorm, because lightning

travelling down the cliff face, past the cave opening, and can travel through

the air where you are sitting. Rock

shelters that are at the base of a small cliffs or low outcroppings of rock or

are in a heavily wooded area are relatively safe from lightning.

However,

remember that while you can reduce your risk from falling rocks or lightning

strikes, you can never totally eliminate it, and you are never 100% safe.

|

A few icicles are okay. Photograph taken November 12, 2017 in the Allegheny Highlands, from the Author’s collection.

Look

for drips of water, or icicles in the winter.

A few drips or icicles are to be expected, but if the shelter is very

wet, even when the weather is dry, or if there is a lot of ice inside the

shelter in the winter, then a spring might be leaking through the rocks. Don’t camp in a very wet rock shelter,

because if there is a storm you might get washed out.

|

Photograph

taken November 23, 2016 in Minister Valley, in the Allegheny Highlands. From the Author’s collection.

Every

so often, newspaper articles report that someone is killed when they build a

bonfire in a rock shelter3, so you must be careful if you build a

fire in a rock shelter.

Building

a fire in a rock shelter can be dangerous.

As your fire warms up the rock shelter and the rock of the ceiling, the

heat can cause the rock to expand, crack and collapse down onto you.

|

A simplified version of Figure 4-2, from “Prehistoric Rockshelters Of Pennsylvania: Revitalizing Behavioral Interpretation From Archaeological Spatial Data”, by Joseph Allen Burns, page 127. Note that the cooking and hearth use area are under the dashed line, which indicates the “dripline” of the shelter.

Always,

keep your fire at a safe distance from the roof of the overhang and the backwall,

by building your fire near the opening of the rock shelter. Look for the overhang’s dripline and build

your fire under it, just like the Native Americans who used these shelters

before the Euro-Americans came to these shores, did. In fact, archaeologists Dena Dincauze and R.

Michael Gramly, noted when writing about the Powisett Rock shelter in

Massachusetts that “...by situating the hearth toward the open side of the

rockshelter, the firebuilders in effect created half a small wigwam at the

site...This arrangement is the most efficient one possible in respect to smoke

dispersal, heat reflection...and the exclusion of outside drafts...”4. Dincauze and Gramly

weren’t the only archaeologists to notice that prehistoric and historic Native

Americans routinely placed their hearths under the dripline.

Doctoral

Candidate, Jonathan Allen Burns writing in “Prehistoric

Rockshelters Of Pennsylvania: Revitalizing Behavioral Interpretation From

Archaeological Spatial Data”, noted that while there is evidence for small

sleeping hearths in some shelters, the preponderance of sites and the evidence

shows that Native Americans usually put the main cooking hearth under the

dripline, particularly in the smaller rock shelters. He cited, as one example, W. Strohmeir, who

wrote “The Unami Creek Rockshelter”, in 1980, that the “greatest

concentration of charcoal and wood ash appeared beneath the drip line at the

front of the shelter” 5.

If our ancestors did it for thousands

of years, then maybe we should as well, today.

While

it is hard to determine this archaeologically, particularly in smaller rock

shelters, the rock free areas along the backwall offer the greatest protection

from the weather and make the best sleeping areas. Archaeologists and ethno-archaeologists have

suggested that these areas were used as sleeping areas by the Native Americans

and Euro-American travelers in the wilderness, during both the prehistoric and

historic eras.

|

Photograph taken November 23, 2016 in Minister Valley, in the Allegheny Highlands. From the Author’s collection.

|

Graphic by the author

Just

like in any survival shelter, you should always sit between your fire and the

back wall of the rock shelter, and you should always build a reflector. If you put the fire between you and the

backwall, your backside will be cold.

Instead, sit between your fire and the backwall of the rock shelter,

that way the heat from your fire will reflect off the backwall, warming up your

backside as well as your front. It will

also ensure that there is enough space between the fire and the roof and

backwall of the shelter, thereby reducing the chance of a cave-in or a roof

collapse.

As

an aside, the reflector will also help to channel the smoke upwards and away

from you. Also, always keep your fire

small and sit close to it. A big hot

bonfire wastes wood and you can’t sit near it, and in a rock shelter a large

fire can be dangerous, literally “bringing the roof down on you”.

I

hope you are never “misplaced” and have to overnight in a rock shelter like

this, but if you do I hope that you remember these tips and stay safe and warm

|

Graphic

by the Author.

|

Photograph taken November 12, 2017 in the Allegheny Highlands, from the Author’s collection.

Don’t forget to come back next week and read “Remember

This If You Want to be Warm ©”, where we will talk about how and why you should

always build a fire reflector, whenever you build a survival shelter.

I hope that you continue to enjoy The

Woodsman’s Journal Online and look for me on YouTube at Bandanaman Productions

for other related videos, HERE. Don’t

forget to follow me on both The Woodsman’s Journal Online, HERE, and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on

YouTube. If you have questions, as

always, feel free to leave a comment on either site. I announce new articles on Facebook at Eric

Reynolds, on Instagram at bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds,

so watch for me.

That is all for now, and as always, until next

time, Happy Trails!

Notes

1 For more information on my promise to you, the reader, read “The End

of 2018 and the Beginning of 2019 ©”, HERE

|

Figure 3-1, from “Prehistoric Rockshelters Of Pennsylvania: Revitalizing Behavioral Interpretation From Archaeological Spatial Data”, by Joseph Allen Burns, page 72.

A rock shelter is a sheltered space formed,

typically, from a rock ledge which has been carved out by flowing water or by

frost wedging of the freeze-thaw cycle and are formed where harder rock

overlays less-resistant rock. For more

information on how they are formed read “Rock Shelters or Half-Caves, That Home

Away From Home, Part One ©”, HERE.

3 Two recent newspaper articles which report on rock shelters and

campfires

November 24, 2015, “WHARTON, W.Va. - West Virginia State

Police say a hunter was killed after he and a fellow hunter built a fire and

the heat broke apart an overhanging boulder, tumbling on the hunter... the men had started the

fire under the boulder to seek heat.”

From AP, “W. Va. Hunter

killed in unusual campsite accident”

November 26, 2017, “With deer season nearly here, these

last-minute tips are key: ...Pick a spot for your fire where you have a

comfortable seat. Building the fire by a boulder will reflect more of the

warmth of the fire back to you. Deer hunters on the Allegheny Highlands have

long built fires at rock overhangs where they have good downhill views. At some

of these overhangs an astute observer may see signs of ancient hunters who

camped there.”

From Mike Bleech, “With deer season nearly

here, these last-minute tips are key”

4 This quote was originally printed in Dincauze, Dena F.;

and Gramly, R. Michael; “Powisett Rockshelter: Alternate Behavior Patterns in a

Simple Situation”, Pennsylvania Archaeologist, 1973, Journal 43, Volume 1,

pages 43-61.

From Elizabeth S. Chilton, “Archaeological

Investigations at the Goat Island Rockshelter: New Light from Old Legacies”,

page 16

5 Allen Joseph Burns, “Prehistoric Rockshelters Of Pennsylvania:

Revitalizing Behavioral Interpretation From Archaeological Spatial Data”

Sources

AP, “W. Va. Hunter

killed in unusual campsite accident”, November 24, 2015, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/west-virginia-hunter-killed-when-fire-breaks-apart-boulder-police-say/, accessed April 14,

2018

Bleech, Mike; “With deer

season nearly here, these last-minute tips are key”, Ellwood City Ledger, November

26, 2017, http://www.ellwoodcityledger.com/sports/20171126/mike-bleech-with-deer-season-nearly-here-these-last-minute-tips-are-key, April 5, 2018

Burns, Allen Joseph; “Prehistoric Rockshelters Of Pennsylvania:

Revitalizing Behavioral Interpretation From Archaeological Spatial Data”,

August, 2009, https://www.google.com/search?rlz=1C1OKWM_enUS921US921&ei=da6FX5vbD72JytMP0JCMkAM&q=rock+shelter+drip+line+hearth&oq=rock+shelter+drip+line+hearth&gs_lcp=CgZwc3ktYWIQAzIFCCEQoAE6BAgAEEc6BQghEKsCOggIIRAWEB0QHjoHCCEQChCgAVC9R1ipU2DiWGgAcAJ4AIABVogBxgOSAQE3mAEAoAEBqgEHZ3dzLXdpesgBBcABAQ&sclient=psy-ab&ved=0ahUKEwjb6ZKK2bHsAhW9hHIEHVAIAzIQ4dUDCA0&uact=5, page 72, accessed October 13, 2020

Chilton, Elizabeth S.; “Archaeological

Investigations at the Goat Island Rockshelter: New Light from Old Legacies”, http://www.hudsonrivervalley.org/review/pdfs/hvrr_9pt1_chilton.pdf, accessed April 9, 2018, page 16

Pinkerton, Paul; “Natural Shelters – Identifying And

Adapting A Survival Shelter”, Outdoor Revival, January 18, 2017 [© 2020 Outdoor

Revival], https://m.outdoorrevival.com/instant-articles/natural-shelters-identifying-and-adapting-a-survival-shelter.html, accessed November 2, 2020

Wildwood

Survival, “Caves”, [© by Walter Muma], http://www.wildwoodsurvival.com/survival/shelter/cave/index.html,

accessed November 2, 2020

No comments:

Post a Comment