Here is Part Two of the four parts series. It could have been titled “Stay Warm and Dry”. To read part one click HERE.–

Author’s Note.

|

In a winter survival situation, the most important thing to do is to stay as warm and dry as possible.

37oF

(3oC) with rain and gusty wind is vastly different from 0oF

(-18oC) with howling winds and whiteouts and so are the survival

challenges that you will need to overcome.

There is more than one type of winter environment, there is the “wet-cold”

climate and there is the “dry-cold”, and each has its own dangers. Depending on the region in which you are

forced to survive you might need to deal with one or the other, or both and

different days!

Wet-cold

climates are those in which the temperatures are always near freezing, and do

not normally falling below 14o F (-10o C). The ground will thaw during the day and will

turn to mud covered with slush and the snow will be wet, at night the ground

and the snow will refreeze. It can be

hard to stay dry under these conditions.

And dry-cold climates are those in which the temperatures are always

below freezing, and do not normally rise

above 14o F (-10o C).

The ground is always frozen, and the snow will be dry, day and night in

these areas.

How do you get cold?

Your

body loses heat through four processes, convection, conduction, radiation, and

evaporation.

Convection or

wind chill can cool you very quickly. Alan

E. Course, in The Best About Backpacking, wrote “a two-mile-an-hour

breeze can drag down body temperature as effectively as a twenty-mile gale if

the victim’s clothes are wet”. Your body

will lose between 10% to 15% of its heat through convection.

Conduction is

the loss of your body heat to the world around you, to the ground, if you are

sitting or sleeping on the snow or ground, to the air around you, or to water

if you are swimming or immersed in it. Body heat is lost to the air at temperatures

lower than 68°F (20°C), and your body will lose about 2% of its heat by air

conduction. However, you lose body heat

to water about 25 times faster than to the air, so you can lose body heat very

quickly if you are in cold water or wearing wet clothing.

Radiation is the process of

heat moving away from your body, like heat leaving a hot stove, and usually

occurs in air temperatures lower than 68°F (20°C). The body loses 65% of its heat through

radiation.

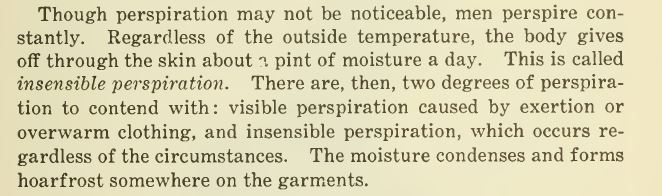

Evaporation

of water from your skin if you are sweating, or from your clothing if it is wet

will cool you. During heavy exercise,

your body will shed 85% of its heat by sweating. Also, you lose some body heat through

respiration (breathing). Heat loss by

evaporation and respiration will increase in dry or windy conditions.

How to stay warm...

|

Soldier’s Handbook for Individual Operations & Survival

in Cold Weather Areas TC 21-3, page 7. |

Dirty

clothes are cold clothes, because dirt and grease clog the insulating air

spaces and reduce your clothes overall ability to insulate you from the cold. In most survival situations today, you will

be rescued long before your inner and outer layers need to be cleaned, in

long-term survival situations, or if you get grease and oil on your outer

layers, that won’t be the case and you will need to wash them.

You

need to stay comfortably cold and as Les Stroud says, “If you sweat,

you die!” So, don’t

overexert and overheat. I you are

working up a sweat, remove some layers, before your clothes become damp.

|

An excerpt from the Polar Manual, page 149.

Comfortably

cold is when you are neither too warm nor too cold, you’re just right, maybe a

little bit cool, and you are not perspiring.

You can keep comfortably cold by reducing or increasing your activity

level as you become too hot or too cold.

But the best way to stay comfortably cold in the outdoors is by layering

your clothes, and by loosening, removing, or adding layers as you warm up or

cool down.

|

An excerpt from the Polar Manual, page 47.

For

more read “Comfortably Cold, What’s That?©”, HERE.

Layering your clothes, wicks

away sweat, adjusts insulation, and protects against wind, rain, and snow. It allows you to make quick adjustments based

on changes in the weather and your level of activity by adding or removing

layers. It is always better to

underdress and be too cool, than to overdress, be too hot.

There are three layers, and each layer has its own job.

· The

Base layer or

under layer is the most important as it is against your skin and keeps you dry,

it should of dry fast fabrics, like wool, synthetics, or

silk.

· The

Middle layer,

or insulating layer, helps you retain heat by trapping warmed air close to your

body and it should be made of wool, fleece or goose down.

· The

Outer layer is

sometimes also called, the shell layer, and it is the weather-proof layer or rain

gear.

|

An excerpt from the Polar Manual, page 30.

Also, make sure that each

layer is sized larger than the one under it so that the clothes fit loosely,

because tight clothes make it more likely that you will become cold or

frostbitten.

For

more on layering your clothes, read “The Top Ten Wilderness Survival

Skills...Number One ©”, HERE.

William

S. Carlson, an early Arctic explorer said that to “Keep dry is the first

rule of the North”1. That

means not sweating or not getting your clothes accidently wet.

|

An excerpt from Naval Arctic Operations Manual: Part 1 General Information, pages 161.

During

the winter, but any time really, you must stay dry to stay warm, because water will

cool you between 25 to 32 times faster than air2.

|

An excerpt from the Polar Manual, page 47.

If

you don’t stay warm and dry you can suffer frostbite, immersion foot or hypothermia,

and hypothermia, or exposure as it is also called, is one of the leading causes

of death in the wilderness!

What is Hypothermia...

|

From A Pocket Guide to Cold Water Survival, by the Coast Guard, page 7.

According to the USDA Forest Service,

“Hypothermia is the progressive mental and physical collapse that

accompanies the cooling of the inner core of the human body. It is caused by exposure to cold, is

aggravated by wet, wind, and exhaustion”3.

Hypothermia

is the lowering of your body’s core temperature to 95oF (35oC)

or below and is often caused by a combination of three factors, cold or quickly

changing temperatures, strong winds, or being wet, either from rain, sweat or

being immersed in cold water: it has three stages, mild, moderate, and severe.

· Mild

Hypothermia is when your core body temperature falls from 98.6o

(37oC) to between 95o and 90oF (35o

to 32oC). The symptoms of

mild hypothermia are intense, but controllable shivering and cold numb hands or

the “fumbles”3.

· Moderate

Hypothermia is when your core body temperature falls from 90o

to 86oF (32o to 30oC). The symptoms of moderate hypothermia are uncontrollable

shivering, confusion and movements that become slow and labored, and slurred

speech -- look for the “stumbles”, the “mumbles”, and the “grumbles”.

· Severe

Hypothermia is when your core body temperature drops to between

86o and 78oF (30o to 25oC). The symptoms are extremely cold skin,

sleepiness or unconsciousness and a pulse that is irregular or difficult to

find.

For

more read “Hypothermia, It Can Happen Any Time, Anywhere ©”, HERE.

What is immersion foot?

|

A mild case of immersion foot or as it is also known “trench foot”, from Wikimedia HERE.

In

the winter, wet feet and hands are frozen feet and hands, and frozen feet and

hands spell disaster! Even if it isn’t

below freezing, wet feet or hands can lead to “immersion-foot”, which is

also known, “trench foot”, is a non-freezing cold injury (NFCI), that can

happen either the hands or feet, but often affects the feet. It is caused by long exposure to wet, cold,

but not necessarily freezing conditions, with temperatures of 32 to 59°F (0 to 15°C)4.

In

the winter, wet feet and hands are frozen feet and hands, and frozen feet and

hands spell disaster! Even if it isn’t

below freezing, wet feet or hands can lead to “immersion-foot”, which is

also known, “trench foot”, is a non-freezing cold injury (NFCI), that can

happen either the hands or feet, but often affects the feet. It is caused by long exposure to wet, cold,

but not necessarily freezing conditions, with temperatures of 32 to 59°F (0 to 15°C)4.

Like

any cold injury, it is aggravated by wind and windchill, when wet boots or

gloves and evaporation combine to cool the surface of your hands, feet, and

ankles. This cooling causes the body to

shut-off the blood flow to the skin surface and to the tissue just below the

skin of your hands, feet, and ankles, causing them to look white, waxy, and

dead. If untreated, immersion foot can

lead to serious and painful complications, such as gangrene.

Survivors

of accidents and others who are exposed to cold, wet conditions for days

without removing wet boots and socks or gloves risk immersion foot.

For

more about immersion foot, read “Accidental Lessons … Boots Freeze!©”, HERE

and “Survival Tips From Jack London, Part One©”, HERE.

What is frostbite?

|

Mountaineer Nigel Vardy being treated for frostbite, from Wikimedia, HERE.

Watch

out for frostbite, which will appear as a wooden or waxy, gray, or white patch. It most commonly occurs on the hands, feet,

nose, cheeks, forehead, and ears. Frostbite

results from the freezing of exposed skin and is a disabling injury but is not

likely to be fatal.5

Four Tips for keeping the heat in

Tip 1: Huddle close with the other survivors to share body heat. Keep your huddle always moving because moving will keep you warm. If you have no warm clothing or gloves, claps hands energetically once an hour. If you are by yourself, exercise by tensing and relaxing your muscles, this will also keep your body warm and the blood circulating throughout your body.

Tip 2: The loss of heat from your body depends on the air temperature and the square of the wind speed and is called windchill. So, stay OUT of the wind, and avoid windchill. Windchill makes already cold temperatures FEEL even colder, because the wind steals away your body heat through convection. When there is little to no wind, a layer of warm remains around your body to help you stay warm. When it's windy, or breezy, the moving air blows away that insulating, warm layer, quickening your heat loss, and making you feel colder.

So,

ALWAYS shelter from the wind!

Tip 3: Preventing frostbite and immersion foot is easier than treating it.

To

check for frostbite, wrinkle your face, wriggle your toes, and clench your

hands, if it feels like there are stiff patches, it might be frostbite.

|

An excerpt from Arctic Survival PAM (Air) 226, by the Air Ministry, 1953.

Remember

if it hurts, it isn’t frozen, because frozen patches have no feeling, however

this doesn’t mean you should ignore the situation.

To

treat frostbite on your face, warm it with an un-mittened hand; for frostbitten

hands slide the un-mittened hand inside your shirt against your skin; for

frostbitten feet, take off your boots and socks, and slide your feet up inside

your partner’s shirt against their skin.

|

An excerpt from Naval Arctic Operations, page 167.

To

prevent immersion foot, keep your circulation moving to your hands and feet, by

clapping your hands, stomping your feet, moving around, and staying dry.

|

An excerpt from Army Talks, Vol. III, No. 5, February 10, 1945.

To

treat immersion foot, to either the feet or the hands, if your socks or gloves

get wet, change into dry ones as soon as possible. Also, have a set routine to dry, warm,

massage and inspect your hands and feet daily.

|

An excerpt from Army Talks, Vol. III, No. 5, February 10, 1945.

Tip 4: Put on a hat, since heat loss from your bare head can be up to 33% at 60oF (15oC), up to 50% at 40oF (4oC) and up to 75% at 5oF (-15oC)6. And keep your hands and feet dry and warm.

|

An excerpt from the Polar Manual, page 37.

Wear

mittens or gloves and protect your hands, because if your hands freeze or are

injured, you are helpless, and survival becomes very difficult. And don’t forget your feet, being disabled in

the wilderness is remedy for disaster.

Tip 5: Protect your eyes from snow blindness. Snow blindness, or photokeratitis, is caused by UV rays sunburning the corneas of your eyes. It is very painful, and is often experienced snowfields, particularly at high altitudes. So, be prepared and always have a pair of with retaining straps. In an emergency, if you don’t have a pair UV rated, wrap-around sunglasses, you could blacken your cheekbones and your face below your eyes with Chapstick© or Vaseline® mixed with charcoal to reduce glare and the UV rays reflecting into your eyes. You could also tie a bandanna or piece of cloth, with eye slits cut into it, over your eyes, when possible, choose a dark colored bandana or piece of cloth. You could even fold a piece of duct tape back over itself and cut eye slits into to make a pair of Inuit style snow goggles.

|

An excerpt from Arctic Survival PAM (Air) 226, by the Air Ministry, 1953, page 54.

|

“Make Your Own Snow Goggles!”, by the Bowdoin Arctic Museum, HERE.

|

Beware of snow blindness, An excerpt from the Polar Manual, 1953, page 67.

For

more on making “slit goggles”, read “The Survival Uses of Aluminum Foil ©, HERE.

Tip 6: To stay dry, don’t sit in the snow and ALWAYS brush off any snow or ice from your clothes, before entering a shelter or approaching a fire.

|

An excerpt from Arctic Survival PAM (Air) 226, by the Air Ministry, 1953, page 57.

Don’t forget to come back next week and read “Winter Survival for

Tommy...Part Three©”, where we will talk about improvising for survival, using

plane parts, calling for help and signaling for rescue.

I

hope that you continue to enjoy The Woodsman’s Journal Online and look for me

on YouTube at BandanaMan Productions for other related videos, HERE. Don’t forget to follow me on both The Woodsman’s

Journal Online, HERE,

and subscribe to BandanaMan Productions on YouTube. If you have questions, as always, feel free

to leave a comment on either site. I

announce new articles on Facebook at Eric Reynolds, on Instagram at

bandanamanaproductions, and on VK at Eric Reynolds, so watch for me.

That

is all for now, and as always, until next time, Happy Trails!

Notes

1

From Naval Arctic Operations Manual: Part 1 General Information, p. 157

2 Wilderness

Survival states that the heat loss is 32 times and A Pocket Guide to

Cold Water Survival says that the heat loss from being wet is 25 times that

of when you are dry.

From

Wilderness Survival, by Ministry of Forests, page 46; and A Pocket

Guide to Cold Water Survival, by Coast Guard, Department of Transportation,

page 12.

3

USDA Forest Service, “Exposure/Hypothermia”

4 “Nonfreezing cold water (trench foot) and warm water

immersion injuries”, by Ken Zafren, MD, FAAEM, FACEP, FAWM

5“Frostbite:

Emergency care and prevention”, by Ken Zafren, MD, FAAEM, FACEP, FAWM

6 Polar

Manual, Fourth Edition, by Captain Earland E. Hedblom, MC, USN, page 37

Sources

Air

Safety Institute, AOPA; “Survive: Beyond the Forced Landing”,

[Frederick, Maryland], http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=57&ved=0ahUKEwjjpoab-eTYAhWMp5QKHYYIA0o4MhAWCEswBg&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.aopa.org%2F-%2Fmedia%2Ffiles%2Faopa%2Fhome%2Fpilot%2520resources%2Fasi%2Fsafety%2520advisors%2Fsa31.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0MXBFxEgfsS5ow6y80vbbv, accessed September 1, 2021

Airscoop; “Winter

Survival”, Approach, Jan 1974, Volume 19, Issue 7, page 12 – 14, https://books.google.com/books?id=CJlUaA0_rtMC&pg=PP14&dq=snow+survival&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwimj8jA-Lb8AhU0MVkFHY-YBG8Q6AF6BAgHEAI#v=onepage&q=snow%20survival&f=false,

accessed January 10, 2023

American Council on

Exercise; “Fit Facts: Exercising in the Cold”, [©American Council on Exercise],

https://acewebcontent.azureedge.net/assets/education-resources/lifestyle/fitfacts/pdfs/fitfacts/itemid_24.pdf,

accessed January 12, 2023

Black,

Marina; and Jonescu, Kaitlyn; “How to Survive a Plane Crash in the Arctic”, May

20, 2014, [© 2023 Prezi Inc], https://prezi.com/ceo1kdavlin0/how-to-survive-a-plane-crash-in-the-arctic/,

accessed January 12, 2023

Calvert,

John H., Jr. Colonel; “Frostbite”, Flying Safety, October 1992, Publication

127-2, Vol. 48, No. 10, [United States Airforce, 1992], pages 14 - 15, https://books.google.com/books?id=W2PU4Rad3JMC&pg=RA21-PA26&dq=survival+pamphlet&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwim-sLv-cT8AhWMKFkFHf9FA184PBDoAXoECAkQAg#v=onepage&q=survival%20pamphlet&f=false, accessed January 13, 2023

Coast

Guard, Department of Transportation, A Pocket Guide to Cold Water Survival,

CG

473, September 1975, https://books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5QafxNJBmiIml6O4jiudRpr2rz8pLfodQOiq-4gZNh4xa5uIN_rq05C2yAes1AYw67Ziq189QaQaFDHBHE0SJivfCxjMW1DReANLjFqw1qX6jEl2mz1HPKXj4BRQJv8zAOcO6oDE70Dcv__VE2uPh4tEqLSzMxDRiWOv3p6ssyQjE2bevJMX7-Ol2KDtIPQVcVuaJudJMLaOOuSUVs8qYS1Nlaxnm47GVOCXLR79KzL6nV3R0zZG4DxRt9hoYrIRGugXm6RVfbU2gxeix7JLKbxpvQsNB9w,

accessed May 1, 2022

Combat Crew Training

Wing; “Obtaining Water”, Flying Safety, October 1992, Publication 127-2,

Vol. 48, No. 10, [United States Airforce, 1992], pages 26, https://books.google.com/books?id=W2PU4Rad3JMC&pg=RA21-PA26&dq=survival+pamphlet&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwim-sLv-cT8AhWMKFkFHf9FA184PBDoAXoECAkQAg#v=onepage&q=survival%20pamphlet&f=false,

accessed January 13, 2023

Defense

Mapping Agency; Sailing Directions (Planning Guide) for the Arctic Ocean,

First Edition, [Defense Mapping Agency Hydrographic/Topographic Agency,

1983], page 286 - 293, https://books.google.com/books?id=dpUn0tHp7VMC&pg=PA291&dq=winter+survival+melting+snow+for+water&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjVjZ2T86n8AhUEp3IEHcZyAvY4KBDoAXoECAUQAg#v=onepage&q=winter%20survival%20melting%20snow%20for%20water&f=false,

accessed January 10, 2023

Federal Aviation

Administration; “At Home in The Snow”, FAA General Aviation News ,

November-December, 1983,Volume 22, Issue 6, page 11 – 12, https://books.google.com/books?id=BWX3xkpPHFUC&pg=PA11&dq=crashed+plane+winter&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjHn4jlr8D8AhXMGVkFHYOiCYcQ6AF6BAgIEAI#v=onepage&q=crashed%20plane%20winter&f=false,

accessed January 13, 2023

Federal Aviation Administration;

Basic Survival Skills for Aviation, [FAA, Oklahoma City, OK], page

44-51, https://www.faa.gov/pilots/training/airman_education/media/CAMISurvivalManual.pdf,

accessed January 12, 2023

Federal Aviation

Administration; “Post Crash Survival”, FAA General Aviation News ,

November-December, 1979,Volume 22, Issue 6, page 8 – 10, https://books.google.com/books?id=Y0YPi63uDIcC&pg=RA5-PA8&dq=survival+snow&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiu8IfVu7n8AhW8EVkFHfW2BbY4MhDoAXoECAcQAg#v=onepage&q=survival%20snow&f=false,

Accessed January 10, 2023

Hedblom,

Captain Earland E. MC, USN; Polar Manual, Fourth Edition, [National

Naval Medical Center, Bethesda, MD, 1965], p. 37, https://ia800305.us.archive.org/33/items/PolarManual4thEd1965/Polar%20Manual%204th%20ed%20%281965%29.pdf,

accessed 12/07/2019

Ministry

of Forests, Wilderness Survival, [Ministry of Forests, British Columbia,

1978], p. 46

Nelson,

Morlan W.; “Cold Weather Survival”, Popular Science, November 1971, pages

123-126, https://books.google.com/books?id=PQEAAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA123&dq=snow+survival&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwimj8jA-Lb8AhU0MVkFHY-YBG8Q6AF6BAgGEAI#v=onepage&q=snow%20survival&f=false,

accessed January 12, 2023

Pinkerton,

Paul; “Surviving A Plane Crash Pt3 – Using aircraft parts in survival”,

December 16, 2016, [© 2023 Outdoor Revival], https://www.outdoorrevival.com/instant-articles/surviving-plane-crash-pt3-using-aircraft-parts-survival.html,

accessed January 12, 2023

Schul,

Dorothy; “Trapped in Hell’s Canyon”, Flying Safety, October 1992, Publication

127-2, Vol. 48, No. 10, [United States Airforce, 1992], pages 2 - 6, https://books.google.com/books?id=W2PU4Rad3JMC&pg=RA21-PA26&dq=survival+pamphlet&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwim-sLv-cT8AhWMKFkFHf9FA184PBDoAXoECAkQAg#v=onepage&q=survival%20pamphlet&f=false, accessed January 13, 2023

The Air Ministry, Arctic

Survival PAM (Air) 226, 1953, https://ia801909.us.archive.org/2/items/ArcticSurvival/Arctic%20Survival%20and%20Jungle%20Survival%20combined.pdf,

accessed January 12, 2023

USDA Forest Service, “Exposure/Hypothermia”,

https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/r3/recreation/safety-ethics/?cid=fsbdev3_021634#:~:text=Hypothermia%20may%20be%20a%20new,wet%2C%20wind%2C%20and%20exhaustion,

accessed January 20, 2023

United States, Department of the Army; Soldier’s Handbook for Individual Operations &

Survival in Cold Weather Areas TC 21-3, [Headquarters, Department of

the Army, September 1974, https://books.google.com/books?id=5VssAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA105&dq=survive+hunter&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjA9Yehlc38AhXlFlkFHWuGAtI4PBDoAXoECAYQAg#v=onepage&q=survive%20hunter&f=false,

accessed January 10, 2023

United States, Department of the Air Force; Survival

Training Edition, AF Manual 64-3, [Air Training Command, U.S. Government

Printing Office, Washington, D.C., August 15, 1969], page 2-7

to 2-10

United States Army, “Baby

Your Feet”, Army Talks, Vol. III, No. 5,

February 10, 1945, page 7-9, 18, http://www.90thidpg.us/Reference/Army%20Talks/foxhole.pdf,

accessed January 18, 2023

United States, Department of the Navy; Naval Arctic

Operations Manual: Part 1 General Information, [Department of the Navy, 1949,

Revised in 1950], p. 157-175,

https://ia600301.us.archive.org/27/items/navalarcticopera00unit/navalarcticopera00unit.pdf, accessed August 28, 2018

United

States Marine Corps; Winter Survival Course Handbook, 2002, [Mountain Warfare

Training Center, Bridgeport, CA, 2002], https://ia802602.us.archive.org/22/items/milmanual-us-marine-corps---mwtc-winter-survival-course-handbook/us_marine_corps_-_mwtc_winter_survival_course_handbook.pdf,

accessed January 9, 2023

Way.com;

“6.5 Million Cars Are Catching Fire – Is Yours One of Them?”, [© 2023 WAY.COM],

https://www.way.com/blog/millions-of-cars-are-catching-fire-is-yours-one-of-them/#:~:text=How%20often%20do%20cars%20catch,according%20to%20the%20NFPA's%20statistics,

accessed January 9, 2023

Zafren, Ken, MD, FAAEM,

FACEP, FAWM; “Nonfreezing cold water (trench foot) and warm water immersion

injuries”, UpToDate®, October 26, 2022, https://www.uptodate.com/contents/nonfreezing-cold-water-trench-foot-and-warm-water-immersion-injuries,

accessed January 20, 2023

Zafren, Ken, MD, FAAEM,

FACEP, FAWM; “Frostbite: Emergency care and prevention”,

UpToDate®, May 26, 2022, https://www.uptodate.com/contents/frostbite-emergency-care-and-prevention?topicRef=13789&source=see_link,

accessed January 20, 2023

Zafren, Ken, MD, FAAEM,

FACEP, FAWM; “Accidental hypothermia in adults”, UpToDate®, January 12, 2023 https://www.uptodate.com/contents/accidental-hypothermia-in-adults?topicRef=179&source=see_link,

accessed January 20, 2023

No comments:

Post a Comment